MUSE(SE)

MUSE for Software Engineers

Introduction to the Paper

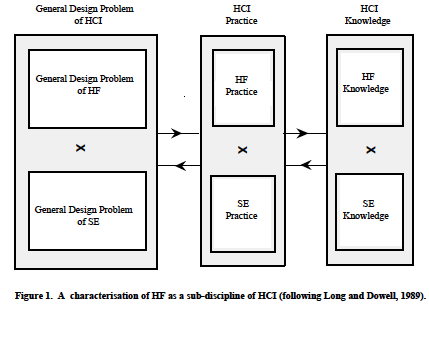

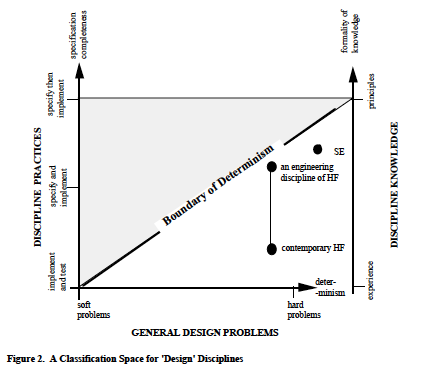

MUSE is a Method for USability Engineering. It seeks to integrate usability into the development of interactive systems. It provides an environment in which human factors contributions can realise their full potential. (Lim and Long, 1994 – Cambridge University Press: Cambridge). MUSE comprises three phases: 1. Elicitation and Analysis; 2. Synthesis; and 3. Design Specification. MUSE is intended for application by human factors engineers. MUSE (SE), the version presented here, is intended for application by software engineers. It contains guidance, for example, concerning why and how to perform task analysis, as well as how to apply heuristics, with both of which human factors engineers would be assumed already familiar. The version of MUSE(SE) presented here was used to evaluate the method against target users. Hence, the specific, testing format.

James Middlemass and John Long, Ergonomics and HCI Unit, University College London

Introduction to James Middlemass

James Middlemass was an MSc student at UCL in the class of 1992/3 and a Research Fellow on European Systems and Software Initiative project 10290, ‘Benefits of Integrating Usability and Software Engineering Methods’. His subsequent work on integrating design knowledge into the MUSE (SE) method led to the version presented here.

Thank you for taking part in the trial application of MUSE(SE).

As the trial is part of a research project, it is important that you follow the procedures as closely as possible.

Please feel free to write on the procedures. Write a note next to any procedures that you find problematic; any comments you want to make whilst following the method, whether positive or negative, will be particularly valuable.

When the application is complete, your comments will be a valuable aspect of the evaluation, and will be used as an input towards future improvements to the method.

If you require help or advice on the method at any point during the test application, please feel free to contact me:

