Applied Framework Illustration – Barnard (1991) Bridging between Basic Theories and the Artifacts of Human-Computer Interaction

Bridging between Basic Theories and the Artifacts of Human-Computer Interaction

Phil Barnard

In: Carroll, J.M. (Ed.). Designing Interaction: psychology at the human-computer interface.

New York: Cambridge University Press, Chapter 7, 103-127. This is not an exact copy of paper

as it appeared but a DTP lookalike with very slight differences in pagination.

Psychological ideas on a particular set of topics go through something very much

like a product life cycle. An idea or vision is initiated, developed, and

communicated. It may then be exploited, to a greater or lesser extent, within the

research community. During the process of exploitation, the ideas are likely to

be the subject of critical evaluation, modification, or extension. With

developments in basic psychology, the success or penetration of the scientific

product can be evaluated academically by the twin criteria of citation counts and

endurance. As the process of exploitation matures, the idea or vision stimulates

little new research either because its resources are effectively exhausted or

because other ideas or visions that incorporate little from earlier conceptual

frameworks have taken over. At the end of their life cycle, most ideas are

destined to become fossilized under the pressure of successive layers of journals

opened only out of the behavioral equivalent of paleontological interest.

In applied domains, research ideas are initiated, developed, communicated,

and exploited in a similar manner within the research community. Yet, by the

very nature of the enterprise, citation counts and endurance are of largely

academic interest unless ideas or knowledge can effectively be transferred from

research to development communities and then have a very real practical impact

on the final attributes of a successful product.

Comment 1The transfer of research to development communities here constitutes the very idea of Applied Psychology.

If we take the past 20-odd years as representing the first life cycle of research

in human-computer interaction, the field started out with few empirical facts and

virtually no applicable theory. During this period a substantial body of work

was motivated by the vision of an applied science based upon firm theoretical

foundations.

Comment 2The primary applied science in the case of HCI is Psychology, although this does not exclude others, for example, Sociology, Ethnomethodology etc.

As the area was developed, there can be little doubt, on the twin

academic criteria of endurance and citation, that some theoretical concepts have

been successfully exploited within the research community. GOMS, of course,

is the most notable example (Card, Moran, & Newell, 1983; Olson & Olson,

1990; Polson, 1987).

Comment 3These examples contain lower-level descriptions of applied frameworks for HCI, some woth and some without overlaps.

Yet, as Carroll (e.g., l989a,b) and others have pointed

out, there are very few examples where substantive theory per se has had a major

and direct impact on design. On this last practical criterion, cognitive science can

more readily provide examples of impact through the application of empirical

methodologies and the data they provide and through the direct application of

psychological reasoning in the invention and demonstration of design concepts

(e.g., see Anderson & Skwarecki, 1986; Card & Henderson, 1987; Carroll,

1989a,b; Hammond & Allinson, 1988; Landauer, 1987).

Comment 4The application of empirical methodologies and the data of Applied Psychology have also contributed to the development of HCI research and practice.

As this research life cycle in HCI matures, fundamental questions are being

asked about whether or not simple deductions based on theory have any value at

all in design (e.g. Carroll, this volume), or whether behavior in human-computer

interactions is simply too complex for basic theory to have anything other than a

minor practical impact (e.g., see Landauer, this volume). As the next cycle of

research develops, the vision of a strong theoretical input to design runs the risk

of becoming increasingly marginalized or of becoming another fossilized

laboratory curiosity. Making use of a framework for understanding different

research paradigms in HCI, this chapter will discuss how theory-based research

might usefully evolve to enhance its prospects for both adequacy and impact.

Bridging Representations

In its full multidisciplinary context, work on HCI is not a unitary enterprise.

Rather, it consists of many different sorts of design, development, and research

activities. Long (1989) provides an analytic structure through which we can

characterize these activities in terms of the nature of their underlying concepts

and how different types of concept are manipulated and interrelated. Such a

framework is potentially valuable because it facilitates specification of,

comparison between, and evaluation of the many different paradigms and

practices operating within the broader field of HCI.

With respect to the relationship between basic science and its application,

Comment 5This relationship is the nub of Application Framework Illustration presented in this paper.

Long makes three points that are fundamental to the arguments to be pursued in

this and subsequent sections. First, he emphasizes that the kind of

understanding embodied in our science base is a representation of the way in

which the real world behaves. Second, any representation in the science base

can only be mapped to and from the real world by what he called “intermediary”

representations. Third, the representations and mappings needed to realize this

kind of two-way conceptual traffic are dependent upon the nature of the activities

they are required to support. So the representations called upon for the purposes

of software engineering will differ from the representations called upon for the

purposes of developing an applicable cognitive theory.

Comment 6Applicable Cognitive Theory here is the basic science and Software Engineering the object of its application. See also Comments 2 and 4.

Long’s framework is itself a developing one (1987, 1989; Long & Dowell,

1989). Here, there is no need to pursue the details; it is sufficient to emphasize

that the full characterization of paradigms operating directly with artifact design

differs from those characterizing types of engineering support research, which,

in turn, differ from more basic research paradigms.

Comment 7Basic (Psychology) research and artifact (interactive system) design and their relationship is of the primary concern here.

This chapter will primarily

be concerned with what might need to be done to facilitate the applicability and

impact of basic cognitive theory.

Comment 8

The need to facilitate the applicability and impact of basic cognitive theory on artifact design suggests its current applicability is unacceptable.

In doing so it will be argued that a key role

needs to be played by explicit “bridging” representations. This term will be used

to avoid any possible conflict with the precise properties of Long’s particular

conceptualization.

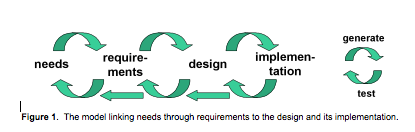

Following Long (1989), Figure 7.1 shows a simplified characterization of an

applied science paradigm for bridging from the real world of behavior to the

science base and from these representations back to the real world.

Comment 9Long’s framework is itself an applied framework.

The blocks are intended to characterize different sorts of representation and the arrows stand

for mappings between them (Long’s terminology is not always used here). The

real world of the use of interactive software is characterized by organisational,

group, and physical settings; by artifacts such as computers, software, and

manuals; by the real tasks of work; by characteristics of the user population; and

so on. In both applied and basic research, we construct our science not from the

real world itself but via a bridging representation whose purpose is to support

and elaborate the process of scientific discovery.

Comment 10Lower-level descriptions of the Applied Framework are to be found in the different representations referenced here.

Obviously, the different disciplines that contribute to HCI each have their

own forms of discovery representation that reflect their paradigmatic

perspectives, the existing contents of their science base, and the target form of

their theory. In all cases the discovery representation incorporates a whole range

of explicit, and more frequently implicit, assumptions about the real world and

methodologies that might best support the mechanics of scientific abstraction. In

the case of standard paradigms of basic psychology, the initial process of

analysis leading to the formation of a discovery representation may be a simple

observation of behavior on some task. For example, it may be noted that

ordinary people have difficulty with particular forms of syllogistic reasoning. In

more applied research, the initial process of analysis may involve much more

elaborate taxonomization of tasks (e.g., Brooks, this volume) or of errors

observed in the actual use of interactive software (e.g., Hammond, Long, Clark,

Barnard, & Morton, 1980).

Conventionally, a discovery representation drastically simplifies the real

world. For the purposes of gathering data about the potential phenomena, a

limited number of contrastive concepts may need to be defined, appropriate

materials generated, tasks selected, observational or experimental designs

determined, populations and metrics selected, and so on. The real world of

preparing a range of memos, letters, and reports for colleagues to consider

before a meeting may thus be represented for the purposes of initial discovery by

an observational paradigm with a small population of novices carrying out a

limited range of tasks with a particular word processor (e.g., Mack, Lewis, &

Carroll, 1983). In an experimental paradigm, it might be represented

noninteractively by a paired associate learning task in which the mappings

between names and operations need to be learned to some criterion and

subsequently recalled (e.g., Scapin, 1981). Alternatively, it might be

represented by a simple proverb-editing task carried out on two alternative

versions of a cut-down interactive text editor with ten commands. After some

form of instructional familiarization appropriate to a population of computernaive

members of a Cambridge volunteer subject panel, these commands may be

used an equal number of times with performance assessed by time on task,

errors, and help usage (e.g., Barnard, Hammond, MacLean, & Morton, 1982).

Each of the decisions made contributes to the operational discovery

representation.

Comment 11Note that the operationalisation of basic Psychology theory for the purposes of design is not the same as the operational discovery representation of that theory.

The resulting characterizations of empirical phenomena are potential

regularities of behavior that become, through a process of assimilation,

incorporated into the science base where they can be operated on, or argued

about, in terms of the more abstract, interpretive constructs. The discovery

representations constrain the scope of what is assimilated to the science base and

all subsequent mappings from it.

Comment 12Note that the scope of the science base and the scope of the applied base can be the same, although the purposes (and so the knowledge) differ.

The conventional view of applied science also implies an inverse process

involving some form of application bridge whose function is to support the

transfer of knowledge in the science base into some domain of application.

Classic ergonomics-human factors relied on the handbook of guidelines. The

relevant processes involve contextualizing phenomena and scientific principles

for some applications domain – such as computer interfaces, telecommunications

apparatus, military hardware, and so on. Once explicitly formulated, say in

terms of design principles, examples and pointers to relevant data, it is left up to

the developers to operate on the representation to synthesize that information

with any other considerations they may have in the course of taking design

decisions. The dominant vision of the first life cycle of HCI research was that

this bridging could effectively be achieved in a harder form through engineering

approximations derived from theory (Card et al., 1983). This vision essentially

conforms to the full structure of Figure 7.1

The Chasm to Be Bridged

The difficulties of generating a science base for HCI that will support effective

bridging to artifact design are undeniably real. Many of the strategic problems

theoretical approaches must overcome have now been thoroughly aired. The life

cycle of theoretical enquiry and synthesis typically postdates the life cycle of

products with which it seeks to deal; the theories are too low level; they are of

restricted scope; as abstractions from behavior they fail to deal with the real

context of work and they fail to accommodate fine details of implementations and

interactions that may crucially influence the use of a system (see, e.g.,

discussions by Carroll & Campbell, 1986; Newell & Card, 1985; Whiteside &

Wixon, 1987). Similarly, although theory may predict significant effects and

receive empirical support, those effects may be of marginal practical consequence

in the context of a broader interaction or less important than effects not

specifically addressed (e.g., Landauer, 1987).

Our current ability to construct effective bridges across the chasm that

separates our scientific understanding and the real world of user behavior and

artifact design clearly falls well short of requirements. In its relatively short

history, the scope of HCI research on interfaces has been extended from early

concerns with the usability of hardware, through cognitive consequences of

software interfaces, to encompass organizational issues (e.g., Grudin, 1990).

Against this background, what is required is something that might carry a

volume of traffic equivalent to an eight-lane cognitive highway. What is on offer

is more akin to a unidirectional walkway constructed from a few strands of rope

and some planks.

In Taking artifacts seriously Carroll (1989a) and Carroll, Kellogg, and

Rosson in this volume, mount an impressive case against the conventional view

of the deductive application of science in the invention, design, and development

of practical artifacts. They point both to the inadequacies of current informationprocessing

psychology, to the absence of real historical justification for

deductive bridging in artifact development, and to the paradigm of craft skill in

which knowledge and understanding are directly embodied in artifacts.

Likewise, Landauer (this volume) foresees an equally dismal future for theory-based

design.

Whereas Landauer stresses the potential advances that may be achieved

through empirical modeling and formative evaluation. Carroll and his colleagues

have sought a more substantial adjustment to conventional scientific strategy

(Carroll, 1989a,b, 1990; Carroll & Campbell, 1989; Carroll & Kellogg, 1989;

Carroll et al., this volume). On the one hand they argue that true “deductive”

bridging from theory to application is not only rare, but when it does occur, it

tends to be underdetermined, dubious, and vague. On the other hand they argue

that the form of hermaneutics offered as an alternative by, for example,

Whiteside and Wixon (1987) cannot be systematized for lasting value. From

Carroll’s viewpoint, HCI is best seen as a design science in which theory and

artifact are in some sense merged. By embodying a set of interrelated

psychological claims concerning a product like HyperCard or the Training

Wheels interface (e.g., see Carroll & Kellogg, 1989), the artifacts themselves

take on a theorylike role in which successive cycles of task analysis,

interpretation, and artifact development enable design-oriented assumptions

about usability to be tested and extended.

This viewpoint has a number of inviting features. It offers the potential of

directly addressing the problem of complexity and integration because it is

intended to enable multiple theoretical claims to be dealt with as a system

bounded by the full artifact. Within the cycle of task analysis and artifact

development, the analyses, interpretations, and theoretical claims are intimately

bound to design problems and to the world of “real” behavior. In this context,

knowledge from HCI research no longer needs to be transferred from research

into design in quite the same sense as before and the life cycle of theories should

also be synchronized with the products they need to impact. Within this

framework, the operational discovery representation is effectively the rationale

governing the design of an artifact, whereas the application representation is a

series of user-interaction scenarios (Carroll, 1990).

The kind of information flow around the task – artifact cycle nevertheless

leaves somewhat unclear the precise relationships that might hold between the

explicit theories of the science base and the kind of implicit theories embodied in

artifacts. Early on in the development of these ideas, Carroll (1989a) points out

that such implicit theories may be a provisional medium for HCI, to be put aside

when explicit theory catches up. In a stronger version of the analysis, artifacts

are in principle irreducible to a standard scientific medium such as explicit

theories. Later it is noted that “it may be simplistic to imagine deductive relations

between science and design, but it would be bizarre if there were no relation at

all” (Carroll & Kellogg, 1989). Most recently, Carroll (1990) explicitly

identifies the psychology of tasks as the relevant science base for the form of

analysis that occurs within the task-artifact cycle (e.g. see Greif, this volume;

Norman this volume). The task-artifact cycle is presumed not only to draw upon

and contextualize knowledge in that science base, but also to provide new

knowledge to assimilate to it. In this latter respect, the current view of the task

artifact cycle appears broadly to conform with Figure 7.1. In doing so it makes

use of task-oriented theoretical apparatus rather than standard cognitive theory

and novel bridging representations for the purposes of understanding extant

interfaces (design rationale) and for the purposes of engineering new ones

(interaction scenarios).