Phone: 0171 504 5316

Fax: 0171 580 1100

Email: j.middlemass@ucl.ac.uk

Contents

Introduction to MUSE(SE) 6

Notations used in MUSE(SE) 9

MUSE(SE) Procedures 12

Introduction 12

Phase 1 14

Extant Systems Analysis Stage 15

Examine Documents 16

Examine systems 17

Familiarise investigator with the system 18

Interview user representatives 20

Record findings 22

Construct ‘typical’ tasks 23

Study the systems 24

Decompose tasks 26

Identify usability requirements 26

OMT Cross-Checking Point 26

GTM stage 28

Generifying tasks 28

GTM Heuristics 30

Generification 32

Preparing GTM(y) 32

Preparing GTM(x) 33

Verify models 33

Phase 2 35

SUN stage 36

Document user problems 36

OMT Cross-Checking Point 39

DoDD(y) stage 41

Production of the DoDD(y) 42

Production of the user object model 43

OMT Cross-Checking Point 47

CTM(y) stage 49

Decompose task 49

Task Synthesis 50

CTM(y) supporting table 50

Allocation of function 51

Verify model 51

CTM Heuristics 52

OMT Cross-Checking Point 53

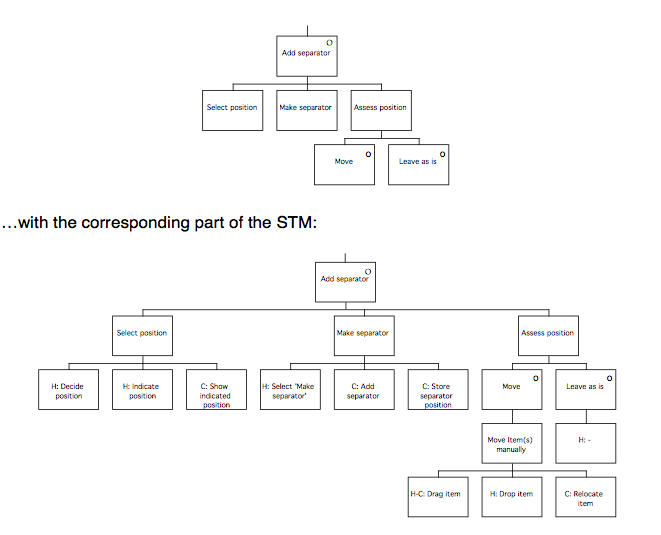

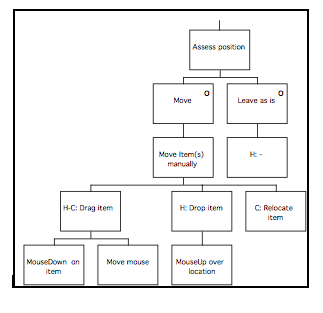

System and User Task Model 55

Decomposition of the CTM(y) 55

Assessing the design 56

Refering back to SUN and DoDD(y) 57

Completing the STM table 57

Document functionality 58

Handshake with SE 58

Phase 3 60

ITM(y) stage 61

Reviewing the STM(y) 61

H-C leaves 61

Referring to the DoDD(y) 62

H leaves 62

ITM diagram and table 63

Iterating the design 63

Locating screen boundaries 64

OMT Cross-Checking Point 66

ITM heuristics 67

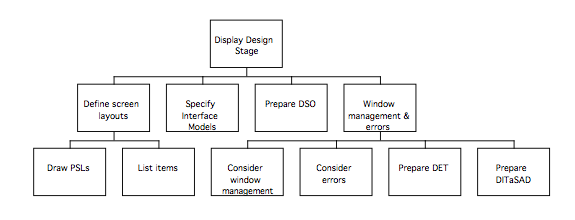

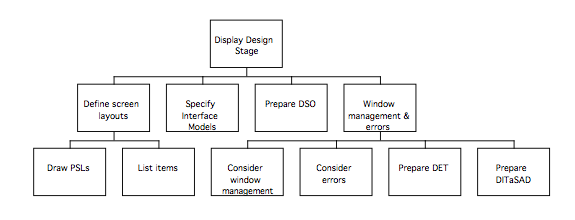

Display Design stage 70

Defining screen layouts 71

Specifying IM(y)s 72

Dictionary of Screen Objects 72

Window management and errors 73

The DITaSAD 74

Display Design Stage Heuristics 75

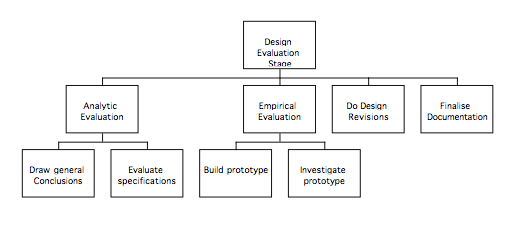

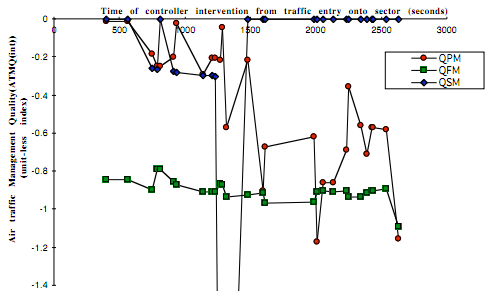

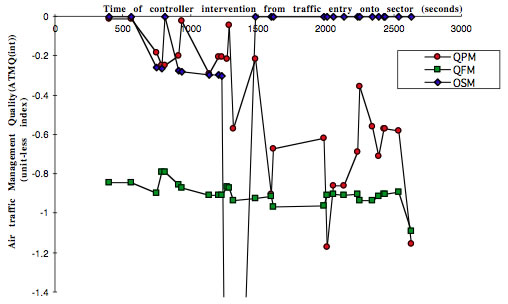

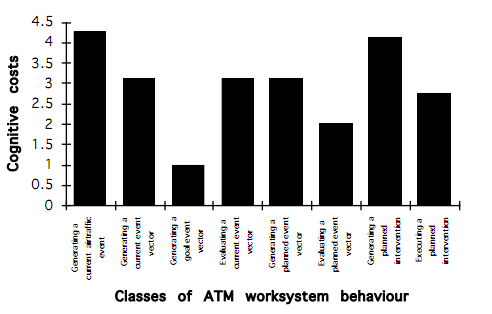

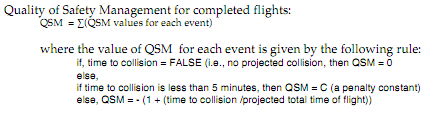

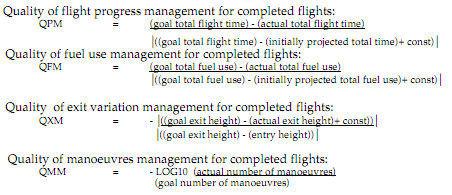

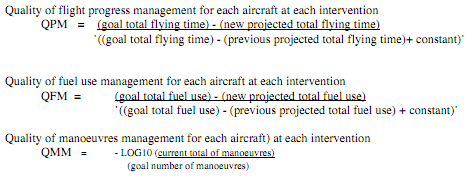

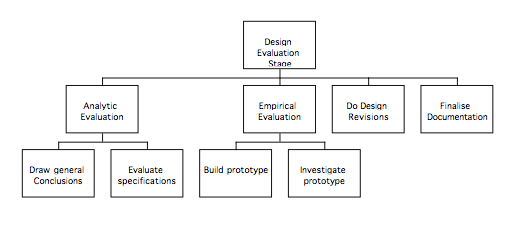

Design Evaluation stage 79

Analytic evaluation 79

Empirical evaluation 80

Deciding where to redesign 84

Finalise documentation 84

Iteration Heuristics 86

Example 89

Extant Systems Analysis Stage 90

Statement of requirements 90

Examining the systems 91

Observational studies 92

Interviewing user representatives 96

‘Mind maps’ from interviews 97

TD(ext) products 98

TD supporting table 100

Tasks for test subjects 101

Usability Testing 102

Extract from the Ravden and Johnson Checklist 103

Choosing related systems 104

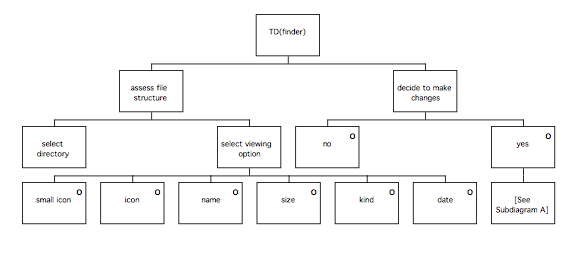

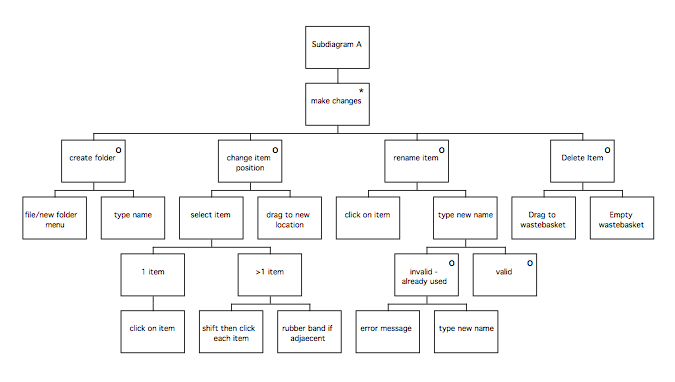

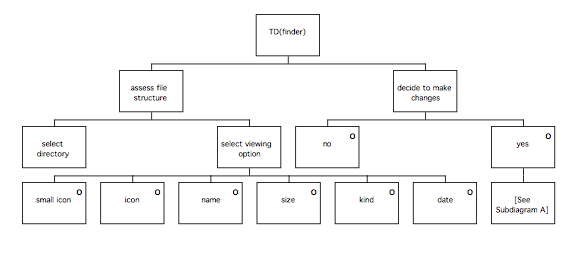

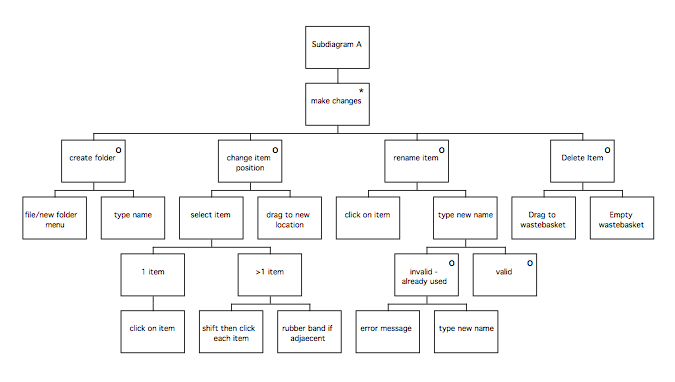

TD(ext) example: Finder 105

Identifying usability requirements 106

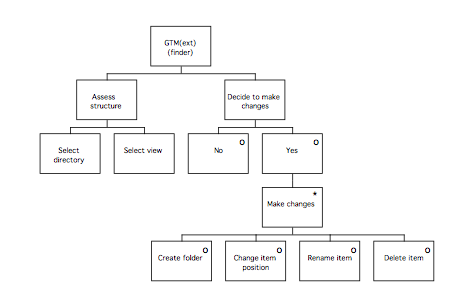

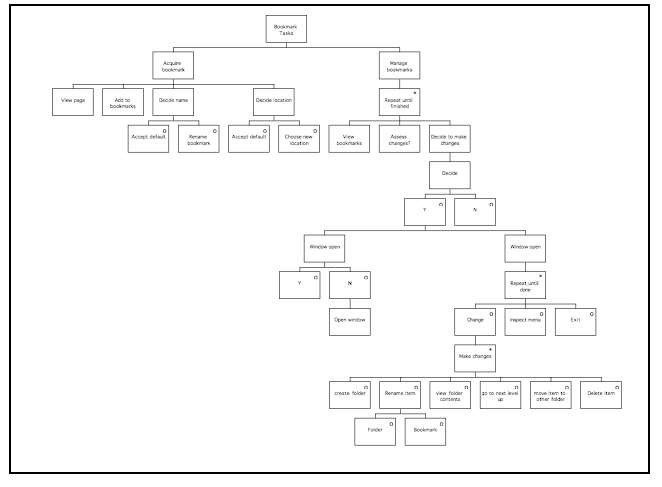

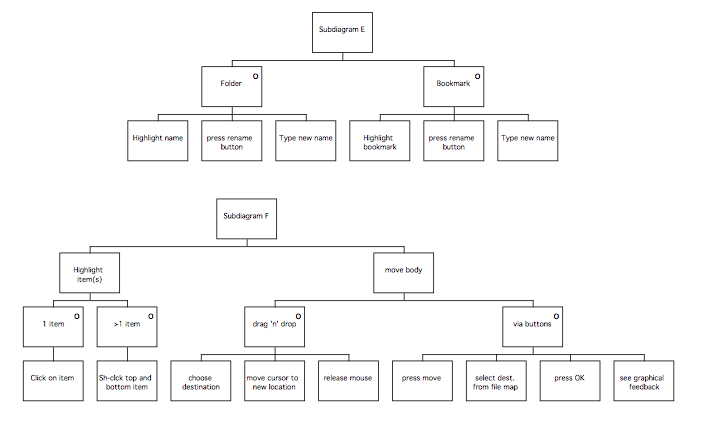

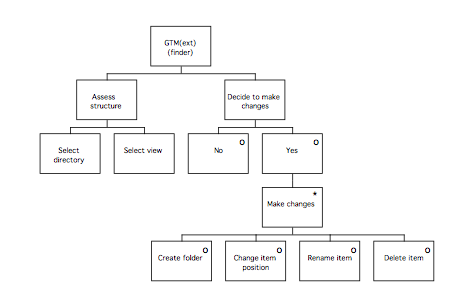

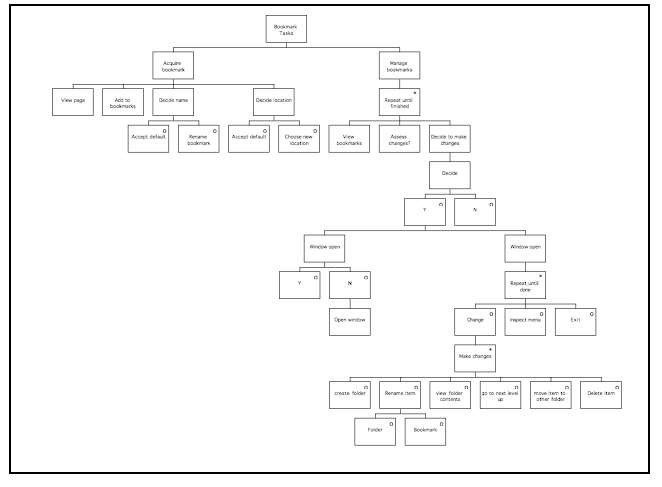

GTM stage 106

GTM(ext) for Finder 106

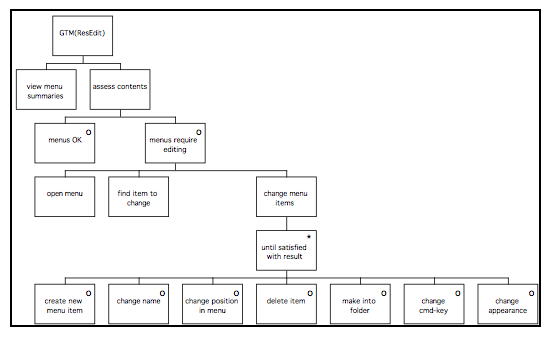

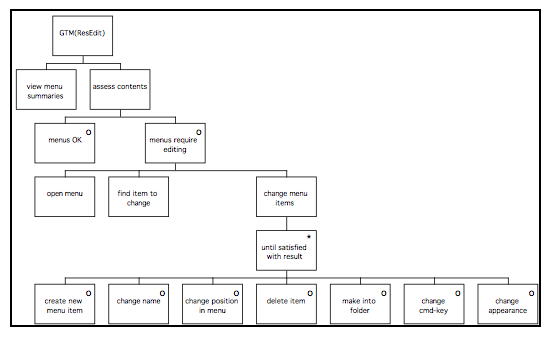

GTM(ext) for ResEdit 106

GTM(ext) for Microsoft Internet Explorer 107

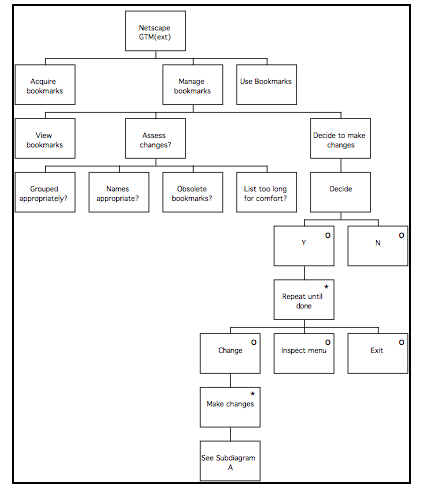

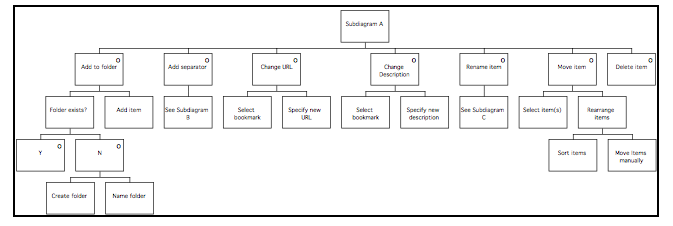

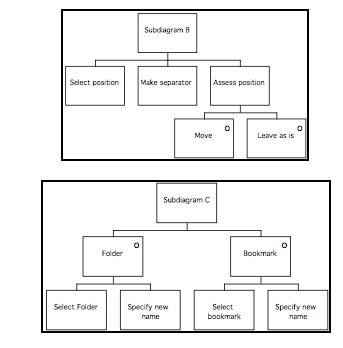

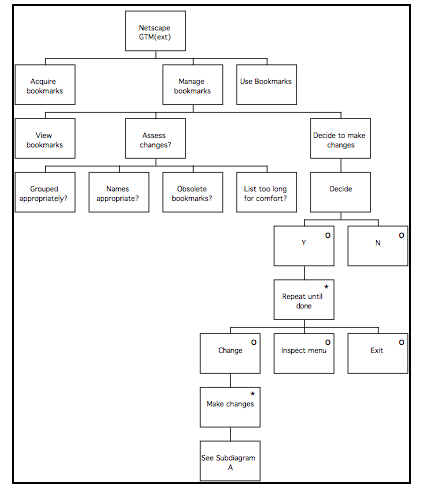

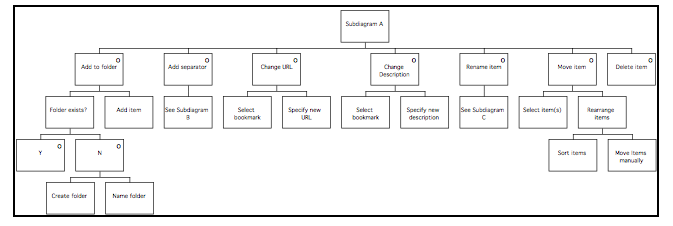

GTM(ext) for NetScape Navigator 107

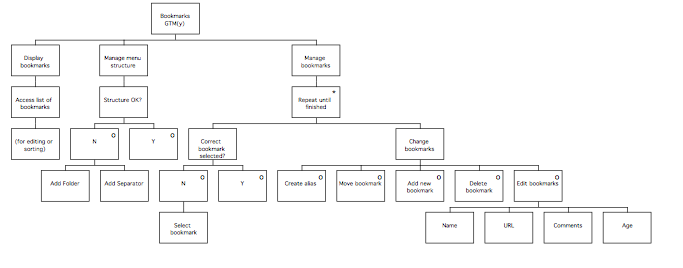

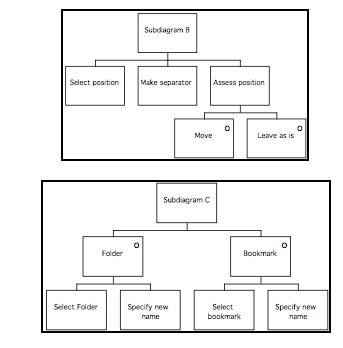

GTM(y) 108

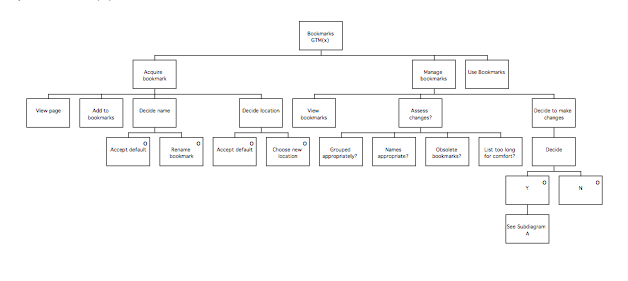

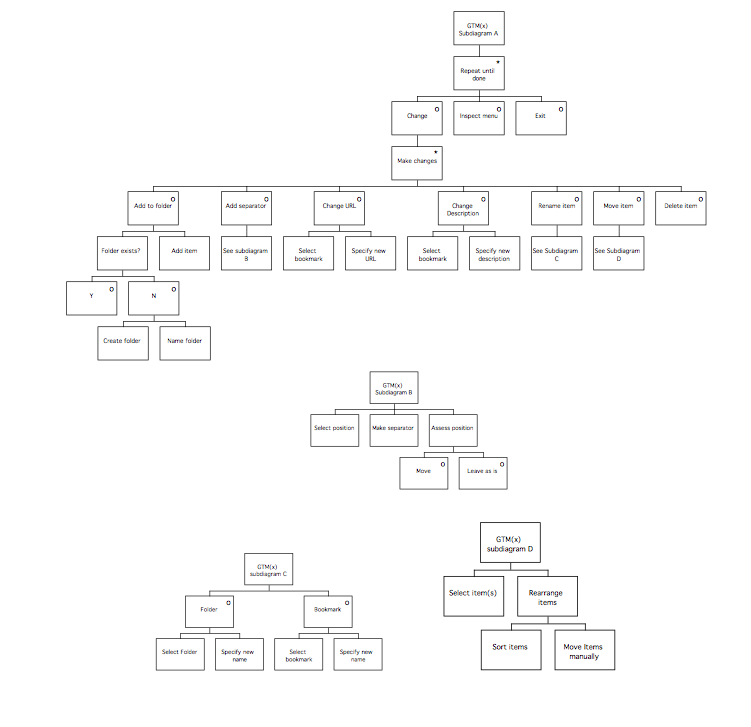

GTM(x) 109

SUN stage 110

Statement of User Needs 110

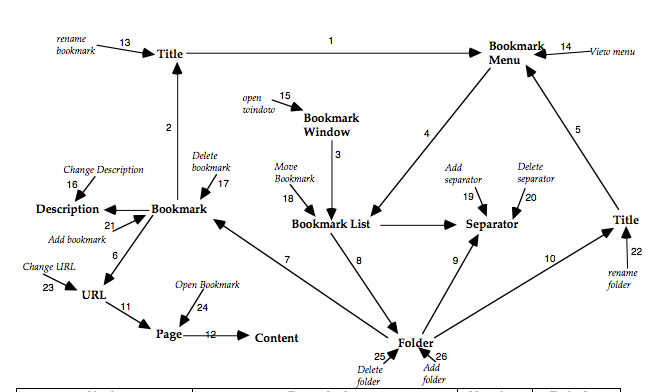

DoDD(y) stage 113

DoDD(y) 113

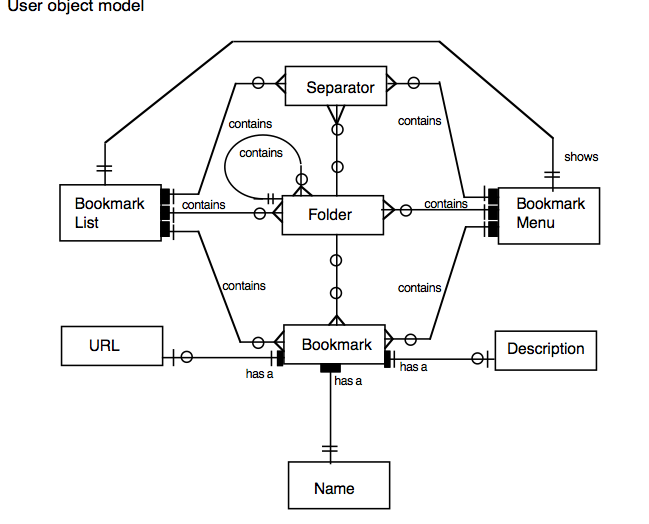

User object model 114

Action – Object Matrix 114

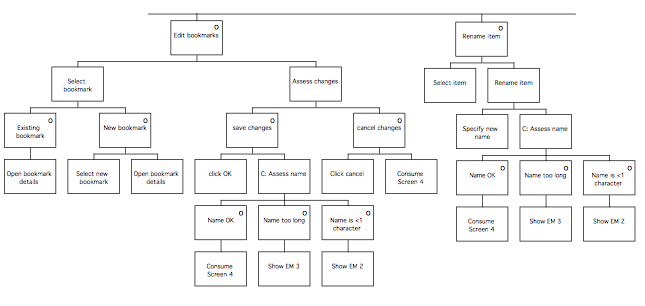