In actual practice, whether the pertinent theory and methodology is grounded

in tasks, human information-processing psychology or artificial intelligence,

those disciplines that make up the relevant science bases for HCI are all

underdeveloped. Many of the basic theoretical claims are really provisional

claims; they may retain a verbal character (to be put aside when a more explicit

theory arrives), and even if fully explicit, the claims rarely generalize far beyond

the specific empirical settings that gave rise to them. In this respect, the wider

problem of how we go about bridging to and from a relevant science base

remains a long-term issue that is hard to leave unaddressed. Equally, any

research viewpoint that seeks to maintain a productive role for the science base in

artifact design needs to be accompanied by a serious reexamination of the

bridging representations used in theory development and in their application.

Science and design are very different activities. Given Figure 7.1., theorybased

design can never be direct; the full bridge must involve a transformation of

information in the science base to yield an applications representation, and

information in this structure must be synthesized into the design problem. In

much the same way that the application representation is constructed to support

design, our science base, and any mappings from it, could be better constructed

to support the development of effective application bridging. The model for

relating science to design is indirect, involving theoretical support for

Basic Theories and the Artifacts of HCI 109

engineering representations (both discovery and applications) rather than one

involving direct theoretical support in design.

The Science Base and Its Application

In spite of the difficulties, the fundamental case for the application of cognitive

theory to the design of technology remains very much what it was 20 years ago,

and indeed what it was 30 years ago (e.g., Broadbent, 1958). Knowledge

assimilated to the science base and synthesized into models or theories should

reduce our reliance on purely empirical evaluations. It offers the prospect of

supporting a deeper understanding of design issues and how to resolve them.

Comment 13Note that the (Psychology) science base in the form of Cognitive Theory seeks both understanding of human-computer interaction design issues (presumably as explanation of known phenomena and the prediction of unknown phenomena) and the resolution of design problems.

Indeed, Carroll and Kellogg’s (1989) theory nexus has developed out of a

cognitive paradigm rather than a behaviorist one. Although theory development

lags behind the design of artifacts, it may well be that the science base has more

to gain than the artifacts. The interaction of science and design nevertheless

should be a two-way process of added value.

Comment 14Hence the requirement for both a science and an applied framework for HCI. The former seeks to understand the phenomena, associated with humans interacting with computers,while the later seeks to support the design of human-computer interactions.

Much basic theoretical work involves the application of only partially explicit

and incomplete apparatus to specific laboratory tasks. It is not unreasonable to

argue that our basic cognitive theory tends only to be successful for modeling a

particular application. That application is itself behavior in laboratory tasks. The

scope of the application is delimited by the empirical paradigms and the artifacts

it requires – more often than not these days, computers and software for

presentation of information and response capture. Indeed, Carroll’s task-artifact

and interpretation cycles could very well be used to provide a neat description of

the research activities involved in the iterative design and development of basic

theory. The trouble is that the paradigms of basic psychological research, and

the bridging representations used to develop and validate theory, typically

involve unusually simple and often highly repetitive behavioral requirements

atypical of those faced outside the laboratory.

Comment 15Note that the validation of basic psychological theory does not of itself guarantee its successful resolution of design problems. See also Comment 14.

Although it is clear that there are many cases of invention and craft where the

kinds of scientific understanding established in the laboratory play little or no

role in artifact development (Carroll, 1989b), this is only one side of the story.

Comment 16Hence the need here for separate frameworks for both Innovation (as invention) and Craft. See the relevant framework sections.

The other side is that we should only expect to find effective bridging when what

is in the science base is an adequate representation of some aspect of the real

world that is relevant to the specific artifact under development. In this context it

is worth considering a couple of examples not usually called into play in the HCI

domain.

Psychoacoustic models of human hearing are well developed. Auditory

warning systems on older generations of aircraft are notoriously loud and

unreliable. Pilots don’t believe them and turn them off. Using standard

techniques, it is possible to measure the noise characteristics of the environment

on the flight deck of a particular aircraft and to design a candidate set of warnings

based on a model of the characteristics of human hearing. This determines

whether or not pilots can be expected to “hear” and identify those warnings over

the pattern of background noise without being positively deafened and distracted

(e.g., Patterson, 1983). Of course, the attention-getting and discriminative

properties of members of the full set of warnings still have to be crafted. Once

established, the extension of the basic techniques to warning systems in hospital

intensive-care units (Patterson, Edworthy, Shailer, Lower, & Wheeler, 1986)

and trains (Patterson, Cosgrove, Milroy, & Lower, 1989) is a relatively routine

matter.

Developed further and automated, the same kind of psychoacoustic model

can play a direct role in invention. As the front end to a connectionist speech

recognizer, it offers the prospect of a theoretically motivated coding structure that

could well prove to outperform existing technologies (e.g., see ACTS, 1989).

As used in invention, what is being embodied in the recognition artifact is an

integrated theory about the human auditory system rather than a simple heuristic

combination of current signal-processing technologies.

Comment 17See Comment 15.

Another case arises out of short-term memory research. Happily, this one

does not concern limited capacity! When the research technology for short-term

memory studies evolved into a computerized form, it was observed that word

lists presented at objectively regular time intervals (onset to onset times for the

sound envelopes) actually sounded irregular. In order to be perceived as regular

the onset to onset times need to be adjusted so that the “perceptual centers” of the

words occur at equal intervals (Morton, Marcus, & Frankish, 1976). This

science base representation, and algorithms derived from it, can find direct use in

telecommunications technology or speech interfaces where there is a requirement

for the automatic generation of natural sounding number or option sequences.

Comment 18See also Comments 15 and 17.

Of course, both of these examples are admittedly relatively “low level.” For

many higher level aspects of cognition, what is in the science base are

representations of laboratory phenomena of restricted scope and accounts of

them. What would be needed in the science base to provide conditions for

bridging are representations of phenomena much closer to those that occur in the

real world. So, for example, the theoretical representations should be topicalized

on phenomena that really matter in applied contexts (Landauer, 1987). They

should be theoretical representations dealing with extended sequences of

cognitive behavior rather than discrete acts. They should be representations of

information-rich environments rather than information-impoverished ones. They

should relate to circumstances where cognition is not a pattern of short repeating

(experimental) cycles but where any cycles that might exist have meaning in

relation to broader task goals and so on.

Comment 19The behaviours required to undertake and to complete such tasks as desired would need to be included at lower levels of any applied framework.

It is not hard to pursue points about what the science base might incorporate

in a more ideal world. Nevertheless, it does contain a good deal of useful

knowledge (cf. Norman, 1986), and indeed the first life cycle of HCI research

has contributed to it. Many of the major problems with the appropriateness,

scope, integration, and applicability of its content have been identified. Because

major theoretical prestroika will not be achieved overnight, the more productive

questions concern the limitations on the bridging representations of that first

cycle of research and how discovery representations and applications

representations might be more effectively developed in subsequent cycles.

An Analogy with Interface Design Practice

Not surprisingly, those involved in the first life cycle of HCI research relied very

heavily in the formation of their discovery representations on the methodologies

of the parent discipline. Likewise, in bridging from theory to application, those

involved relied heavily on the standard historical products used in the verification

of basic theory, that is, prediction of patterns of time and/or errors.

Comment 20See also Comments 15, 17 and 18.

There are relatively few examples where other attributes of behavior are modeled, such as

choice among action sequences (but see Young & MacLean, 1988). A simple

bridge, predictive of times of errors, provides information about the user of an

interactive system. The user of that information is the designer, or more usually

the design team. Frameworks are generally presented for how that information

might be used to support design choice either directly (e.g., Card et al., 1983) or

through trade-off analyses (e.g., Norman, 1983). However, these forms of

application bridge are underdeveloped to meet the real needs of designers.

Given the general dictum of human factors research, “Know the user”

(Hanson, 1971), it is remarkable how few explicitly empirical studies of design

decision making are reported in the literature. In many respects, it would not be

entirely unfair to argue that bridging representations between theory and design

have remained problematic for the same kinds of reasons that early interactive

interfaces were problematic. Like glass teletypes, basic psychological

technologies were underdeveloped and, like the early design of command

languages, the interfaces (application representations) were heuristically

constructed by applied theorists around what they could provide rather than by

analysis of requirements or extensive study of their target users or the actual

context of design (see also Bannon & BØdker, this volume; Henderson, this

volume).

Equally, in addressing questions associated with the relationship between

theory and design, the analogy can be pursued one stage further by arguing for

the iterative design of more effective bridging structures. Within the first life

cycle of HCI research a goodly number of lessons have been learned that could

be used to advantage in a second life cycle. So, to take a very simple example,

certain forms of modeling assume that users naturally choose the fastest method

for achieving their goal. However there is now some evidence that this is not

always the case (e.g., MacLean, Barnard, & Wilson, 1985). Any role for the

knowledge and theory embodied in the science base must accommodate, and

adapt to, those lessons. For many of the reasons that Carroll and others have

elaborated, simple deductive bridging is problematic. To achieve impact,

behavioral engineering research must itself directly support the design,

development, and invention of artifacts. On any reasonable time scale there is a

need for discovery and application representations that cannot be fully justified

through science-base principles or data. Nonetheless, such a requirement simply

restates the case for some form of cognitive engineering paradigm. It does not in

and of itself undermine the case for the longer-term development of applicable

theory.

Comment 21A cognitive engineering paradigm would not have the same discipline general problem as a cognitive scientific paradigm – the former would be understanding and the latter design. In addition, both would have its own different knowledge in the form of models and methods and practices (the former the diagnosis of design problems of humans interacting with computers and the prescription of their associated design solutions, the latter the explanation and prediction of phenomena, associated with humans interacting with computers.

Just as impact on design has most readily been achieved through the

application of psychological reasoning in the invention and demonstration of

artifacts, so a meaningful impact of theory might best be achieved through the

invention and demonstration of novel forms of applications representations. The

development of representations to bridge from theory to application cannot be

taken in isolation. It needs to be considered in conjunction with the contents of

the science base itself and the appropriateness of the discovery representations

that give rise to them.

Without attempting to be exhaustive, the remainder of this chapter will

exemplify how discovery representations might be modified in the second life

cycle of HCI research; and illustrate how theory might drive, and itself benefit

from, the invention and demonstration of novel forms of applications bridging.

Enhancing Discovery Representations

Although disciplines like psychology have a formidable array of methodological

techniques, those techniques are primarily oriented toward hypothesis testing.

Here, greatest effort is expended in using factorial experimental designs to

confirm or disconfirm a specific theoretical claim. Often wider characteristics of

phenomena are only charted as and when properties become a target of specific

theoretical interest. Early psycholinguistic research did not start off by studying

what might be the most important factors in the process of understanding and

using textual information. It arose out of a concern with transformational

grammars (Chomsky, 1957). In spite of much relevant research in earlier

paradigms (e.g., Bartlett, 1932), psycholinguistics itself only arrived at this

consideration after progressing through the syntax, semantics, and pragmatics of

single-sentence comprehension.

As Landauer (1987) has noted, basic psychology has not been particularly

productive at evolving exploratory research paradigms. One of the major

contributions of the first life cycle of HCI research has undoubtedly been a

greater emphasis on demonstrating how such empirical paradigms can provide

information to support design (again, see Landauer, 1987). Techniques for

analyzing complex tasks, in terms of both action decomposition and knowledge

requirements, have also progressed substantially over the past 20 years (e.g.,

Wilson, Barnard, Green, & MacLean, 1988).

Comment 22Any applied framework must ultimately include levels of description, which capture the behaviours performed in complex tasks and associated with the action decomposition and knowledge requirements, referenced here.

A significant number of these developments are being directly assimilated

into application representations for supporting artifact development. Some can

also be assimilated into the science base, such as Lewis’s (1988) work on

abduction. Here observational evidence in the domain of HCI (Mack et al.,

1983) leads directly to theoretical abstractions concerning the nature of human

reasoning. Similarly, Carroll (1985) has used evidence from observational and

experimental studies in HCI to extend the relevant science base on naming and

reference. However, not a lot has changed concerning the way in which

discovery representations are used for the purposes of assimilating knowledge to

the science base and developing theory.

In their own assessment of progress during the first life cycle of HCI

research, Newell and Card (1985) advocate continued reliance on the hardening

of HCI as a science. This implicitly reinforces classic forms of discovery

representations based upon the tools and techniques of parent disciplines. Heavy

reliance on the time-honored methods of experimental hypothesis testing in

experimental paradigms does not appear to offer a ready solution to the two

problems dealing with theoretical scope and the speed of theoretical advance.

Likewise, given that these parent disciplines are relatively weak on exploratory

paradigms, such an approach does not appear to offer a ready solution to the

other problems of enhancing the science base for appropriate content or for

directing its efforts toward the theoretical capture of effects that really matter in

applied contexts.

The second life cycle of research in HCI might profit substantially by

spawning more effective discovery representations, not only for assimilation to

applications representations for cognitive engineering, but also to support

assimilation of knowledge to the science base and the development of theory.

Two examples will be reviewed here. The first concerns the use of evidence

embodied in HCI scenarios (Young & Barnard, 1987, Young, Barnard, Simon,

& Whittington, 1989). The second concerns the use of protocol techniques to

systematically sample what users know and to establish relationships between

verbalizable knowledge and actual interactive performance.