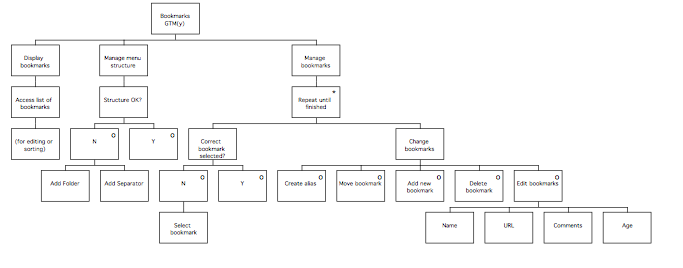

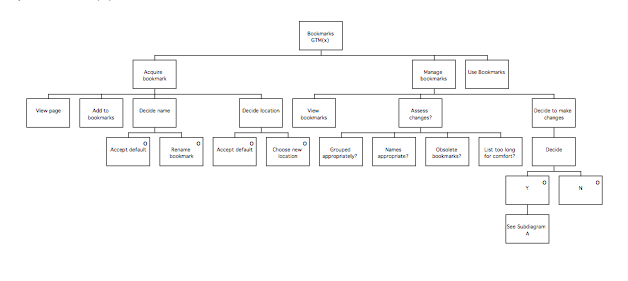

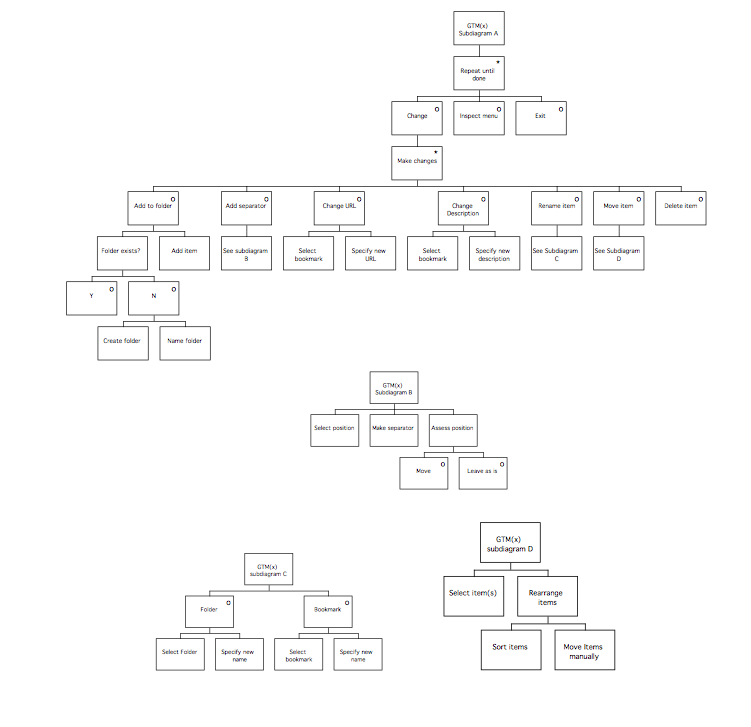

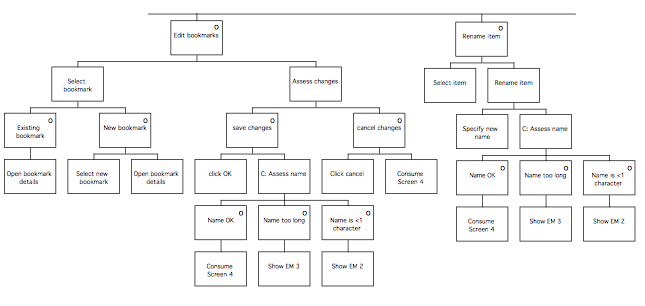

CTM(y) stage 115

Composite Task Model 116

CTM Table 117

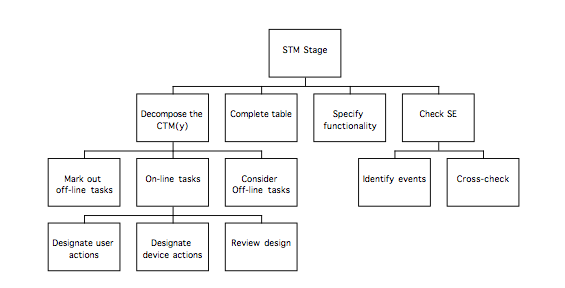

SUTaM stage 118

Extract from the STM 118

STM table 119

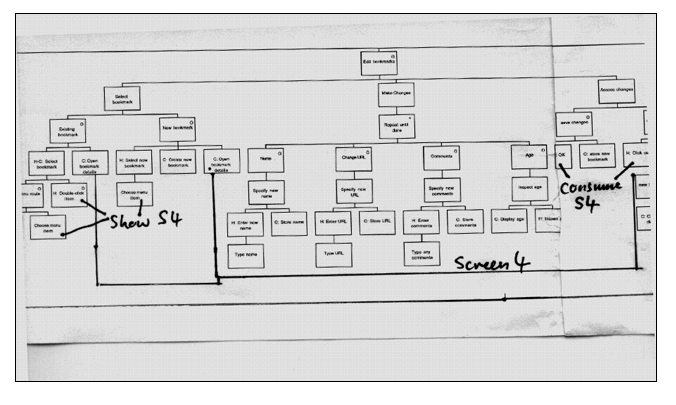

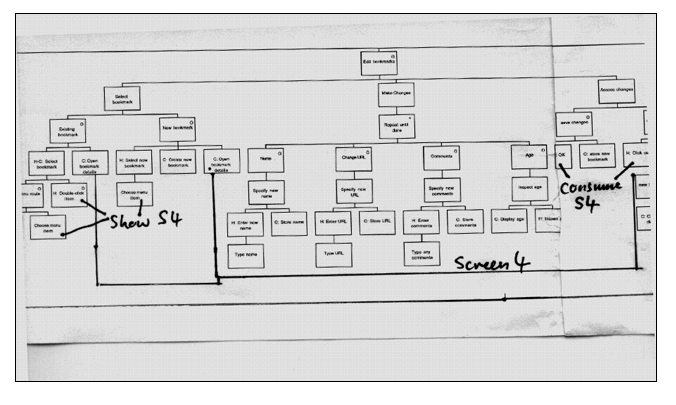

ITM(y) stage 120

Extract from the ITM 120

Decomposing the STM 121

ITM Table 122

Determining screen boundaries 123

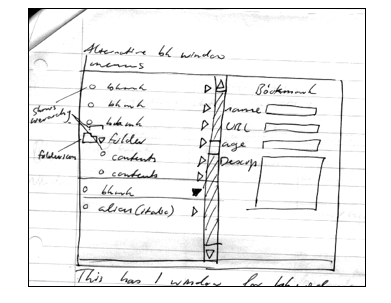

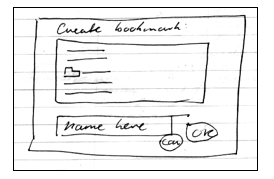

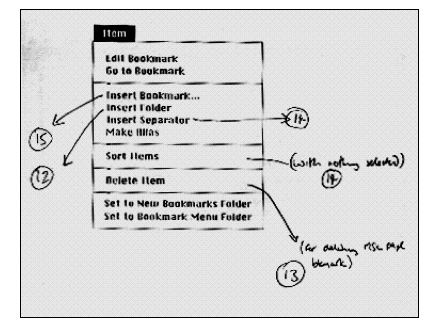

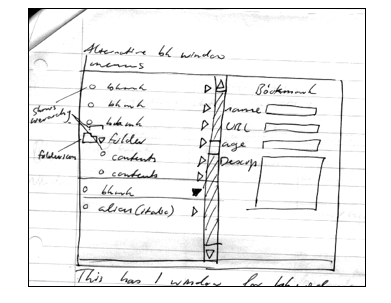

Display Design stage 125

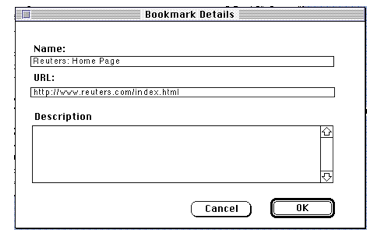

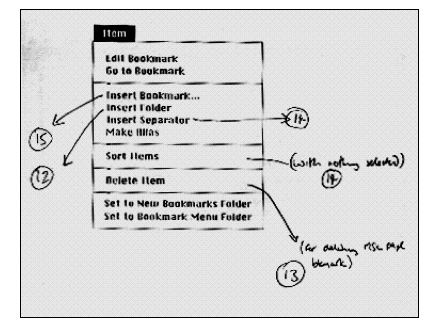

Pictorial screen layouts 125

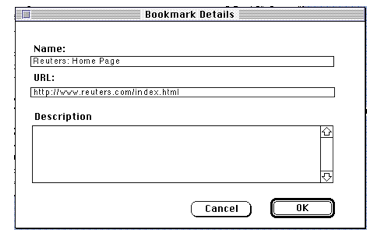

Dictionary of Screen Objects 126

Dialog and Error Message Table 127

Extract from the DITaSAD 127

Design Evaluation stage 128

Analytic evaluation 128

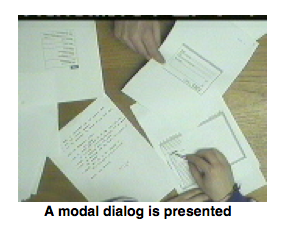

Empirical evaluation 128

Paper prototyping 129

Impact analysis 132

Rank ordering problems 133

Using iteration heuristics 133

Reviewing PLUME categories 134

The Ravden & Johnson Evaluation Checklist 135

Blank Tables 154

Task Description Table 155

Generalised Task Model Supporting Table 156

Statement of User Needs 157

DoDD(y) Supporting Table 163

Composite Task Model Supporting Table 164

System and User Task Model Supporting Table 165

Interaction Task Model Supporting Table 166

Dialog and Error Message Table 167

Dictionary of Screen Objects Table 168

Introduction to MUSE(SE)

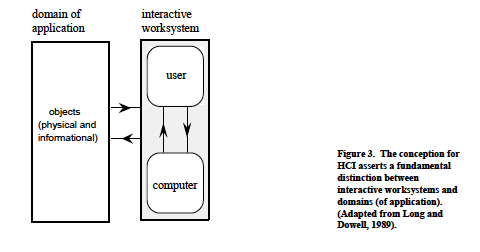

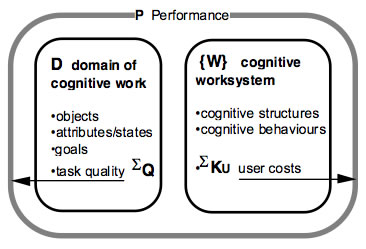

MUSE is a structured method for usability engineering. The method was developed to address the problem of Human Factors inputs to software design being ‘too-little-too-late’, where the input is mainly advice instead of specifications, and arrives too late in the process to be implemented. MUSE(SE) is an enhanced version of MUSE, intended for use by software engineers. Not only does it contain most of the knowledge needed to design effective user interfaces, it also contains procedures for checking the evolving design against the software engineering specifications. Although a certain amount of time must be devoted to MUSE(SE) during the early stages of a project, the benefits should justify the investment; the system should require fewer design iterations due to the user requirements being more clearly understood and the user interface having a better relationship to the requirements.

Many current Human Factors (HF) contributions to design are limited to a stage of design where the product developed by Software Engineers is available for usability assessment. Unhappily, this stage of design is one at which changes to the product may be prohibitively expensive. MUSE addresses this problem by specifying the user interface design process and the points at which HF and SE designs should be checked against each other.

The design of the user interface is approached ‘top-down’ based on information derived ‘bottom-up’. Design progresses in defined stages from specification of general features of the tasks to be performed (derived from analysis of the User Requirements and any existing systems) to specification of the specific details of the user interface to be implemented. The user of the method is provided with the techniques to apply at each stage, and any checklists or guidelines required by the method. Points at which certain features of the MUSE and SE design products should be cross-checked to ensure that the functionality specified in the software engineering design is compatible with that required by the user interface design is specified. Thus, the likelihood that the user interface under development will be implementable and provide the appropriate functionality to support the user’s task is maximised.