Test-driving Theories

Young and Barnard (1987) have proposed that more rapid theoretical advance

might be facilitated by “test driving” theories in the context of a systematically

sampled set of behavioral scenarios. The research literature frequently makes

reference to instances of problematic or otherwise interesting user-system

exchanges. Scenario material derived from that literature is selected to represent

some potentially robust phenomenon of the type that might well be pursued in

more extensive experimental research. Individual scenarios should be regarded

as representative of the kinds of things that really matter in applied settings. So

for example, one scenario deals with a phenomenon often associated with

unselected windows. In a multiwindowing environment a persistent error,

frequently committed even by experienced users, is to attempt some action in

inactive window. The action might be an attempt at a menu selection. However,

pointing and clicking over a menu item does not cause the intended result; it

simply leads to the window being activated. Very much like linguistic test

sentences, these behavioral scenarios are essentially idealized descriptions of

such instances of human-computer interactions.

If we are to develop cognitive theories of significant scope they must in

principle be able to cope with a wide range of such scenarios. Accordingly, a

manageable set of scenario material can be generated that taps behaviors that

encompass different facets of cognition. So, a set of scenarios might include

instances dealing with locating information in a directory entry, selecting

alternative methods for achieving a goal, lexical errors in command entry, the

unselected windows phenomenon, and so on (see Young, Barnard, Simon, &

Whittington, 1989). A set of contrasting theoretical approaches can likewise be

selected and the theories and scenarios organized into a matrix. The activity

involves taking each theoretical approach and attempting to formulate an account

of each behavioral scenario. The accuracy of the account is not at stake. Rather,

the purpose of the exercise is to see whether a particular piece of theoretical

apparatus is even capable of giving rise to a plausible account. The scenario

material is effectively being used as a set of sufficiency filters and it is possible to

weed out theories of overly narrow scope. If an approach is capable of

formulating a passable account, interest focuses on the properties of the account

offered. In this way, it is also possible to evaluate and capitalize on the

properties of theoretical apparatus and do provide appropriate sorts of analytic

leverage over the range of scenarios examined.

Comment 23The notion of ‘sufficiency filter’ is an interesting one. However, ultimately it needs to be integrated with other concepts, supporting the notion of validation – conceptualisation; operationalisation; test; and generalisation with respect to understanding or design (or both). See also Comment 15.

Traditionally, theory development places primary emphasis on predictive

accuracy and only secondary emphasis on scope.

Comment 24

Prediction and scope, at the end of the day, cannot be separated. Prediction cannot be tsted in the absence of a stated scope.

This particular form of discovery representation goes some way toward redressing that

balance. It offers the prospect of getting appropriate and relevant theoretical apparatus in

place on a relatively short time cycle. As an exploratory methodology, it at least

addresses some of the more profound difficulties of interrelating theory and

application. The scenario material makes use of known instances of human-computer

interaction. Because these scenarios are by definition instances of

interactions, any theoretical accounts built around them must of necessity be

appropriate to the domain.

Comment 25To be known as appropriate to the domain, the latter needs to be explicitly included in the theory.

Because scenarios are intended to capture significant

aspects of user behavior, such as persistent errors, they are oriented toward what

matters in the applied context.

Comment 26What matters in an applied context is, more generally, how well a task is performed. That may, or may not, be reflected by errors, persistent or not.

As a quick and dirty methodology, it can make

effective use of the accumulated knowledge acquired in the first life cycle of HCI

research, while avoiding some of the worst “tar pits” (Norman, 1983) of

traditional experimental methods.

Comment 27‘Quick and dirty methodology’ and ‘tar pit’ avoidance need to be integrated with notions of validation, such as – conceptualisation; operationalisation; test; and generalisation. See also Comments 15 and 23.

As a form of discovery bridge between application and theory, the real world

is represented, for some purpose, not by a local observation or example, but by a

sampled set of material. If the purpose is to develop a form of cognitive

architecture , then it may be most productive to select a set of scenarios that

encompass different components of the cognitive system (perception, memory,

decision making, control of action). Once an applications representation has

been formed, its properties might be further explored and tested by analyzing

scenario material sampled over a range of different tasks, or applications

domains (see Young & Barnard, 1987). At the point where an applications

representation is developed, the support it offers may also be explored by

systematically sampling a range of design scenarios and examining what

information can be offered concerning alternative interface options (AMODEUS,

1989). By contrast with more usual discovery representations, the scenario

methodology is not primarily directed at classic forms of hypothesis testing and

validation. Rather, its purpose is to support the generation of more readily

applicable theoretical ideas.

Comment 28Barnard’s point is well taken here. However, the ‘more applicable theoretical ideas have still to be validated with respect to design. See also Comments 15, 17 and 27.

Verbal Protocols and Performance

One of the most productive exploratory methodologies utilized in HCI research

has involved monitoring user action while collecting concurrent verbal protocols

to help understand what is actually going on. Taken together these have often

given rise to the best kinds of problem-defining evidence, including the kind of

scenario material already outlined. Many of the problems with this form of

evidence are well known. Concurrent verbalization may distort performance and

significant changes in performance may not necessarily be accompanied by

changes in articulatable knowledge. Because it is labor intensive, the

observations are often confined to a very small number of subjects and tasks. In

consequence, the representatives of isolated observations is hard to assess.

Furthermore, getting real scientific value from protocol analysis is crucially

dependent on the insights and craft skill of the researcher concerned (Barnard,

Wilson, & MacLean, 1986; Ericsson & Simon, 1980).

Techniques of verbal protocol analysis can nevertheless be modified and

utilized as a part of a more elaborate discovery representation to explore and

establish systematic relationships between articulatable knowledge and

performance. The basic assumption underlying much theory is that a

characterization of the ideal knowledge a user should possess to successfully

perform a task can be used to derive predictions about performance. However,

protocol studies clearly suggest that users really get into difficulty when they

have erroneous or otherwise nonideal knowledge. In terms of the precise

relationships they have with performance, ideal and nonideal knowledge are

seldom considered together.

In an early attempt to establish systematic and potentially generalizable

relationships between the contents of verbal protocols and interactive

performance, Barnard et al., (1986) employed a sample of picture probes to elicit

users’ knowledge of tasks, states, and procedures for a particular office product

at two stages of learning. The protocols were codified, quantified, and

compared. In the verbal protocols, the number of true claims about the system

increased with system experience, but surprisingly, the number of false claims

remained stable. Individual users who articulated a lot of correct claims

generally performed well, but the amount of inaccurate knowledge did not appear

related to their overall level of performance. There was, however, some

indication that the amount of inaccurate knowledge expressed in the protocols

was related to the frequency of errors made in particular system contexts.

A subsequent study (Barnard, Ellis, & MacLean, 1989) used a variant of the

technique to examine knowledge of two different interfaces to the same

application functionality. High levels of inaccurate knowledge expressed in the

protocols were directly associated with the dialogue components on which

problematic performance was observed. As with the earlier study, the amount of

accurate knowledge expressed in any given verbal protocol was associated with

good performance, whereas the amount of inaccurate knowledge expressed bore

little relationship to an individual’s overall level of performance. Both studies

reinforced the speculation that is is specific interface characteristics that give rise

to the development of inaccurate or incomplete knowledge from which false

inferences and poor performance may follow.

Just as the systematic sampling and use of behavioral scenarios may facilitate

the development of theories of broader scope, so discovery representations

designed to systematically sample the actual knowledge possessed by users

should facilitate the incorporation into the science base of behavioral regularities

and theoretical claims that are more likely to reflect the actual basis of user

performance rather than a simple idealization of it.

Enhancing Application Representations

The application representations of the first life cycle of HCI research relied very

much on the standard theoretical products of their parent disciplines.

Grammatical techniques originating in linguistics were utilized to characterize the

complexity of interactive dialogues; artificial intelligence (A1)-oriented models

were used to represent and simulate the knowledge requirements of learning;

and, of course, derivatives of human information-processing models were used

to calculate how long it would take users to do things. Although these

approaches all relied upon some form of task analysis, their apparatus was

directed toward some specific function. They were all of limited scope and made

numerous trade-offs between what was modeled and the form of prediction made

(Simon, 1988).

Some of the models were primarily directed at capturing knowledge

requirements for dialogues for the purposes of representing complexity, such as

BNF grammars (Reisner, 1982) and Task Action Grammars (Payne & Green,

1986). Others focused on interrelationships between task specifications and

knowledge requirements, such as GOMS analyses and cognitive-complexity

theory (Card et al. 1983; Kieras & Polson, 1985). Yet other apparatus, such as

the model human information processor and the keystroke level model of Card et al.

(1983) were primarily aimed at time prediction for the execution of error-free

routine cognitive skill. Most of these modeling efforts idealized either the

knowledge that users needed to possess or their actual behavior. Few models

incorporated apparatus for integrating over the requirements of knowledge

acquisition or use and human information-processing constraints (e.g., see

Barnard, 1987). As application representations, the models of the first life cycle

had little to say about errors or the actual dynamics of user-system interaction as

influenced by task constraints and information or knowledge about the domain of

application itself.

Two modeling approaches will be used to illustrate how applications

representations might usefully be enhanced. They are programmable user

models (Young, Green, & Simon, 1989) and modeling based on Interacting

Cognitive Subsystems (Barnard, 1985). Although these approaches have

different origins, both share a number of characteristics. They are both aimed at

modeling more qualitative aspects of cognition in user-system interaction; both

are aimed at understanding how task, knowledge, and processing constraint

intersect to determine performance; both are aimed at exploring novel means of

incorporating explicit theoretical claims into application representations; and both

require the implementation of interactive systems for supporting decision making

in a design context. Although they do so in different ways, both approaches

attempt to preserve a coherent role for explicit cognitive theory. Cognitive theory

is embodied, not in the artifacts that emerge from the development process, but

in demonstrator artifacts that might emerge from the development process, but in

demonstrator artifacts that might support design. This is almost directly

analogous to achieving an impact in the marketplace through the application of

psychological reasoning in the invention of artifacts. Except in this case, the

target user populations for the envisaged artifacts are those involved in the design

and development of products.

Programmable User Models (PUMs)

The core ideas underlying the notion of a programmable user model have their

origins in the concepts and techniques of AI. Within AI, cognitive architectures

are essentially sets of constraints on the representation and processing of

knowledge. In order to achieve a working simulation, knowledge appropriate to

the domain and task must be represented within those constraints. In the normal

simulation methodology, the complete system is provided with some data and,

depending on its adequacy, it behaves with more or less humanlike properties.

Using a simulation methodology to provide the designer with an artificial

user would be one conceivable tactic. Extending the forms of prediction offered

by such simulations (cf. cognitive complexity theory; Polson, 1987) to

encompass qualitative aspects of cognition is more problematic. Simply

simulating behavior is of relatively little value. Given the requirements of

knowledge-based programming, it could, in many circumstances, be much more

straightforward to provide a proper sample of real users. There needs to be

some mechanism whereby the properties of the simulation provide information

of value in design. Programmable user models provide a novel perspective on

this latter problem. The idea is that the designer is provided with two things, an

“empty” cognitive architecture and an instruction language for providing with all

the knowledge it needs to carry out some task. By programming it, the designer

has to get the architecture to perform that task under conditions that match those

of the interactive system design (i.e., a device model). So, for example, given a

particular dialog design, the designer might have to program the architecture to

select an object displayed in a particular way on a VDU and drag it across that

display to a target position.

The key, of course, is that the constraints that make up the architecture being

programmed are humanlike. Thus, if the designer finds it hard to get the

architecture to perform the task, then the implication is that a human user would

also find the task hard to accomplish. To concretize this, the designer may find

that the easiest form of knowledge-based program tends to select and drag the

wrong object under particular conditions. Furthermore, it takes a lot of thought

and effort to figure out how to get round this problem within the specific

architectural constraints of the model. Now suppose the designer were to adjust

the envisaged user-system dialog in the device model and then found that

reprogramming the architecture to carry out the same task under these new

conditions was straightforward and the problem of selecting the wrong object no

longer arose. Young and his colleagues would then argue that this constitutes

direct evidence that the second version of the dialog design tried by the designer

is likely to prove more usable than the first.

The actual project to realize a working PUM remains at an early stage of

development. The cognitive architecture being used is SOAR (Laird, Newell, &

Rosenbloom, 1987). There are many detailed issues to be addressed concerning

the design of an appropriate instruction language. Likewise, real issues are

raised about how a model that has its roots in architectures for problem solving

(Newell & Simon, 1972) deals with the more peripheral aspects of human

information processing, such as sensation, perception, and motor control.

Nevertheless as an architecture, it has scope in the sense that a broad range of

tasks and applications can be modeled within it. Indeed, part of the motivation

of SOAR is to provide a unified general theory of cognition (Newell, 1989).

In spite of its immaturity, additional properties of the PUM concept as an

application bridging structure are relatively clear (see Young et al., 1989). First,

programmable user models embody explicit cognitive theory in the form of the

to-be-programmed architecture. Second, there is an interesting allocation of

function between the model and the designer. Although the modeling process

requires extensive operationalization of knowledge in symbolic form, the PUM

provides only the constraints and the instruction language, whereas the designer

provides the knowledge of the application and its associated tasks. Third,

knowledge in the science base is transmitted implicitly into the design domain via

an inherently exploratory activity. Designers are not told about the underlying

cognitive science; they are supposed to discover it. By doing what they know

how to do well – that is, programming – the relevant aspects of cognitive

constraints and their interactions with the application should emerge directly in

the design context.

Fourth, programmable user models support a form of qualitative predictive

evaluation that can be carried out relatively early in the design cycle. What that

evaluation provides is not a classic predictive product of laboratory theory, rather

it should be an understanding of why it is better to have the artifact constructed

one way rather than another. Finally, although the technique capitalizes on the

designer’s programming skills, it clearly requires a high degree of commitment

and expense. The instruction language has to be learned and doing the

programming would require the development team to devote considerable

resources to this form of predictive evaluation.