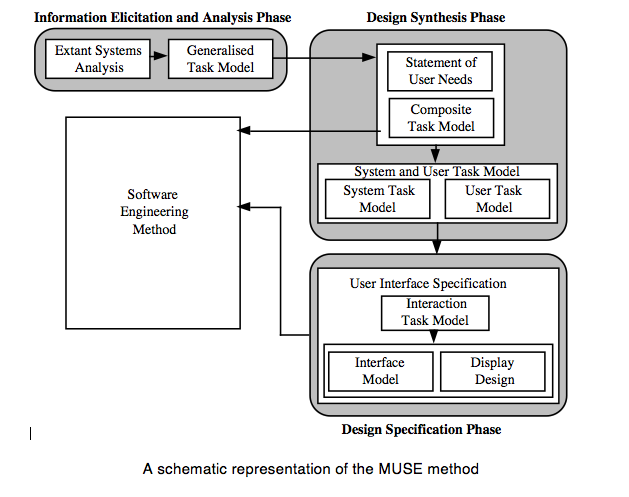

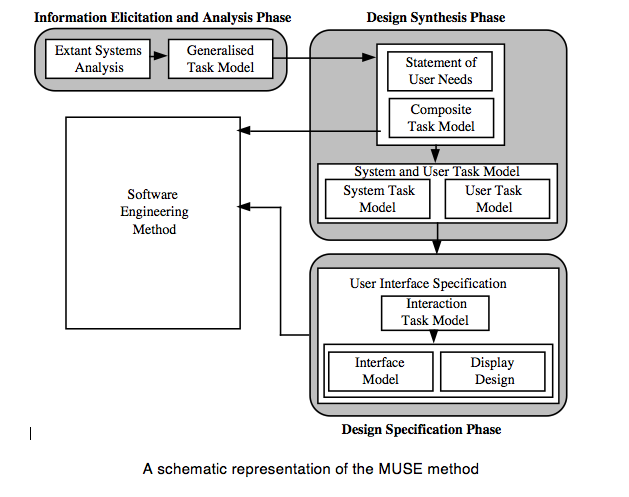

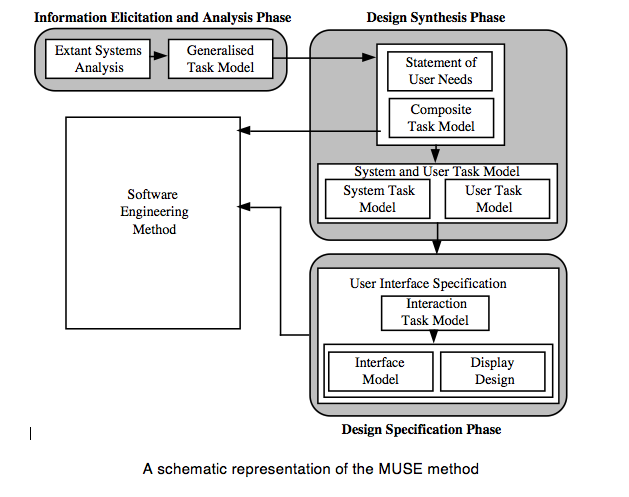

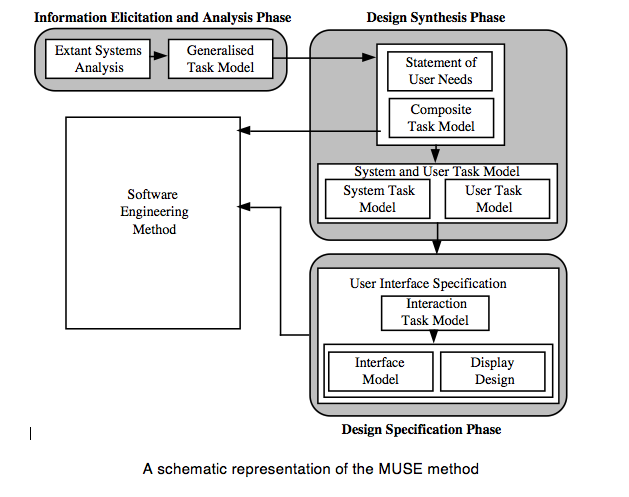

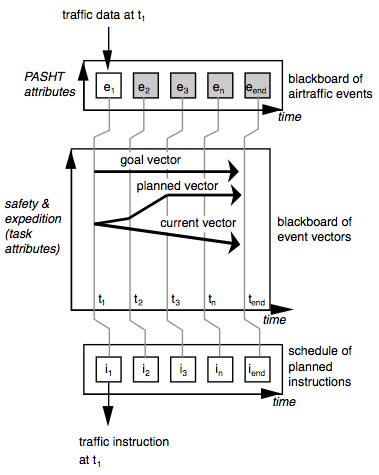

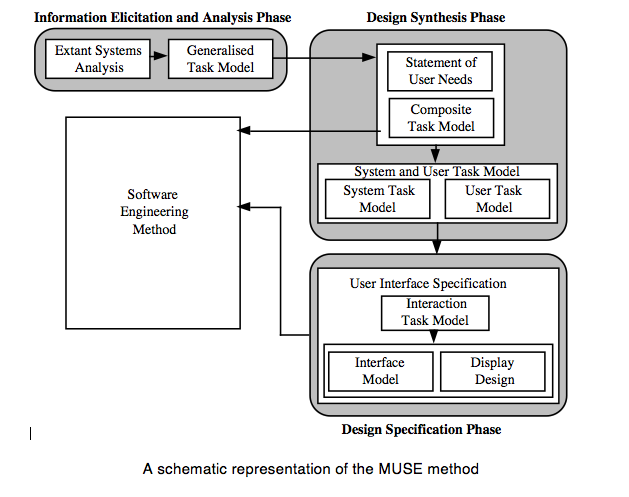

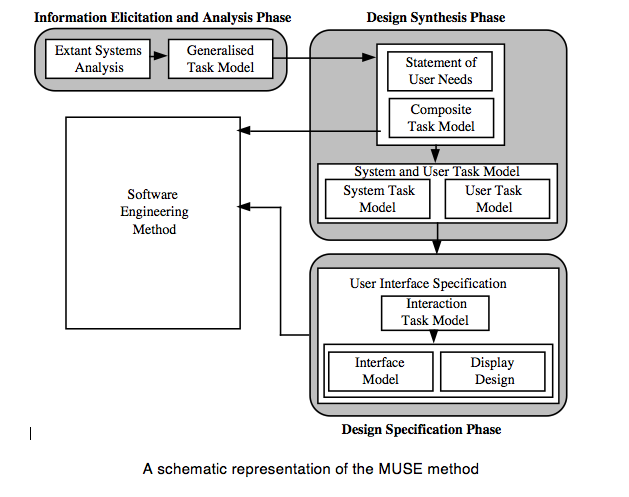

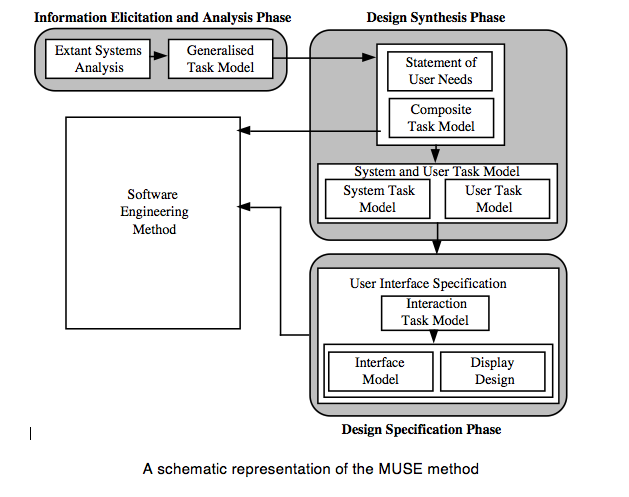

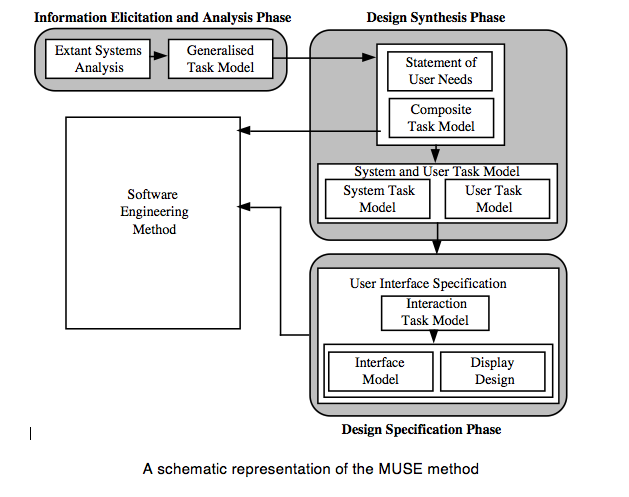

The diagram on the following page shows a schematic view of the MUSE method. A brief description of the method follows, outlining the three main phases of the method and the main products produced.

The first phase of the method is called the Information Elicitation and Analysis Phase. It involves collecting and analysing information intended to inform later design activities, and consists of two stages, the Extant Systems Analysis stage and the Generalised Task Model stage. During the Extant Systems Analysis stage background design information is collected that relates both to the system currently in use and to other systems that are related in some way, for example by having a similar task domain. The information concerns the users of the systems, the devices used and the tasks performed. The objective is to identify those features of the systems that are problematic for users, or that may provide good ideas suitable for re-use in the target system. During the Generalised Task Model stage, a device independent task model of the existing systems (GTM(x)) is generated using the task descriptions from the previous stage, and this is used in conjunction with the Statement of Requirements to produce a Generalised Task Model for the system to be designed (GTM(y)).

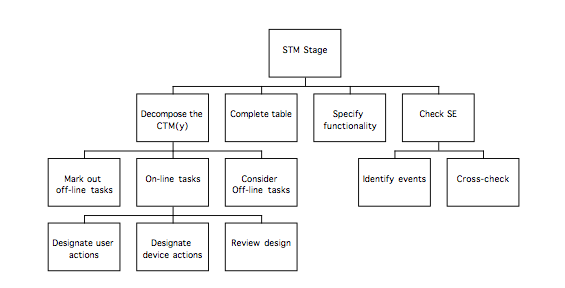

The second phase of MUSE , the design synthesis phase, begins by establishing the human factors requirements of the design, in terms of performance criteria, likely user problems or required task support, and these are recorded in the Statement of User Needs (SUN(y)). The semantics of the application domain as it relates to the worksystem are also analysed in this stage, and are recorded as a semantic network called the Domain of Design Discourse, or DoDD(y). The Composite Task Model (CTM) stage expresses the conceptual design of the target system, and is produced using the GTM(x) and the GTM(y). The process is informed by the SUN(y) and the DoDD(y) produced in the previous stage. The resulting design is checked against that of the software engineering stream, to ensure that the correct functionality will be provided. The conceptual design addresses error-free task performance only, in order to avoid obscuring the overall structure of the task.

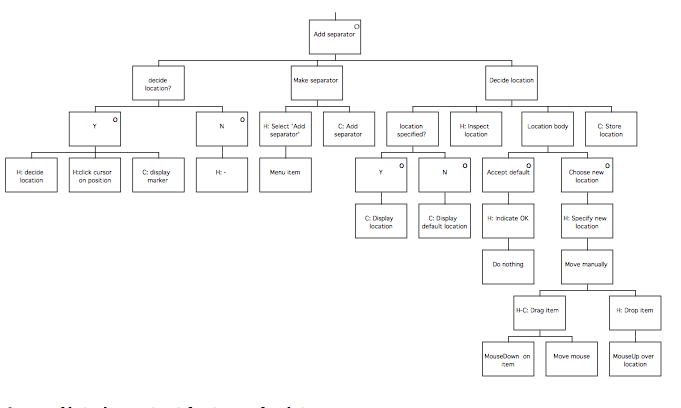

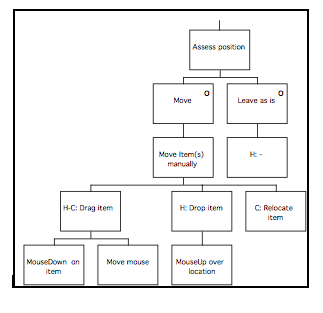

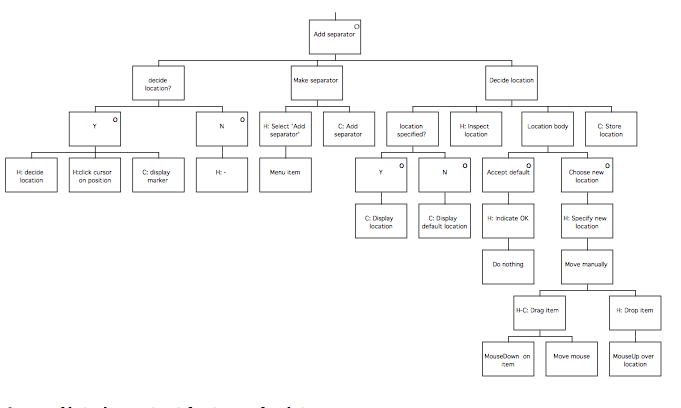

During the System and User Task Model stage, the Composite Task Model is decomposed to separate the subtasks that are to be performed using the system under development from those that are performed using other devices. The subtasks performed using the ‘target’ system are represented in the System Task Model, while the remaining (‘off-line’) tasks are represented in the User Task Model. Within the STM, allocation of function between user and computer is performed, and represented by designating actions as belonging to either ‘H’ (the user) or ‘C’ (the computer).

The final phase of MUSE is termed the Design Specification phase, and develops the conceptual design further to arrive at a device-specific implementable specification which includes error-recovery procedures. In the Interaction Task Model stage, the leaves of the STM representing user (‘H’) actions are decomposed further to produce a device-level specification of the interaction. This specification is mainly informed by the selected User Interface Environment, but the SUN(y) and DoDD(y) may also be used to further inform design decisions. The ITM(y) is annotated to indicate the locations of intended major screen transitions, which in practice are generally the boundaries of individual sub-tasks. During the Interface Model stage, the leaves of the STM(y) representing computer (‘C’) actions are decomposed to produce a set of Interface Models. These are detailed descriptions of the behaviours exhibited by screen objects, and the conditions that trigger them. In the Display Design stage, a set of Pictorial Screen Layouts (PSL(y)) are defined to correspond with the screen boundaries identified in the ITM(y). The interface objects that make up the screens are described in the Dictionary of Screen Objects (DSO(y)). A further product called the Display and Inter-Task Screen Actuation Diagram is produced, and details the conditions under which screen transitions may occur together with the conditions that would trigger the presentation of an error message. The error messages and dialogues are listed in the Dialogue and Error Message Table (DET).

Notations used in MUSE(SE)

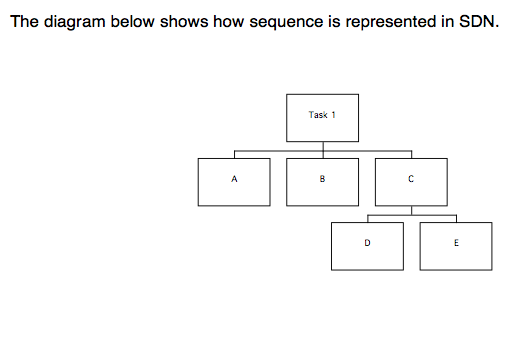

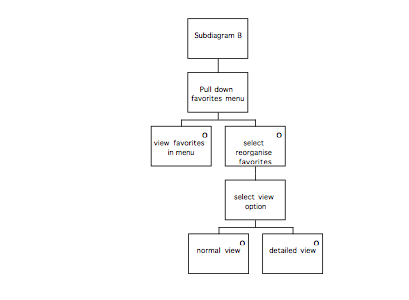

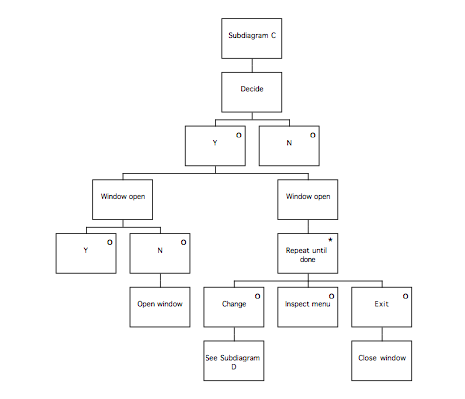

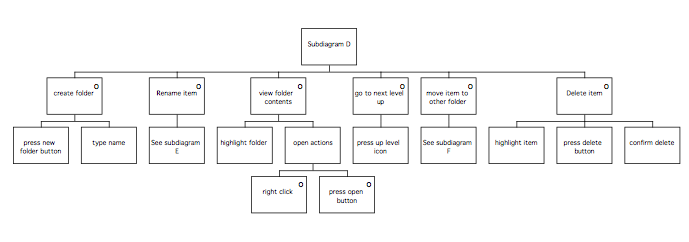

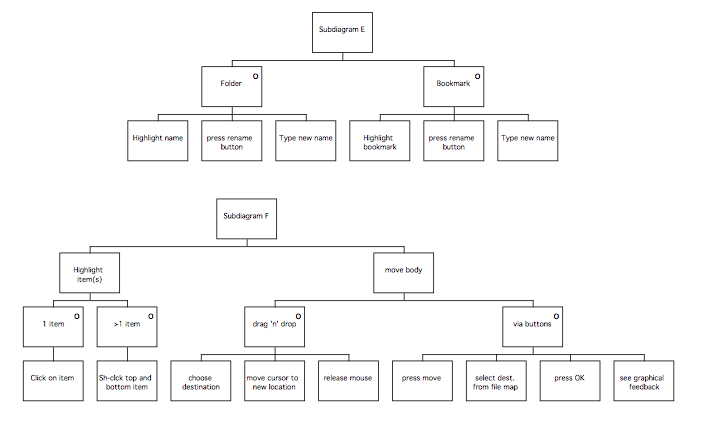

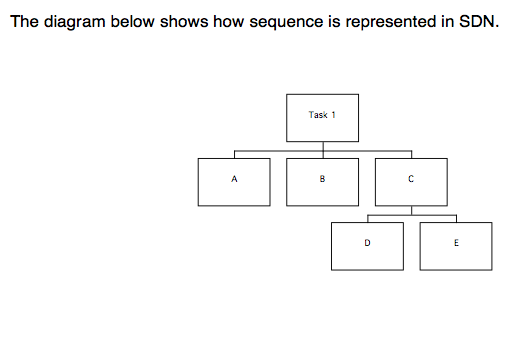

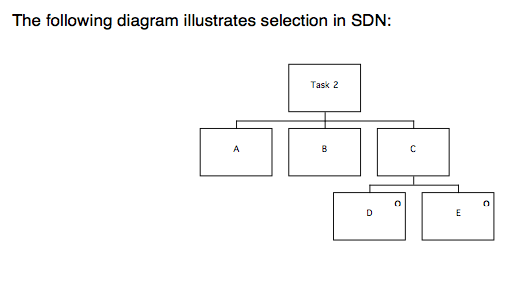

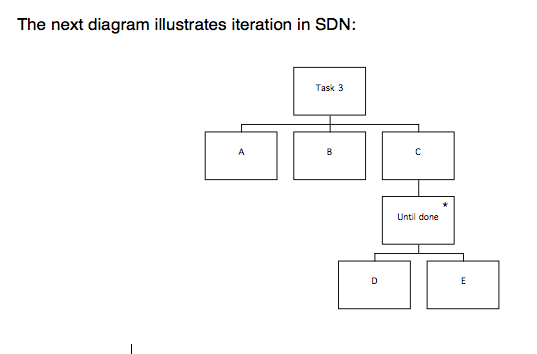

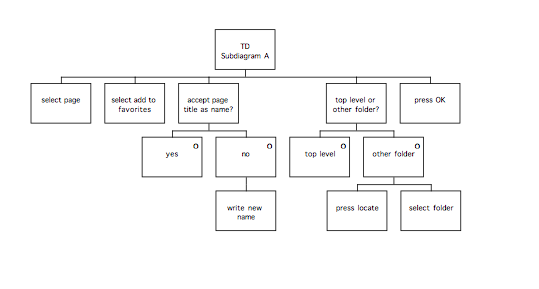

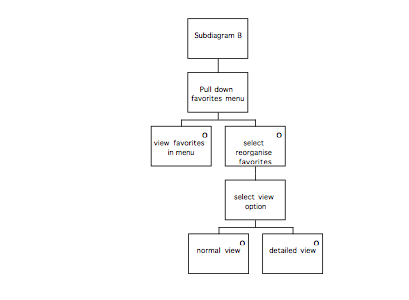

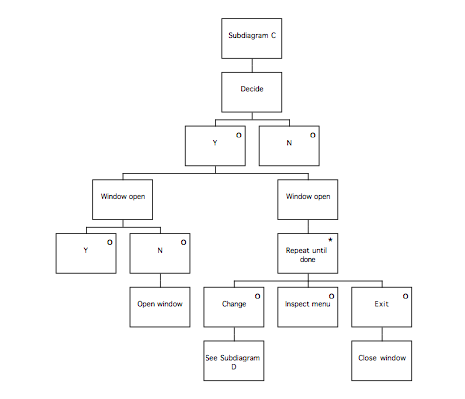

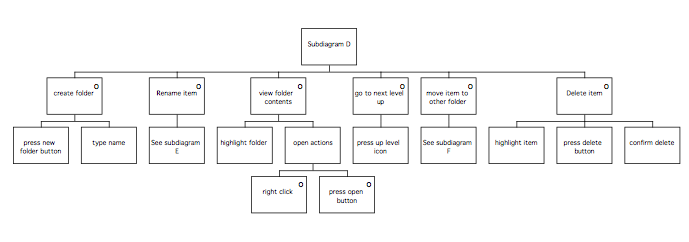

The main notation used by MUSE(SE) is Jackson Structure Diagram Notation (SDN). Some other notations are used during domain modelling, but these will be described in the course of the procedures.

SDN is a hierarchical notation used in MUSE(SE) for representing the structure of tasks and the behaviour of user interfaces. A supporting table is usually generated for each SDN diagram to provide additional detail; the recommended format of the table for each product will be given at the appropriate point in the procedures.

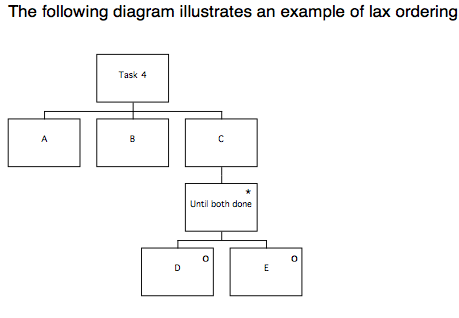

Task 1 consists of a sequence of A, B, and C. C consists of a sequence D, E. Task 1 is therefore a sequence A, B, D, E.

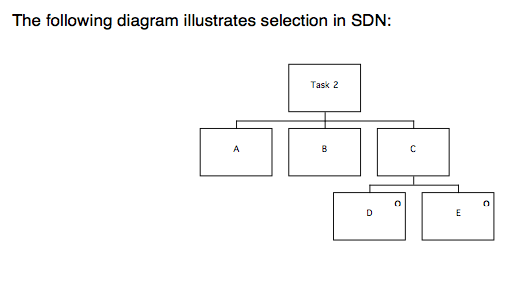

Task 2 also consists of a sequence A, B, C. However, C consists of a selection over D and E (indicated by the ‘o’; D and E describe the actions, but could be used to describe conditions with the ). Task 2 therefore consists of either A, B, D, or A, B, E.

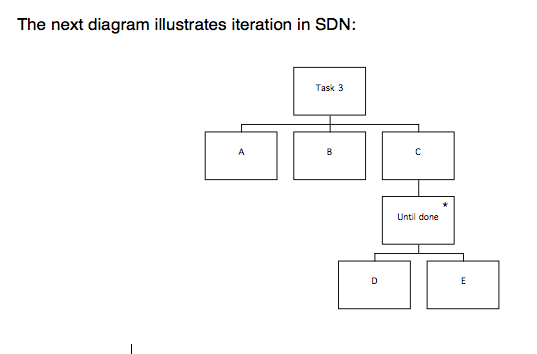

Once again, the task consists of a sequence A, B, C. C consists of an iteration of D and E (indicated by the ‘*’), which is repeated until the user is ready to stop. Task 3 consists of a sequence such as A, B, D, E, D, E, D, E.

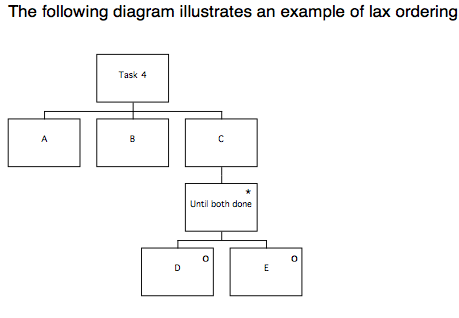

Finally, combinations of constructs can be used to represent more complicated behaviours. The most useful of these is lax ordering, where parts of a task can be completed in any order.

Task 4 consists of a sequence A, B, C, as before. This time, C consists of an iteration over a selection between D and E. Depending on the conditions applicable to the iteration and selection, this construct can represent an instance where neither D or E are performed, either of D or E is performed one or more times, or a sequence D, E or E, D is performed one or more times. In the case of Task 4, the sequence of events could be any of A B E D, A B E E D, or A B D E, because the condition on the iteration is ‘until both done’.

Note: MUSE(SE) uses SDN in a fairly informal manner to describe behaviours of the user. As a result, diagrams can sometimes contain ambiguities, and this is one reason why it is important that supporting tables are used to provide additional information about the diagrams.

MUSE(SE) Procedures

Introduction

The next section of this document describes the procedures for MUSE(SE). Before you start, you should understand how to draw the SDN diagrams used in MUSE(SE), and you should have a basic understanding of the purpose of each of the MUSE products. Refer to the example after the procedures if you need to see what a product should look like.

Each section of the document contains a summary of the procedures for a phase or stage of MUSE(SE), followed by the detailed procedures. Some stages are provided with a set of heuristics, or ‘rules of thumb’ after the procedures; these have been selected because they offer guidance that may be relevant at that point in the method. Several of the heuristics are included more than once; this is because they are relevant at more than one point in the method.

Within the detailed procedures, procedures in bold are described in more detail afterwards; where this involves several steps to be followed, they are listed either as bullet points or as sub-procedures, e.g. 1a, 1b, etc. Procedures in plain text are not described further, but may be followed by commentary.

Every so often there is an ‘OMT cross-checking point’. If you are working in a team, then you should arrange to meet with the person responsible for the OMT products at these points to compare designs. If you are working on your own, then you should update your OMT products at these points, using the cross-checking procedures to indicate the MUSE(SE) products that should be used to inform the development of the OMT products[1]. If it turns out that it isn’t possible to make the OMT products agree with the MUSE(SE) products, the cross-checking procedures can be used to determine which MUSE(SE) products will need to be amended.

Where you see a note like this, in square brackets:

[Refer to xxx]

…it means you have to refer to another document, which will be included at the back of the procedures. Note that proformas for all of the tables required by the method are also included at the back of the procedures so that they can be photocopied and used for making handwritten notes during the design process. Do not be tempted to omit completion of the tables supporting each product. The tables are at least as important to the design process as the diagrams, because they contain the design rationale.

Every so often there is a table like the one below for you to rate the procedures you have just followed. If a particular procedure causes difficulty, please make a note of it so that you remember to record it in the comments section of the table. (Documents referred to in the square bracketed comments should be treated as part of the procedures).

The table asks you to rate each section of the method according to how ‘coherent’ and ‘complete’ you found the procedures, and to rate the extent to which the procedures ‘concerned what was desired’. You are also asked to record how long each stage took (in person hours, or days). Coherent refers to how understandable the procedures were; if they made little sense, then you would disagree with the statement that they were coherent, whereas if they were perfectly clear then you would agree. The completeness of the procedures refers to whether or not they seemed to miss anything out; you would disagree with the statement that they were complete if you had to work out what to do yourself because the procedures were insufficiently detailed, or if you had to refer to guidelines that weren’t mentioned in the method. The extent to which the procedures ‘concern what is desired’ refers to how relevant you felt they were to the MUSE design process; if the procedures were clear and detailed, but still didn’t enable you to produce the appropriate design product, then you would disagree that they concerned what was desired. The space at the bottom of the table is provided for your comments on your answers, or on other aspects of the stage.

| Example Rating table

Please rate the above procedures according to the extent they fit the descriptions in the left hand column

|

| |

Agree strongly |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Disagree Strongly |

Coherent

(i.e. understandable) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

| Complete

(i.e. there was nothing missing) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

| Concerned what was desired

(i.e. did the procedures allow you to do what you were supposed to?) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

|

Time taken:

|

Diagrams |

Tables |

Revision |

Other (specify) |

|

Further

Comments:

|

* Please describe what the problem was |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Phase 1

Information Elicitation and Analysis

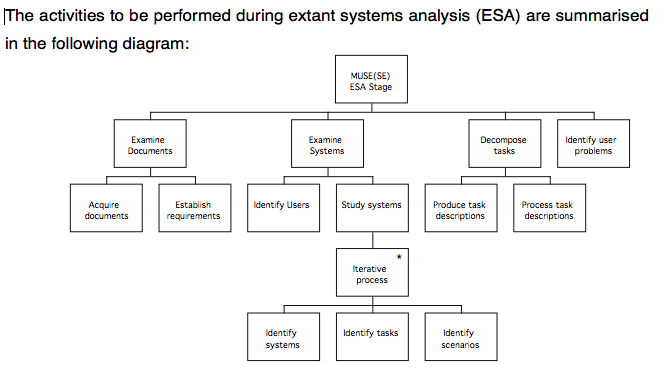

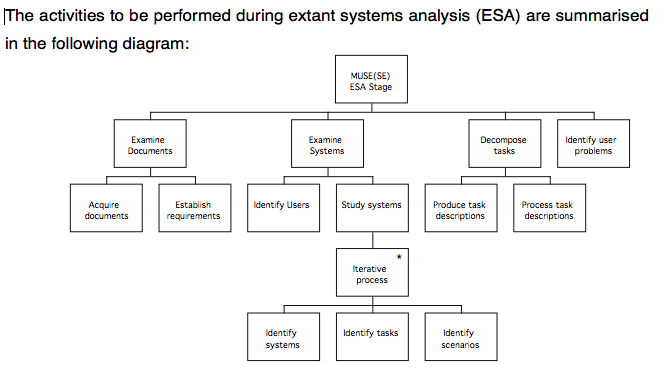

MUSE(SE) Phase 1 Procedures: Extant Systems Analysis Stage

These steps involve applying some techniques to elicit the information, which are summarised below.

The detailed procedures on the following pages will describe how to carry out each of these steps:

- Examine Documents: Obtain the statement of requirements

Establish the requirements

- Examine the systems: Identify Users

Identify Systems

Identify Tasks

Identify circumstances of use

2.1 Familiarise investigator with the system to find out how it works by: Observational studies

Task execution

2.2 Interview user representatives to obtain problems and task objects using:

Card sorting

Structured interviews

2.3 Record findings of 2.1 as preliminary TD products, and separate those of 2.2 into problems and domain information

2.4 Construct ‘typical’ tasks for use during testing.

2.5 Study the systems using:

Informal / Observational studies / Usability tests

Concurrent verbal protocol

Task execution

PLUME, Guidelines and heuristics

Checklist

- Decompose tasks to: produce TD(ext)

process TD(ext) into GTM(ext

- Identify usability requirements

Detailed procedures

The following paragraphs provide detailed procedures describing the information to be gathered during each of the steps in the analysis stage, and also describe how to record the information in the appropriate MUSE(SE) product for later reference.

It is recommended that you read the procedures through before performing them, so that you can plan each stage. It is assumed that a project plan has been produced; this should be consulted to obtain details of how quality control is to be addressed, and the number and scope of any planned design iterations. The effort allocated to each stage of the method should be noted so that it can be reflected in the detailed plans for each stage of the method. Access to users should be arranged as early as possible in the project, and a file should be opened to store the products of each stage of the method.

The procedures for steps 1 to 5 will now be discussed in detail.

- Examine Documents: Obtain the statement of requirements

Establish the requirements

The statement of requirements should be obtained, and reviewed in order to gain an understanding of what the target system will be required to do, in terms of the functionality that the system will have, and the types of tasks it will support. The requirements document will need to be consulted during the course of design, so it should be filed with the MUSE(SE) design documents for reference.

- Examine the systems: Identify Users

Identify Systems

Identify Tasks

Identify circumstances of use

Identifying the users

The following information concerning the users of the system should be obtained, by asking the ‘client’, by consulting user representatives, or by conducting a straw poll of users. If there are a number of different groups who will use the system, then the information should be collected for each group. If the user group is expected to contain a lot of variation within any or all of the categories, then you should make a note of this and attempt to estimate the most likely range of variation.

Number of users

Type of users

Experience level

Computer skills

Other systems used (now)

Education level

Tasks Performed using system

Age

Sex

Any other information that may be relevant should also be noted

Identifying the tasks

The following aspects of the task the system is intended to support should be noted:

Who does the task

Task goals

Frequency

Duration

How often errors occur, and how critical this is

What subtasks there are

Identifying the circumstances in which the system is used

An understanding should be gained of the circumstances surrounding use of the system; whether it is used once a week or every five minutes; whether using the system is considered enjoyable or a chore, and whether the users can choose whether or not to use the system. Any other observations of this kind should also be noted.

Use Pattern

Frequency of use

Motivation for use: what the system means to the users

Whether use is mandatory or discretionary

These preliminary notes should be treated as forming part of the statement of user needs, which will be constructed later in the method following detailed analysis.

2.1 Familiarise investigator with the system by:

Observational studies

Task execution

Select systems to examine based on the task that the target system is required to support. The current system is always selected, and similar systems can be selected as well if they appear likely to prove informative. (You might want to pick the related systems after examining the current system. Only the relevant parts of related systems are analysed, and only to the level of detail that is likely to be informative).

To determine which related systems should be examined, the Statement of Requirements should be examined. By considering the key characteristics of the system (i.e. what general type of system it is), together with any relevant constraints, it should be possible to produce a list of systems which have something in common with it from the user’s point of view. Systems that involve doing a similar sort of task, or which impose similar constraints on the user are the most likely to provide good design ideas.

Once you have a list of candidate systems, select which ones to examine bearing in mind the time available and the ease with which access can be arranged. It is suggested that at least three systems are chosen: the current system, the ‘next best’ system, or the closest available alternative, and a system where users do a similar task, but which either works well from the users point of view or presents similar problems (this might provide insight into the cause of the problems).

Following selection of systems, informally observe users performing the tasks to obtain information as follows:

The main tasks the users have to achieve

Whether these tasks have any subtasks

The main behaviours of the user and the computer when performing the tasks

How the behaviours are decomposed in relation to the tasks and over time

The work domain objects, their attributes, values, and properties (methods)

The investigator performs the task, to assess likely levels of:

User costs: How difficult the system is to learn, i.e. training requirements,

How much physical effort is needed to use the system, i.e. fatigue and physical effort involved

How much mental effort is needed to use the system, i.e. costs of mental fatigue, correcting errors, and time taken to perform task

Device costs Structural i.e. wear and tear on device, such as repetitive key operations

Resource costs i.e. processor use

(This evaluation of costs should be used to flag areas for later investigation, following greater familiarisation with the device. Resource costs incurred by the device are of relevance only in circumstances where they are likely to constrain the solution, for example where a very slow processor is being used or memory is severely limited).

Whilst performing the task and experimenting with the device, you should seek to understand the functionality and structure of the device. This is not necessarily equivalent to gaining knowledge of the structure of the task or the subtasks, because the device may not support the user’s task very well at all, and will frequently have surplus or inappropriate functionality. Whilst examining the user interface, try to identify the main objects that are presented to the user and what their properties appear to be. You will need these before you interview the users, so now would be a good time to read procedures for the following step (2.2).

Don’t attempt to construct TD products based solely on experimentation with the device, as this can lead to replicating the problems of the existing system in the new design. Information about the structure of the task obtained by this means must be regarded as unreliable until validated by observation of real users, but is nonetheless a very useful preliminary activity .

To continue the process of familiarising the investigator with the system before user testing commences, a small number of users should be interviewed:

2.2 Interview user representatives to obtain problems and task objects using: Card sorting

Structured interviews

The investigator interviews a small number of representative users (about 2 or 3 should be sufficient, or enough to get a cross section of the users if the user group is very varied). The objective of the interview is to obtain more information on the main tasks that are carried out using the system, and what the semantics of these tasks are (i.e. what the task involves, at a fairly high level – without going into the details of using the device, because this will be studied by direct observation). The investigator should also find out whether the users think that there are any problems with the task as it is currently performed. The investigator should then discuss the task with the users to discover the main objects that are transformed during the task, and any other entities involved; as well as finding out the attributes that get transformed, the properties of the objects and the rules concerning them should be elicited.