Approximate Models of Cognitive Activity

Interacting Cognitive Subsystems (Barnard, 1985) also specifies a form of

cognitive architecture. Rather than being an AI constraint-based architecture,

ICS has its roots in classic human information-processing theory. It specifies

the processing and memory resources underlying cognition, the organization of

these resources, and principles governing their operation. Structurally, the

complete human information-processing system is viewed as a distributed

architecture with functionally distinct subsystems each specializing in, and

supporting, different types of sensory, representational, and effector processing

activity. Unlike many earlier generations of human information-processing

models, there are no general purpose resources such as a central executive or

limited capacity working memory. Rather the model attempts to define and

characterize processes in terms of the mental representations they take as input

and the representations they output. By focusing on the mappings between

different mental representations, this model seeks to integrate a characterization

of knowledge-based processing activity with classic structural constraints on the

flow of information within the wider cognitive system.

A graphic representation of this architecture is shown in the right-hand panel

of Figure 7.2, which instantiates Figure 7.1 for the use of the ICS framework in

an HCI context. The architecture itself is part of the science base. Its initial

development was supported by using empirical evidence from laboratory studies

of short-term memory phenomena (Barnard, 1985). However, by concentrating

on the different types of mental representation and process that transform them,

rather than task and paradigm specific concepts, the model can be applied across

a broad range of settings (e.g., see Barnard & Teasdale, 1991). Furthermore,

for the purposes of constructing a representation to bridge between theory and

application it is possible to develop explicit, yet approximate, characterizations of

cognitive activity.

In broad terms, the way in which the overall architecture will behave is

dependent upon four classes of factor. First, for any given task it will depend on

the precise configuration of cognitive activity. Different subsets of processes

and memory records will be required by different tasks. Second, behavior will

be constrained by the specific procedural knowledge embodied in each mental

process that actually transforms one type of mental representation to another.

Third, behavior will be constrained by the form, content, and accessibility of any

memory records that are need in that phase of activity. Fourth, it will depend on

the overall way in which the complete configuration is coordinated and

controlled.

Because the resources are relatively well defined and constrained in terms of

their attributes and properties, interdependencies between them can be motivated

on the basis of known patterns of experimental evidence and rendered explicit.

So, for example, a complexity attribute of the coordination and control of

cognitive activity can be directly related to the number of incompletely

proceduralized processes within a specified configuration. Likewise, a strategic

attribute of the coordination and control of cognitive activity may be dependent

upon the overall amount of order uncertainty associated with the mental

representation of a task stored in a memory record. For present purposes the

precise details of these interdependencies do not matter, nor does the particularly

opaque terminology shown in the rightmost panel of Figure 7.2 (for more

details, see Barnard, 1987). The important point is that theoretical claims can be

specified within this framework at a high level of abstraction and that these

abstractions belong in the science base.

Although these theoretical abstractions could easily have come from classic

studies of human memory and performance, there were in fact motivated by

experimental studies of command naming in text editing (Grudin & Barnard,

1984) and performance on an electronic mailing task (Barnard, MacLean, &

Hammond, 1984). The full theoretical analyses are described in Barnard (1987)

and extended in Barnard, Grudin, and MacLean (1989). In both cases the tasks

were interactive, involved extended sequences of cognitive behavior, involved

information-rich environments, and the repeating patterns of data collection were

meaningful in relation to broader task goals not atypical of interactive tasks in the

real world. In relation to the arguments presented earlier in this chapter, the

information being assimilated to the science base should be more appropriate and

relevant to HCI than that derived from more abstract laboratory paradigms. It

will nonetheless be subject to interpretive restrictions inherent in the particular

form of discovery representation utilized in the design of these particular

experiments.

Armed with such theoretical abstractions, and accepting their potential

limitations, it is possible to generate a theoretically motivated bridge to

application. The idea is to build approximate models that describe the nature of

cognitive activity underlying the performance of complex tasks. The process is

actually carried out by an expert system that embodies the theoretical knowledge

required to build such models. The system “knows” what kinds of

configurations are associated with particular phases of cognitive activity; it

“knows” something about the conditions under which knowledge becomes

proceduralized, and the properties of memory records that might support recall

and inference in complex task environments. It also “knows” something about

the theoretical interdependencies between these factors in determining the overall

patterning, complexity, and qualities of the coordination and dynamic control of

cognitive activity. Abstract descriptions of cognitive activity are constructed in

terms of a four-component model specifying attributes of configurations,

procedural knowledge, record contents, and dynamic control. Finally, in order

to produce an output, the system “knows” something about the relationships

between these abstract models of cognitive activity and the attributes of user

behaviour.

Figure 7.2. The applied science paradigm instantiated for the use of interacting cognitive subsystems as a theoretical basis for the development of expert system design aid.

Obviously, no single model of this type can capture everything that goes on

in a complex task sequence. Nor can a single model capture different stages of

user development or other individual differences within the user population. It is

therefore necessary to build a set of interrelated models representing different

phases of cognitive activity, different levels and forms of user expertise, and so

The basic modeling unit uses the four-component description to characterize

cognitive activity for a particular phase, such as establishing a goal, determining

the action sequence, and executing it. Each of these models approximates over

the very short-term dynamics of cognition. Transitions between phases

approximate over the short-term dynamics of tasks, whereas transitions between

levels of expertise approximate over different stages of learning. In Figure 7.2,

the envisaged application representation thus consists of a family of interrelated

models depicted graphically as a stack of cards.

Like the concept of programmable user models, the concept of approximate

descriptive modeling is in the course of development. A running demonstrator

system exists that effectively replicates the reasoning underlying the explanation

of a limited range of empirical phenomena in HCI research (see Barnard,

Wilson, & MacLean, 1987, 1988). What actually happens is that the expert

system elicits, in a context-sensitive manner, descriptions of the envisaged

interface, its users, and the tasks that interface is intended to support. It then

effectively “reasons about” cognitive activity, its properties, and attributes in that

applications setting for one or more phases of activity and one or more stages of

learning. Once the models have stabilized, it then outputs a characterization of

the probable properties of user behavior. In order to achieve this, the expert

system has to have three classes of rules: those that map from descriptions of

tasks, users, and systems to entities and properties in the model representation;

rules that operate on those properties; and rules that map from the model

representation to characterizations of behavior. Even in its somewhat primitive

current state, the demonstrator system has interesting generalizing properties.

For example, theoretical principles derived from research on rather antiquated

command languages support limited generalization to direct manipulation and

iconic interfaces.

As an applications representation, the expert system concept is very different

from programmable user models. Like PUMs, the actual tool embodies explicit

theory drawn from the science base. Likewise, the underlying architectural

concept enables a relatively broad range of issues to be addressed. Unlike

PUMs, it more directly addresses a fuller range of resources across perceptual,

cognitive, and effector concerns. It also applies a different trade-off in when and

by whom the modeling knowledge is specified. At the point of creation, the

expert system must contain a complete set of rules for mapping between the

world and the model. In this respect, the means of accomplishing and

expressing the characterizations of cognition and behavior must be fully and

comprehensively encoded. This does not mean that the expert system must

necessarily “know” each and every detail. Rather, within some defined scope,

the complete chain of assumptions from artifact to theory and from theory to

behavior must be made explicit at an appropriate level of approximation.

Comment 29This cycle is the basis and justification for the inclusion of Barnard’s paper as an applied framework.