Cards are prepared for each of the objects identified during the initial familiarisation of the investigator with the system. Each card will contain the name of the object together with the attributes, values and properties (i.e. methods) previously identified; spare blank cards should be provided for new objects or relationships uncovered during the interview. The objects should have abstract attributes as well as physical (i.e. ‘safe’, ‘unsafe’, ‘urgent’, ‘done’ or ‘ready’). These cards are used during the interview to help elicit further information about the objects by correcting the descriptions, sorting the cards into groups, and naming or relating the groups with the extra cards provided; this is described in more detail on the next page. A whiteboard and some Post-It notes should be obtained before the interview starts.

The users are interviewed (with the system present) to obtain information on:

- The goals of the task in terms of the objects and attributes transformed

- The main IWS behaviours performed (i.e. task and semantic level behaviours)

- The user’s mental processes and representations

- Particular problems experienced

- The work domain objects, and their attributes, etc.

Arrange access to a number of users (ensure enough are interviewed to represent a good cross-section of the user group for the target system) so that you can interview them with the system present. Video or audio recording the interviews may help with later analysis, and it would be useful to have a whiteboard available.

- Begin by introducing yourself and telling them the purpose of the discussion. Let them know that they’re the expert on their job, and you’re designing a system to help them do it better, so you need their input. It’s important that they don’t feel you’re there to evaluate them and they realise it’s the system that’s under scrutiny. Say you’re interested in what their job involves (i.e. the main tasks), the entities that get modified by the task or that have a bearing on the tasks, the way they actually do their job, and where and how the current system supports the job; the idea is for them to help you to determine whether the new system would benefit from any modifications, or whether it should be like the old one. Explain that you’re going to draw a diagram to show the structure of their task, a list of good and bad features of the system, and a ‘mind-map’ diagram to illustrate the rules that they need to know to do the task and how they think about the properties of the ‘objects’ involved.

- Get them to describe briefly and in general terms the tasks that they do, which of them they use the system to support, and what the general goals of the tasks are. Make a list of the tasks, and note any potential objects they mention whilst they are speaking. Check if the tasks must be performed in any set order, and make a note of this. List the goals of the tasks.

- Sketch an initial task description diagram. The top node should describe the overall diagram, i.e. ‘Widget stock controller’s tasks’. The top row of the task model should consist of the main tasks that they mentioned, i.e. ‘Check stock levels’, ‘Establish widget requirements’, ‘Generate orders’, ‘Process a delivery’, ‘Notify accounts department’, ‘Update stock levels’. Make sure that the diagram reflects any constraints on the ordering of the tasks. Lead them through the diagram, explaining the notation, and ask them if it’s correct. If it isn’t, change it so it is. Now mark the tasks that they use the system to support, and ask them to show you how they would perform each task.

- Start a new diagram for each task, labelling it to agree with the corresponding node on the main diagram. Ask them to demonstrate the task bit by bit, so that you can start to decompose the task description, carrying the decomposition down to a level where the diagram would be sufficient to enable someone else to perform the task. As they go, ask them to point out where they find the task problematic; note the problems so that you can record them in the tables later on. Make a note of any new objects or attributes that are revealed whilst they demonstrate the task. Show them the task description, and ask them whether it describes the way they would normally do the task, and if it’s incomplete or incorrect in any way. Continue until the whole task is documented as a task description diagram.

- Write the name of each object and entity on the cards onto a Post-It, and stick the Post-Its to the white board. With the user’s help, arrange them on the whiteboard so that the relationships between them can be indicated by connecting lines, and annotate the diagram to indicate what the relationships are, as in an entity-relationship diagram. Continue until the user is happy that the diagram is complete and reflects their view of the task. (Remember that you’re trying to elicit the user’s view of the task domain at this point; you’re not trying to construct the software engineering object model (or even necessarily a ‘correct’ entity-relationship diagram), so it doesn’t matter if there are some objects that you won’t be implementing, some that will need to be decomposed further when the system design progresses, of if the relationships in the model are more like the methods of some of the objects. The attributes of the objects will probably inform the SE model, even if the objects themselves are differently organised, as will the ‘methods’).

- Copy the completed model onto paper so that you can refer to it later when the MUSE(SE) DoDD(y) is produced. Any additional attributes or methods discovered should be added to the appropriate card, and any new objects discovered should be recorded.

The interviewer should aim to find out whether the categories of information above are completely represented, perhaps by getting the users to think of exceptions that aren’t covered.

2.3 Record findings of 2.1 as preliminary TD(ext) products, and separate those of 2.2 into behaviours and domain information

The goals of the task are used with the information about behaviours gathered from the interview to form the top level of a preliminary TD(ext). The IWS behaviours and decomposition information from the observation and interview is added to complete the initial structured diagrams.

Use the task descriptions from the interviews to derive a single model for each system studied that describes the behaviour of the users observed, showing where choices exist or alternative orders can be used for performing the task. It may be possible to base this on the most complete model from the interviews conducted about each system; alternatively, you will need to build the model up based on several interviews.

A table like the one shown below should be prepared for each diagram, and any notes about the diagram entered into the cells. The tables can be referred to later in the design process, to avoid losing ideas or observations.

| Name |

Description |

Observation |

Design

Implication |

Speculation |

| Which cell is referred to |

Further description as necessary |

Any notes |

Any implications, based on ESA work |

Any design speculations occurring at this stage |

The information from the interview concerning the user mental behaviours is used to elaborate the appropriate points in the diagram. The information on mental representations from the interview should be filed for later inclusion into the DoDD(y). The information concerning costs from the task performance by the investigator can be used to prime collection of information during usability tests by suggesting particular things to look out for, as should the user problems discussed during the interview. Where differences existed in the order of task performance between individuals, this indicates that the task is lax ordered and the fact should be noted in the table and recorded in the SUN when it is produced later in the method. Using the TD(ext), it should be possible to follow the sequence of the contributing TDs; where it is not possible to do so, this must be noted in the table and recorded in the SUN when it is produced later in the method so that the Composite Task Model can be checked to ensure that the problem has not been ported along with the high level structure of a TD(ext).

2.4 Construct ‘typical’ tasks to be used during testing.

Information from the preliminary TD(ext) and the other procedures above is used to construct realistic examples of tasks for the users to perform whilst the investigator records them. The tasks can be used to obtain more information about potential user problems noted earlier, by designing them in such a way that the user is likely to encounter the problem as they do the task. The descriptions of the tasks should not dictate the manner of task execution, only the task to be achieved by the users and sufficient contextual information to give the task meaning. (For example: ‘You need to email a Word document to x, who works at y; you know they use a PC, but you’ve no idea what word processor they have’). Before using the tasks for testing, they should be checked with a user representative to ensure that they are realistic. As well as constructing sufficient tasks for current testing needs, some should be prepared ready for testing the design at the end of the method (if possible, use different tasks for testing now and at the end of the method; this will provide greater confidence that the design supports the full range of tasks, not just the instances that were studied in detail).

2.5 Study the systems using:

Informal / Observational studies / Usability tests

Concurrent verbal protocol

Task execution

PLUME, Guidelines and heuristics

More than one user should be studied for each system that is to be examined, whether related or current. You should make sure you have your preliminary task description for the relevant system available, and that a notepad is handy to write down any additional observations.

Recruit some typical users to use the system whilst you observe them. If possible, the session should be recorded on video (or at least audio tape, if a video camera is not available). Make sure the user understands that it is the system that is being evaluated and not them.

Provide each user with one of the descriptions of typical tasks that were generated in the previous step. Ask them to perform the task described as they usually would, but tell them that it’s not a test and you’ll help them if they get into difficulties; whilst they are doing the task, ask them provide a running commentary describing what they are thinking about and any assumptions they are making about the task or the system. You may find you need to remind the user to keep their commentary going from time to time, particularly if they start getting into difficulty. If they get into severe difficulties, it may be necessary to give them a hint, or even to stop the trial and discuss the problem.

Observe the users performing the task to uncover any mistakes or incompleteness in the TD(ext); where found, these should be noted. Video (or at least audio) recordings of the subjects should be made wherever possible, to support later analysis of interesting events or things that happened too quickly to be noted in real-time. New domain objects or attributes that are observed are also noted for the DoDD(y). User problems or errors noted during the test are noted, so that they can be investigated further in later trials, and recorded in the Statement of User Needs when it is constructed.

The verbal protocol is used to annotate the TD(ext) product with the mental processes of the user, as are the user problems, errors, and performance shortfalls. The notes made during observation of users should be written up in the tables for the TD(ext) product so that they will not be forgotten later in the design.

The notes gathered in this stage also form an input to the Statement of User Needs. As much as possible, group the problems according to which of the following categories they appear to concern most directly:

Productivity

Learnability

User satisfaction

Memorability

Errors

These categories are known as the PLUME categories, and will be revisited later in the method when the Statement of User Needs is produced.

Users’ mental representations (i.e. the notions they have about objects, their properties and the rules for manipulating them) should be noted for use during construction of the Domain of Design Discourse product (DoDD(y)).

[Obtain a copy of the Ravden and Johnson checklist, which is reproduced at the back of these procedures]

Finally, the investigator uses the system once again, this time employing the Ravden and Johnson checklist. In addition, a styleguide and any relevant guidelines or heuristics may be used to assess the device, paying particular attention to areas where errors were noted under PLUME categories, with the goal of diagnosing the source of the problem. The information resulting from this is used to annotate the TD(ext), and filed ready for inclusion in SUN(y). If the user’s workstation is to be redesigned, it should be assessed against an appropriate set of guidelines such as those found in the US MIL-STD or the EC Directive; relevant findings from this assessment may be used to annotate the TD, and should be filed for inclusion in the SUN along with an assessment of any relevant user physical limitations, also derived from guidelines or standards.

Repeat procedures 2.1, 2.3, and 2.5 for any related systems identified.

- Decompose tasks to: produce TD(ext)

process TD(ext)

The information from the second set of observational studies (step 2.5) is used to complete the TD(ext), which should be constructed following the above procedures for the preliminary TD(ext) given in steps 2.2 and 2.3.

The TD(ext) table should now be completed further with the evaluation information on behaviours from the observational studies, and the information on mental processes gained in the interviews and from the card sorting and protocol activities. The tables are also annotated with information on the quality of task performance (i.e. how well the users were able to achieve the task) from the usability testing and domain objects from observation, interviews, and card sorting. The TD(ext) is then summarised and abstracted to a device independent level to form the GTM(ext); GTM(ext) production will be discussed as part of the GTM stage.

- Identify usability requirements

At this point, identification of the usability requirements can be performed, and acceptable levels for productivity, learnability, user satisfaction, memorability and errors should be decided. A means of determining the acceptability of these properties should be decided, and the they should be prioritised and recorded. The styleguide that the target design will be expected to follow should be selected at this stage, and this should be noted as one of the usability requirements.

OMT Cross-Checking Point:

Refer to the Use Cases and scenarios generated as part of the OMT process, and carry out the following checks, considering the models as a whole in both cases.

- Make sure that user and device actions (and device semantics) documented in the TD products are described correctly in the use cases and scenarios (to the extent that these are likely to remain unchanged in the new system; it’s more important that the models do not contradict each other rather than that they are identical).

- Make sure that domain objects and their attributes documented in the task descriptions are correctly described in the use cases and scenarios (to the extent that they are likely to remain unchanged in the new system), particularly where user inputs are concerned.

| ESA Rating table

Please rate the above procedures according to the extent they fit the descriptions in the left hand column

|

| |

Agree strongly |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Disagree Strongly |

Coherent

(i.e. understandable) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

| Complete

(i.e. there was nothing missing) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

| Concerned what was desired

(i.e. did the procedures allow you to do what you were supposed to?) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

|

Time taken:

|

Diagrams |

Tables |

Revision |

Other (specify) |

|

Further

Comments:

|

* Please describe what the problem was |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MUSE(SE) Phase 1 Procedures: GTM stage

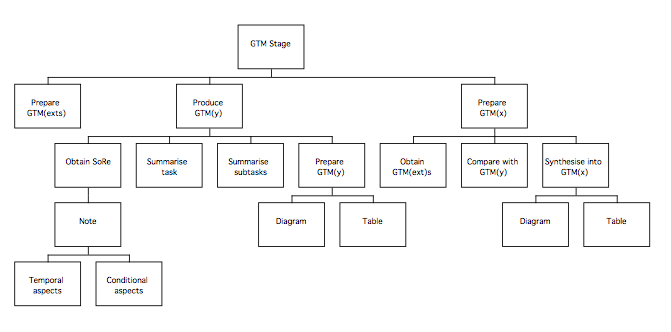

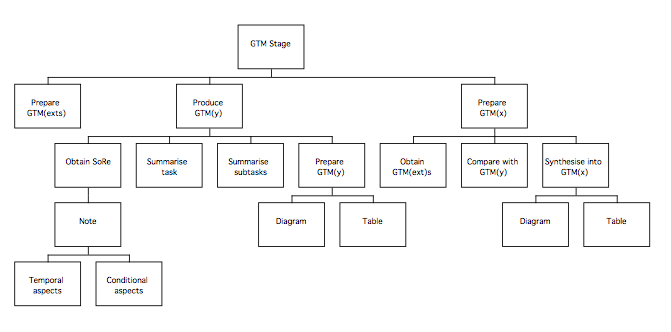

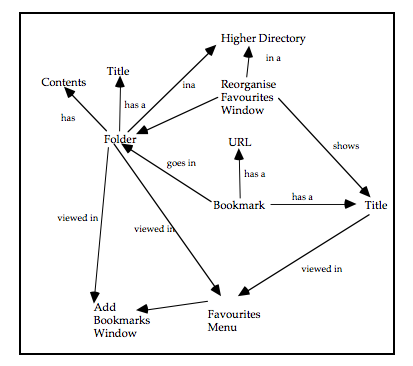

Following Extant Systems analysis, the next stage of the method involves abstracting from the task models generated from each system studied (the TD(ext)s) to produce a device independent view of each system called a Generalised Task Model, or GTM(ext). These models are then combined to result in one that describes all the features of interest of the current systems, called the GTM(x). A similar model (GTM(y)) will be produced of the target system, based on the statement of requirements for the purposes of comparison. The following diagram summarises the stage.

Generifying tasks to produce GTM(ext)s

Generification involves raising the level of description of the tasks so that they are device independent and can be compared with each other more easily. A GTM(ext) represents the manner in which tasks are currently performed, so one GTM(ext) is required for each type of task studied (i.e. if related tasks were examined, each requires a GTM(ext)). Frequently, much of the work of producing a GTM(ext) involves summarising the lowest levels of description and making sure that terms are used consistently both within and between diagrams. Where this is made difficult by a large or complicated task description, the following procedures can be used:

- List out the objects and actions

- Eliminate redundant items (so each item is listed once)

- Group the terms that appear similar

- Name each group (the group names can be validated by showing them to users, or the users could help with the grouping process if this is convenient)

- Reconstruct the model, using the generic terms

- Validate the model by asking users if it is a description of the original task

Some rules of thumb to be borne in mind when preparing GTM(x) and GTM(y) are presented on the next two pages, followed by the procedures for production of the GTM(x) and GTM(y).

GTM Heuristics

Consistency:

The GTMs need to be internally consistent:

- Use terminology consistently; make sure that descriptions of objects or actions don’t change within, or between, the GTMs.

- Comparable operations should be activated in the same way, and should work in the same way everywhere.

…but also need to be consistent with the user’s knowledge of the task, so that users will be able to see what they can do and what state the machine is in at any point…

- Object names mentioned in the GTM should be concrete and recognisable

- Use the same word to describe actions (functions) that seem similar to the user

- When using metaphors, ensure properties of objects are appropriate

The target system should also be consistent with other applications…

- Follow conventions for the environment, so users can reuse knowledge from elsewhere

- Use terminology that is consistent with the styleguide; be careful about using words which are the names or system objects (or menus), unless you are really referring to them.

Simplicity:

Remember that the aim is to design an interface that will be simple, easy to learn, and easy to use; users shouldn’t be surprised by the behaviour of the system.

Promote simplicity by using the following rules of thumb:

- Remember that maximising functionality works against maintaining simplicity.

- Reduce the number and complexity of necessary actions to a minimum;

- Reduce presentation of information to the minimum needed to communicate adequately.

- Disclose information to the user progressively to they only see it at the appropriate time.

- Use natural mappings and semantics in the design.

- Use verbs in the GTM to describe actions (e.g. ‘sort items’ instead of ‘sorter’; avoid describing components of the system when it would be more appropriate to describe the task.

The heuristics shown on the previous two pages should be borne in mind whilst preparing the GTMs.

- Generify (scope system at task level)

This involves the following steps, which are described in more detail afterwards.

Prepare GTM(y)

obtain SoR; note temporal and conditional aspects

summarise task in device independent terms

summarise subtasks in device independent terms

prepare documents

Prepare GTM(x)

obtain GTM(ext)s

compare to GTM(y)

identify elements of (ext) relevant to (y)

identify compatible GTM(ext) components

synthesise parts into GTM(x)

Preparing GTM(y)

GTM(y) is based on the Statement of Requirements (SoR). The SoR should be reviewed and the main tasks identified. Any requirements concerning the ordering of the tasks or conditions under which they should be performed should be noted, and a diagram similar to those generated for the GTM(ext)s should be produced, summarising the requirements in device independent terms.

If the GTM(y) is unexpectedly simple, this should not necessarily be regarded as indicating a error of production, but may indicate that subsequent enhancement of aspects of the requirements specification may be required.

A supporting table should be prepared for the GTM(y), which should follow the structure shown below.

| Name |

Description |

Observation |

Design

Implication |

Speculation |

| Which cell is referred to |

Further description as necessary |

Any notes |

Any implications , based on ESA work |

Any design speculations occurring at this stage |

Preparing GTM(x)

GTM(x) is a device independent model of the aspects of the existing systems that might be suitable for incorporation in the target system. The model is based on the GTM(ext) products that were prepared for each system studied during the extant systems analysis. The information in the supporting tables for the Task Descriptions (TD(ext)) may be useful when deciding which parts of the GTM(ext)s to include, particularly any comments in the implications or observations columns. The comments from the TD tables can be copied into the supporting tables for the GTM(x), but care should be taken to updated the names of the nodes where necessary. If appropriate, the GTM table can be cross-referenced to the original task description to provide additional information. Information about the problems experienced by users gathered during the interviews should be reviewed in case it contains relevant information not in the TD tables.

A supporting table should be prepared for the GTM(x), which should follow the same structure as the GTM(y) table.

Once the GTM(x) has been produced, it can be compared to the GTM(y). If the two models look very different, it may indicate that the new system will seem unfamiliar to the users, who will either require additional training or extra support from the design of the interface, perhaps either through descriptions printed beside buttons, on-line help, or maybe a wizard or agent. If the GTM(x) is not very extensive, it probably indicates that the systems studied during analysis did not provide many promising ideas, and it may be an idea to revisit the analysis stage unless GTM(y) is particularly complete and the system is well understood.

- Verify models

Partial verification of the models has already been performed, when the users were interviewed and shown the partly completed task descriptions. The completed TD(ext)s and GTMs may be checked with user representatives to provide additional confidence concerning their completeness and accuracy before further work is based upon them.

| GTM Rating table

Please rate the above procedures according to the extent they fit the descriptions in the left hand column

|

| |

Agree strongly |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Disagree Strongly |

Coherent

(i.e. understandable) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

| Complete

(i.e. there was nothing missing) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

| Concerned what was desired

(i.e. did the procedures allow you to do what you were supposed to?) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

|

Time taken:

|

Diagrams |

Tables |

Revision |

Other (specify) |

|

Further

Comments:

|

* Please describe what the problem was |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Phase 2

Design Synthesis

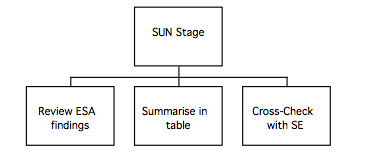

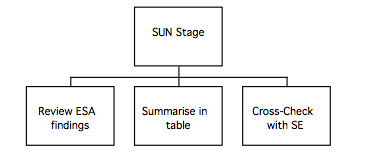

MUSE(SE) Phase 2 Procedures: SUN stage

The purpose of the SUN is to summarise the ESA findings so that they can easily be referred to during the remainder of the design process; in effect, the SUN presents a human factors perspective on the Statement of Requirements. The process of producing the SUN mostly involves summarising the findings from previous stages, and is quite straightforward as the following diagram shows.

- Document user problems

The information gathered during ESA analysis, particularly that marked for inclusion in the Statement of User Needs, is now collated to form SUN(y). It is important that the SUN lists both good and bad aspects of the systems studied, so that the good features are preserved in the target system and the bad aspects of the existing system do not reappear. Insights gained into problems or benefits caused by the relationships between aspects of the worksystem, such as mismatches between the users mental model of the task and the way it is represented by the system, or the association between actions and the objects that perform or suffer them, should have been uncovered both during assessment with the styleguide, guidelines and related heuristics and during the observational studies; these are recorded in the various sections of the SUN. The information collected concerning the characteristics of the target user groups is also incorporated into SUN(y), as are the ‘usability requirements’ (PLUME categories and the styleguide chosen) that define the acceptable properties for the target system.

The SUN is divided into six sections, which are listed on the next page; each section contains guidance about which of the activities carries out during examination of the existing systems is most likely to provide the relevant information.

Each section of the finished SUN should contain a pair of tables. The tables describe the good and bad features of the existing system and how these are to be reflected by the target system. The tables are shown after the sections on the next page.

The SUN is divided into the sections shown in the following table:

| Statement of User Needs Sections |

User and Device Actions

(from checklist sections 1-8, observational studies, interviews, and the task models) |

User mental processes and mental model

(from interviews, card sorting, verbal protocol, and task models) |

Task (Domain) Objects

– Goals (from interviews and card sorting)

– Domain objects (from observation, interviews and card sorting)

– Task quality (from usability tests) (Performance from PLUME – record target level from Usability requirements) |

User and device costs

(from observations, task execution, usability tests, informal tests, as well as sections 1, 3, 5 , 6 and 10 of the checklist)

– Learnability (also record target level from Usability requirements)

– User satisfaction (also record target level from Usability requirements)

– Memorability, Learnability (also record target level from Usability requirements)

– Errors (and time on task);(also record target level from Usability requirements) |

Physical aspects; device construction, appearance and layout.

(from physical guidelines, and sections 1, 5, and 10 of checklist) |

Miscellaneous

(from sections 3-10 of the checklist). |

Each section of the SUN should follow the format shown below:

| Problem |

Caused by |

Consequences |

Addressed by |

| What problem the users suffer

(complete now) |

Feature of the existing system that causes the problem

(complete now) |

Impact on the target system; what will have to be done to avoid recurrence

(complete either now or later) |

How the target system has addressed the problem

(complete later) |

| Feature |

Caused by |

Consequences |

Addressed by |

| Desirable aspect of existing system that the target system should keep

(complete now) |

Feature of the existing system that causes the feature

(complete now) |

Potential impact on the target system; what will have to be done to preserve feature

(complete either now or later) |

How the target system has addressed the problem

(complete later) |

OMT Cross-Checking Point:

Refer to the object model, event flow (or object message) diagram and event (or message) trace generated as part of the OMT process, and carry out the following checks. (It may be more convenient to perform this check at the same time as the DoDD(y) check in the next stage).

Review the SUN to ensure that users did not report difficulties communicating with the system (i.e. with the language or the semantics of the old user interface). Consider whether these are likely to recur in the new system, by looking at the event flow and event trace and assess whether good points of the old system have been reused as appropriate.

Check that any objects from the domain and their attributes mentioned in the SUN are treated appropriately in the Object model.

Ensure that associations between actions and objects noted in the SUN are treated appropriately in the Object model, by considering whether each object has appropriate attributes and methods. (Check that there is a ‘User Interface’ class, as well as the interface-related classes in the DoDD(y); it won’t be very detailed yet, but it will be required later on).

| SUN Rating table

Please rate the above procedures according to the extent they fit the descriptions in the left hand column

|

| |

Agree strongly |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Disagree Strongly |

Coherent

(i.e. understandable) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

| Complete

(i.e. there was nothing missing) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

| Concerned what was desired

(i.e. did the procedures allow you to do what you were supposed to?) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

|

Time taken:

|

Diagrams |

Tables |

Revision |

Other (specify) |

|

Further

Comments:

|

* Please describe what the problem was |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

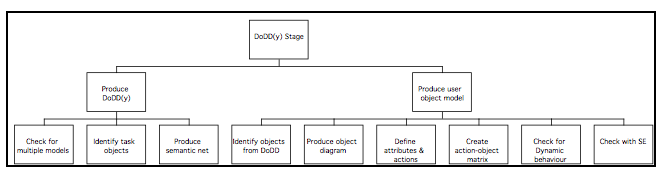

MUSE(SE) Phase 2 Procedures: DoDD(y) stage

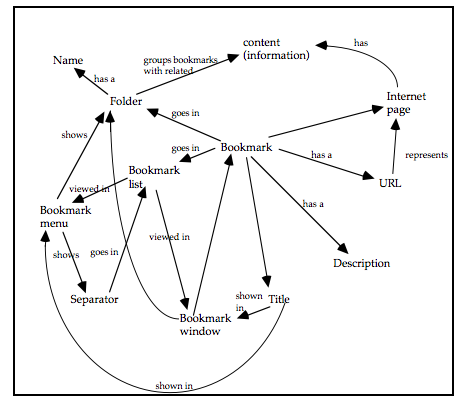

The user’s view of the task domain is modelled to provide insight into their mental model of the task and allow the user interface to be specified in such a way that it will be easily understood by the user and be easy to learn and use. Two models of the task domain are produced, a semantic net called the DoDD(y), and the user object model. The user object model resembles a software engineering model more closely than the DoDD(y), and in fact uses software engineering notations. The main difference between the two models is that the user object model describes the objects together with their attributes and actions performed and suffered (i.e. the operational relationships between objects), whereas the semantic net describes the objects and the semantics of the relationships between them.

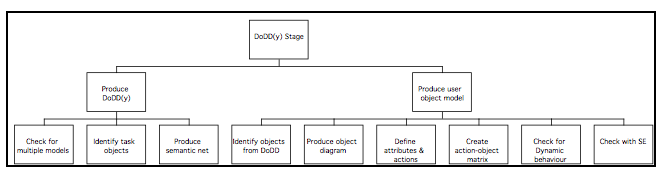

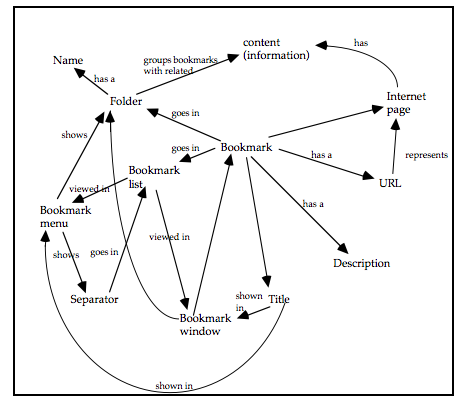

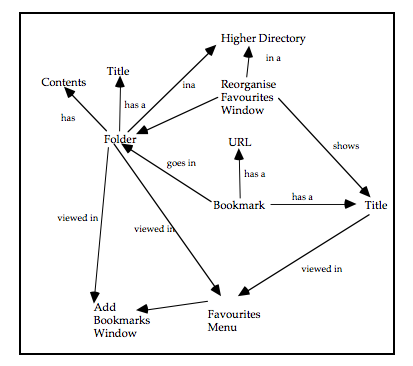

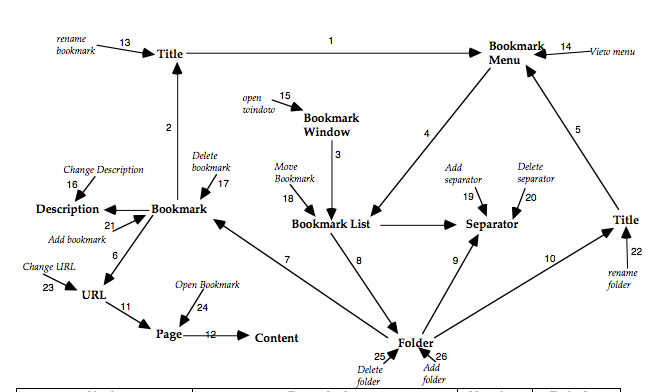

The following diagram summarises the production of the DoDD(y) and user object models:

Production of the DoDD(y) user object model and semantic net is based on the information derived during ESA analysis. The object of constructing the DoDD(y) is to represent the aspects of the task domain that are important from the user’s point of view. The DoDD(y) uses a fairly informal notation, and its content is determined more by what is useful in a particular instance than by a set recipe. The DoDD(y) is used as an informal ‘mind-map’ to help the designer understand and reason about the problem.

The DoDD(y) should not merely reproduce material in the software engineering specifications (e.g. the object model), because whereas software engineering specifications concern how the system will actually work, the DoDD(y) should reflect how the user thinks it works. The DoDD(y) is used to help the designer reason about the design at later stages, and the process of creating the DoDD(y) can suggest questions to ask the users that might not otherwise occur. For example, when constructing a DoDD(y) to describe the domain of an email client, the password would probably appear as an entity with an association concerning ‘security’. Questioning users further might reveal that they consider that ‘security’ has to do with all their mailboxes rather than just the new messages on the server, which might prompt consideration of whether the design should reflect this in its treatment of the password.

The following information may be included in the DoDD(y):

- the main (high-level) task behaviours derived from observation and interviews

- mental representations derived from interviews, verbal protocols, and card sorting,

- information on domain objects and attributes derived from observations, interviews and card sorting.

In addition, the following relationships uncovered during assessment using guidelines should be recorded: the associations between actions and the main task objects; the task goals, and work domain objects; the relationships between abstract IWS structures and task goals, work domain objects, and physical IWS structures, derived from the relevant parts of the checklist and the interviews. The relationship between physical IWS structures and domain objects and performance may also be of relevance to the DoDD(y).

Production of the DoDD(y) should be largely a matter of consolidating the semantic nets produced during the interviews. The DoDD(y) should be device independent, in that it should refer to the objects manipulated by users to perform the work rather than the specifics of how the task is done using any of the devices studied. The level of description should be sufficient to explain the tasks from the user’s point of view, but need not go into technical detail.

To produce the DoDD(y) semantic net, the following procedures should be employed:

- Check for multiple models

The first activity in defining the user object model is to assess whether multiple models are required, by considering the user groups identified at the start of the extant systems analysis stage. In a large system there may be two or more user classes for whom the ‘objects in the system’ are almost completely different. Although it is sometimes necessary to define two or more user object models to form the basis of different subsystems, it is not always necessary to have a separate user object model for every user class. An object model should be broad enough to cover the requirements of several user classes concerned with the same objects.

- Obtain the Statement of Requirements, the GTMs, and the products generated during extant systems analysis (particularly the semantic nets produced when the users were interviewed).

- Review the documents listed above to extract a list of domain objects, concepts, events, and processes.