Equally, the input and output rules must obviously be grounded in the language

of interface description and user-system interaction. Although some of the

assumptions may be heuristic, and many of them may need crafting, both

theoretical and craft components are there. The how-to-do-it modeling

knowledge is laid out for inspection.

Comment 30See Comments 19 and 22, concerning the framework requirements for the low levels of the description of humans interacting with computers involved in their design.

However, at the point of use, the expert system requires considerably less

precision than PUMs in the specification and operationalization of the knowledge

required to use the application being considered. The expert system can build a

family of models very quickly and without its user necessarily acquiring any

great level of expertise in the underlying cognitive theory. In this way, it is

possible for that user to explore models for alternative system designs over the

course of something like one afternoon. Because the system is modular, and the

models are specified in abstract terms, it is possible in principle to tailor the

systems input and output rules without modifying the core theoretical reasoning.

The development of the tool could then respond to requirements that might

emerge from empirical studies of the real needs of design teams or of particular

application domains.

In a more fully developed form, it might be possible to address the issue of

which type of tool might prove more effective in what types of applications

context. However, strictly speaking, they are not direct competitors, they are

alternative types of application representation that make different forms of tradeoff

about the characteristics of the complete chain of bridging from theory to

application. By contrast with the kinds of theory-based techniques relied on in

the first life cycle of HCI research, both PUMs and the expert-system concept

represent more elaborate bridging structures. Although underdeveloped, both

approaches are intended ultimately to deliver richer and more integrated

information about properties of human cognition into the design environment in

forms in which it can be digested and used. Both PUMs and the expert system

represent ways in which theoretical support might be usefully embodied in future

generations of tools for supporting design. In both cases the aim is to deliver

within the lifetime of the next cycle of research a qualitative understanding of

what might be going on in a user’s head rather than a purely quantitative estimate

of how long the average head is going to be busy (see also Lewis, this volume).

Summary

The general theme that has been pursued in this chapter is that the relationship

between the real world and theoretical representations of it is always mediated by

bridging representations that subserve specific purposes. In the first life cycle of

research on HCI, the bridging representations were not only simple, they were

only a single step away from those used in the parent disciplines for the

development of basic theory and its validation. If cognitive theory is to find any

kind of coherent and effective role in forthcoming life cycles of HCI research, it

must seriously reexamine the nature and function of these bridging

representations as well as the content of the science base itself.

This chapter has considered bridging between specifically cognitive theory

and behavior in human-computer interaction. This form of bridging is but one

among many that need to be pursued. For example, there is a need to develop

bridging representations that will enable us to interrelate models of user cognition

with the formed models being developed to support design by software

engineers (e.g., Dix, Harrison, Runciman, & Thimbleby, 1987; Harrison,

Roast, & Wright, 1989; Thimbleby, 1985). Similarly there is a need to bridge

between cognitive models and aspects of the application and the situation of use

(e.g., Suchman, 1987). Truly interdisciplinary research formed a large part of

the promise, but little of the reality of early HCI research. Like the issue of

tackling nonideal user behavior, interdisciplinary bridging is now very much on

the agenda for the next phase of research (e.g., see Barnard & Harrison, 1989).

The ultimate impact of basic theory on design can only be indirect – through

an explicit application representation. Alternative forms of such representation

that go well beyond what has been achieved to date have to be invented,

developed, and evaluated. The views of Carroll and his colleagues form one

concrete proposal for enhancing our application representations. The design

rationale concept being developed by MacLean, Young, and Moran (1989)

constitutes another potential vehicle for expressing application representations.

Yet other proposals seek to capture qualitative aspects of human cognition while

retaining a strong theoretical character (Barnard et al., 1987; 1988; Young,

Green, & Simon, 1989).

On the view advocated here, the direct theory-based product of an applied

science paradigm operating in HCI is not an interface design. It is an application

representation capable of providing principled support for reasoning about

designs. There may indeed be very few examples of theoretically inspired

software products in the current commercial marketplace. However, the first life

cycle of HCI research has produced a far more mature view of what is entailed in

the development of bridging representations that might effectively support design

reasoning. In subsequent cycles, we may well be able to look forward to a

significant shift in the balance of added value within the interaction between

applied science and design. Although future progress will in all probability

remain less than rapid, theoretically grounded concepts may yet deliver rather

more in the way of principled support for design than has been achieved to date.

Acknowledgments

The participants at the Kittle Inn workshop contributed greatly to my

understanding of the issues raised here. I am particularly indebted to Jack

Carroll, Wendy Kellogg, and John Long, who commented extensively on an

earlier draft. Much of the thinking also benefited substantially from my

involvement with the multidisciplinary AMODEUS project, ESPRIT Basic

Research Action 3066.

References

ACTS (1989). Connectionist Techniques for Speech (Esprit Basic Research

ACtion 3207), Technical Annex. Brussels: CEC.

Basic Theories and the Artifacts of HCI 125

AMODEUS (1989). Assimilating models of designers uses and systems (ESprit

Basic Research Action 3066), Technical Aneex. Brussels; CEC.

Anderson, J. R., & Skwarecki, E. 1986. The automated tutoring of

introductory computer programming. Communications of the ACM, 29,

842-849.

Barnard, P. J. (1985). Interacting cognitive subsystems: A psycholinguistic

approach to short term memory. In A. Ellis, (Ed.), Progress in the

psychology of language (Vol. 2, chapter 6, pp. 197-258. London:

Lawrenece Erlbaum Associates.

Barnard, P. J. (1987). Cognitive resources and the learning of human-computer

dialogs. In J.M. Carroll (Ed.), Interfacing thought: Cognitive aspects of

human-computer interaction (pp. 112-158). Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Barnard, P. J., & Harrison, M. D. (1989). Integrating cognitive and system

models in human-computer interaction. In A. Sutcliffe & L. Macaulay,

(Ed.), People and computers V (pp. 87-103). Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Barnard, P. J., Ellis, J., & MacLean, A. (1989). Relating ideal and non-ideal

verbalised knowledge to performance. In A. Sutcliffe & L. Macaulay

(Eds.), People and computers V (pp. 461-473). Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Barnard, P. J., Grudin, J., & MacLean, A. (1989). Developing a science base

for the naming of computer commands. In J. B. Long & A. Whitefield

(Eds.), Cognitive ergonomics and human-computer interaction (pp. 95-

133). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barnard, P. J., Hammond, N., MacLean, A., & Morton, J. (1982). Learning

and remembering interactive commands in a text-editing task. Behaviour

and Information Technology, 1, 347-358.

Barnard, P. J., MacLean, A., & Hammond, N. V. (1984). User representations

of ordered sequences of command operations. In B. Shackel (Ed.),

Proceedings of Interact ’84: First IFIP Conference on Human-Computer

Interaction, (Vol. 1, pp. 434-438). London: IEE.

Barnard, P. J., & Teasdale, J. (1991). Interacting cognitive subsystems: A

systematic approach to cognitive-affective interaction and change.

Cognition and Emotion, 5, 1-39.

Barnard, P. J., Wilson, M., & MacLean, A. (1986). The elicitation of system

knowledge by picture probles. In M. Mantei & P. Orbeton (Eds.),