- Arrange the domain objects on the page and insert arrows to show their relationships with one another. Number the arrows, and describe each relationship in a table like the one below.

| Node |

Description |

Number |

Relation |

| The name of the object as shown in the diagram |

Description of the object sufficient to identify it in the task |

Number on the arrow |

The relationship between the object and the one pointed to. |

- Add the concepts, events, and processes, and draw lines connecting them to their associated object, documenting them in the table as shown above; it doesn’t matter if they look the same as the objects, as long as the diagram makes sense to the users and is understood by the interface designer.

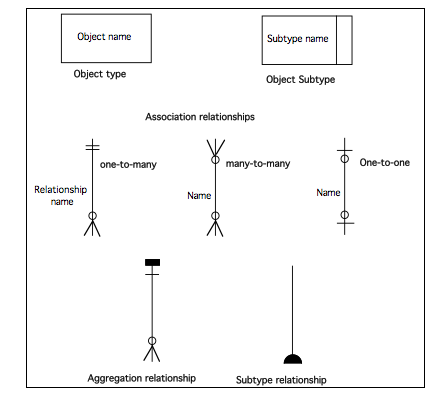

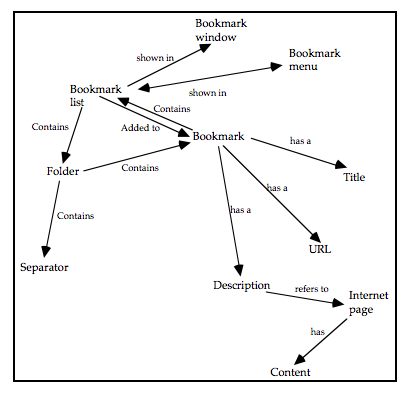

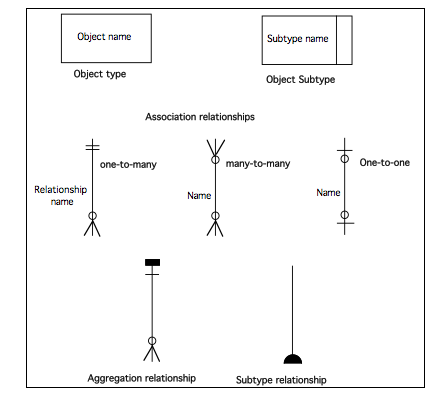

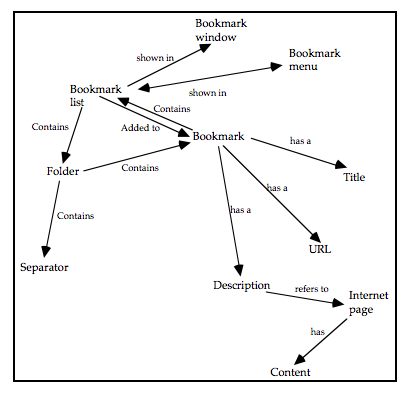

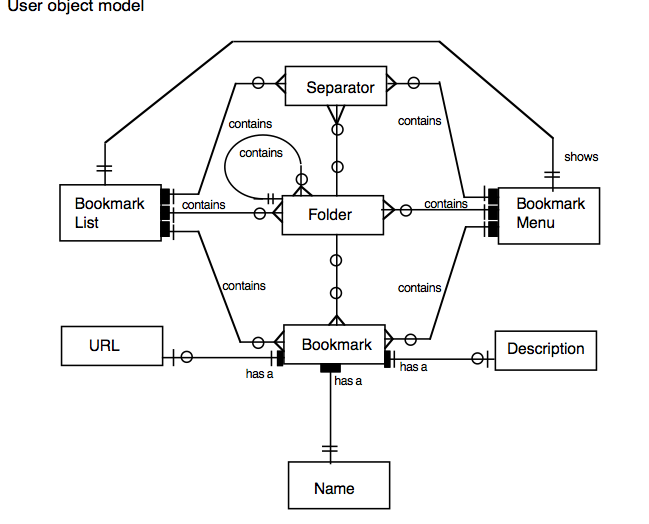

Once the DoDD(y) is complete, prepare the user object model [2]. The notation for the user object model is based on that of OMT (Rumbaugh, 1991), although any notation that includes object types or classes, subtypes, association relationships and aggregation or composition relationships could be used. Note that attributes and actions are part of the user object model but are not usually shown on the diagram.

The notational constructs used in the user object model are shown in the following diagram.

[1]The user object model is taken from Redmond-Pyle, D., and Moore, A., (1995) ‘

Graphical User Interface Design and Evalution (GUIDE): A practical Process’, Prentice Hall, London, and the user object model procedures reproduced here are based on those by Redmond-Pyle

To produce the user object model, the following procedures should be employed:

Refer to the objects in the DoDD(y). For each object consider the following questions:

- Does the user need to see and interact with the object to perform their tasks?

- Does the object group together related information in a way that helps the user to perform a specific task?

- Does the object exist in the business world, and will it continue to exist with the new system?

- Is the object a useful system object, which the user needs to see and interact with (e.g. printer, fax machine) or should it be invisible to the user (e.g. modem)?

- Is the object just an artifact of the old system, which will be made redundant by the new system? (If so it is probably not required in the user object model, unless it is still a helpful illusion for the end-user.)

If the object is merely a source or recipient of information in the task and the user does not need to see or manipulate the object, then the object may not be required as a user object. An alternative is to interact with the object via some standard communication mechanism such as an electronic mail mailbox.

- Create user object model diagram

Take care to give each object the name that the user wants to call it in the interface. Analyze the relationships between the objects. For each user object, consider which other types of user object it is directly related to. For example, a Person object may ‘own’ a Car object. Define the cardinality of the relationships (one-to-many, manyto-many, etc). For example, one Person may own many Cars, but each Car is owned by one Person. Use a user object model diagram to show all the user objects and the relationships between them. There will often be ‘contains’ relationships, showing container objects (such as lists) related to the objects they contain. Many-to-many relationships are common and oneto-one relationships are quite acceptable. Note the number of occurrences of each user object (e.g. there is only one System object, but there are 1000 Customers and 9000 Orders.)

- Define user object attributes

Define the attributes of each object, i.e. the pieces of information the user knows about the object. For example, a Person object might have a Name, an Address, an Employer, a Date of Birth, a Photograph, a Signature and a List of Leisure Activities. Note that Photograph and (handwritten) Signature are perfectly sensible attributes, even though they are not conventional database fields.

The criteria to use in deciding whether a piece of information should be an attribute of a particular user object are whether it is useful to support a task, and whether it seems sensible to the user. (Avoidance of redundancy, extent of normalization, etc., are not appropriate quality criteria for user object models.)

- Define user object actions

Identify the actions the user will need to perform on (or using) the object, such as Print, Calculate, Authorize, Send to, Allocate to, Add.

User object actions are identified from user tasks, and from discussions with users. Most user objects will have actions to Create or Delete. Establishing (or removing) a rellationship between one user object and another is another common action. Some actions relate to the whole user object, while other actions may only relate to part of the object.

Additional user object actions may be identified and added later, while expressing ask scenarios as sequences of user object actions, and during prototyping. Define each action in terms of the following:

- A brief narrative description

- Any input

- The required effect on object attributes and relationships

- Any output

User object actions describe the ‘behaviour’ of objects in the system. They are the main means of specifying required system functionality. The actions on a user object are considered to be part of the object.

- Create action–object matrix

Create a matrix to show how update actions affect objects.

The action–object matrix provides a useful way of checking the scope and complexity of actions. Most user object actions only affect one user object. However, where an action does affect more than one object, this is significant for GUI design. When the user performs the action on one object, will they expect the effects on other objects to occur?

Construction and review of the matrix often leads to additional actions being identified, to actions being redefined, or to additional effects being noted.

- Check for dynamic behaviour

For each object in turn, consider whether there is significant dynamic behaviour. For the actions of an object, consider the following:

- Can the actions be invalid, depending on the prior state of the object? (Make a note of this for later. This will help during the detailed design of the user interface.

- Are there any constraints on the sequence in which the actions can occur?

(Check that the ordering constraints are represented in the GTM(y)).

OMT Cross-Checking Point:

Refer to the object model, scenarios and use cases generated as part of the OMT process, and carry out the following checks.

Review the DoDD to establish the conceptual entities and operations that form part of the user’s model. Check the OMT object model to ensure that the entities are present as objects, and that the operations are likely to be supported by the methods.

Check the object model against the DoDD(y) to ensure that the objects and their associations agree with the users’ mental representations of the task domain as much as possible.

Check the objects in the DoDD(y) are present in the object model, and in the scenarios and use cases used by OMT. Objects that perform or suffer actions in the DoDD(y) should have dynamic models, as they change state from the user’s point of view. Physical attributes of objects may appear in the DFD (functional model) as data flows, and should appear in the object model as attributes of their objects. Abstract attributes should appear in the object model, and as control flows in the DFD, and may appear in the state diagram as events, attributes or conditions on transitions or within states. (Attribute values derived from user inputs may appear in the event (or message) trace as event parameters, and those actions associated with objects that initiate events may also need to appear in the event trace). Actions associated with objects in the DoDD(y) should be present in the object model as operations.

The actions from the DoDD(y) should be correctly associated with the objects in the object model; in the state diagrams the correct objects should be undergoing transformations or participating in event passing. The methods that initiate events in the DoDD(y) should feature in the scenarios and use cases, and the data transformed by methods in the DFD should agree with the DoDD(y). Similarly, state transitions in the DoDD(y) should be represented in the state diagram.

| DoDD(y) Rating table

Please rate the above procedures according to the extent they fit the descriptions in the left hand column

|

| |

Agree strongly |

Agree |

Neutral |

Disagree |

Disagree Strongly |

Coherent

(i.e. understandable) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

| Complete

(i.e. there was nothing missing) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

| Concerned what was desired

(i.e. did the procedures allow you to do what you were supposed to?) |

|

|

|

* |

* |

|

Time taken:

|

Diagrams |

Tables |

Revision |

Other (specify) |

|

Further

Comments:

|

* Please describe what the problem was |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

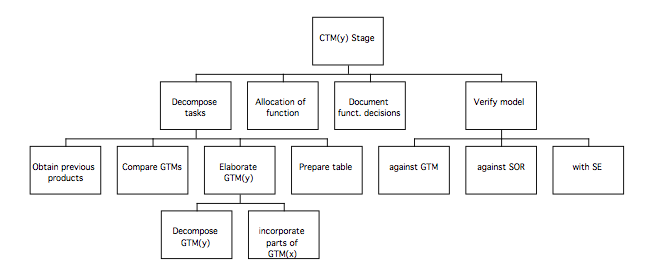

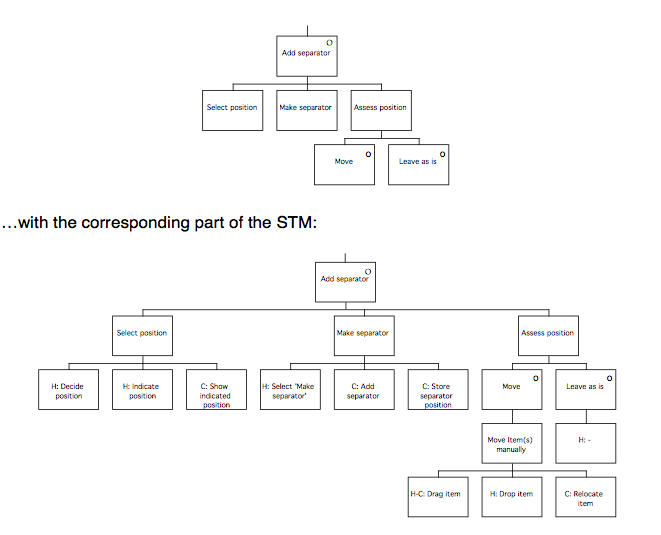

Procedures for phase 2 of MUSE(SE): CTM(y) stage

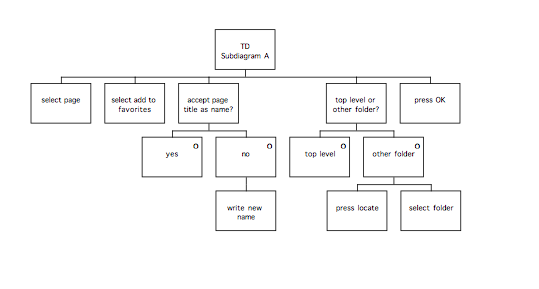

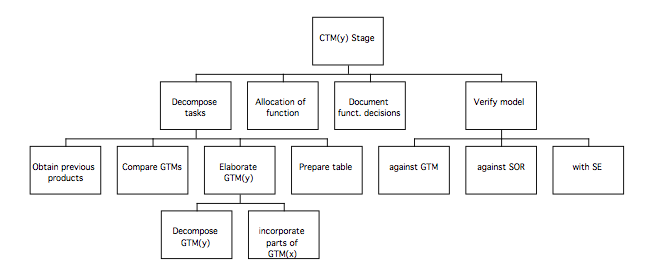

The high level procedures for the CTM(y) stage of MUSE(SE) may be summarised as shown in the following diagram:

Most of the information required to specify the CTM(y) should be present in the SUN and DoDD(y), particularly where arbitration between alternative design options contained in the GTMs is required.

- Decompose task

Decomposition of the task involves increasing the level of detail so that the designed task satisfies the statement of requirements; this is achieved by selecting components of the GTM(x) and GTM(y) and describing them in more detail to arrive at a conceptual design for the system.

Where a detailed statement of requirements exists, CTM(y) may be very similar to GTM(y). However, the statement of requirements may sometimes be vague, incomplete or even almost non-existent, which results in an impoverished GTM(y). In these circumstances, the CTM(y) should be based more on GTM(x) and the requirements must be updated to reflect this. Even where the statement of requirements provides a detailed functional specification of the target system, it may not contain sufficient information to enable the structure of the task and ordering of subtasks to be specified. In this case, the CTM would reflect the content of GTM(y), but those aspects of the structure of GTM(x) found to be unproblematic during extant systems analysis should be reused; the remainder of the structure should be revised in such a way as to avoid any problems noted.

1a Synthesis: Obtain SoR, DoDD(y), and SUN

Compare GTM(x) and GTM(y)

Extend GTM(y)

Incorporate parts of GTM(x)

The SUN(y) should inform arbitration between the GTM(x) and the GTM(y) by virtue of information concerning evaluation or commentary on the IWS behaviours and the decomposition gathered in the observational studies conducted during the ESA stage, as well as the heuristic evaluation findings. The heuristics that are presented after the procedures for this stage should be used to help selection from the GTMs and elaboration of the CTM.

The objective is to elaborate the GTM(y), describing the subtasks in greater detail to arrive at a more detailed conceptual design for the system.

The correct level of detail in the CTM is where the tasks are described in sufficient detail that all of the steps are included. The CTM should not describe which tasks are done by the user and which are done by the computer or the turn-taking in the interaction; this level of detail will be dealt with later.

1b Record in table:

Design rationale

Design decisions

The CTM(y) supporting table should record the rationale for decisions made concerning the structure of the task. Any porting from GTM(x) or TDs should be noted in the table. If any design decisions made involve changing the structure inherited from GTM(y), the statement of requirements may require modification; this should be noted in the ‘Design Comments’ column and the person responsible for the requirements should be consulted as soon as possible.

The table should take the following form:

| Name |

Description |

Design Comments |

| Name of the node |

Description of the node |

Any commentary required, such as the rationale |

2 Perform allocation of function on basis of ESA and SUN(y)

Refer back to the observations and design implications columns of the GTM and TD tables, to identify information gathered in the ESA stage relevant to allocation of function decisions.