Conceptions of the Discipline of HCI: Craft; Applied Science, and Engineering

John Long and John Dowell

Ergonomics Unit, University College London,

26 Bedford Way, London. WC1H 0AP.

Pre-print: In: Sutcliffe, A. andMacaulay, L., (eds.) People and Computers V: Proceedings of the Fifth Conference of the British Computer Society.(pp. pp. 9-32). Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK. http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/15292/

The theme of HCI ’89 is ‘the theory and practice of HCI’. In providing a general introduction to the Conference, this paper develops the theme within a characterisation of alternative conceptions of the discipline of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI). First, consideration of disciplines in general suggests their complete definition can be summarised as: ‘knowledge, practices and a general problem having a particular scope, where knowledge supports practices seeking solutions to the general problem’. Second, the scope of the general problem of HCI is defined by reference to humans, computers, and the work they perform. Third, by intersecting these two definitions, a framework is proposed within which different conceptions of the HCI discipline may be established, ordered, and related. The framework expresses the essential characteristics of the HCI discipline, and can be summarised as: ‘the use of HCI knowledge to support practices seeking solutions to the general problem of HCI’. Fourth, three alternative conceptions of the discipline of HCI are identified. They are HCI as a craft discipline, as an applied scientific discipline, and as an engineering discipline. Each conception is considered in terms of its view of the general problem, the practices seeking solutions to the problem, and the knowledge supporting those practices; examples are provided. Finally, the alternative conceptions are reviewed, and the effectiveness of the discipline which each offers is comparatively assessed. The relationships between the conceptions in establishing a more effective discipline are indicated.

Published in: People and Computers V. Sutcliffe A. and Macaulay L. (ed.s). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Proceedings of the Fifth Conference of the BCS HCI SIG, Nottingham 5-8 September 1989.

Contents

1. Introduction

1.1. Alternative Interpretations of the Theme

1.2. Alternative Conceptions of HCI: the Requirement for a Framework

1.3. Aims

2. A Framework for Conceptions of the HCI Discipline

2.1. On the Nature of Disciplines

2.2. Of Humans Interacting with Computers

2.3. The Framework for Conceptions of the HCI Discipline

3. Three Conceptions of the Discipline of HCI

3.1. Conception of HCI as a Craft Discipline

3.2. Conception of HCI as an Applied Science Discipline

3.3. Conception of HCI as an Engineering Discipline

4. Summary and Conclusions

1. Introduction

HCI ’89 is the fifth conference in the ‘People and Computers’ series organised by the British Computer Society’s HCI Specialist Group. The main theme of HCI ’89 is ‘the theory and practice of HCI’. The significance of the theme derives from the questions it prompts and from the Conference aims arising from it. For example, what is HCI? What is HCI practice? What theory supports HCI practice? How well does HCI theory support HCI practice? Addressing such questions develops the Conference theme and so advances the Conference goals.

1.1. Alternative Interpretations of the Theme

Any attempt to address these questions, however, admits no singular answer. For example, some would claim HCI as a science, others as engineering. Some would claim HCI practice as ‘trial and error’, others as ‘specify and implement’. Some would claim HCI theory as explanatory laws, others as design principles. Some would claim HCI theory as directly supporting HCI practice, others as indirectly providing support. Some would claim HCI theory as effectively supporting HCI practice, whilst others may claim such support as non-existent. Clearly then, there will be many possible interpretations of the theme ‘the theory and practice of HCI’.

Answers to some of the questions prompted by the theme will be related. Different answers to the same question may be mutually exclusive; for example, types of practice as ‘trial and error’ or ‘specify and implement’ will likely be mutually exclusive. Answers to different questions may also be mutually exclusive; for example, HCI as engineering would likely exclude HCI theory as explanatory laws, and HCI practice as ‘trial and error’. And moreover, answers to some questions may constrain the answers to other questions; for example, types of HCI theory, perhaps design principles, may constrain the type of practice, perhaps as ‘specify and implement’.

1.2. Alternative Conceptions of HCI: the Requirement for a Framework

It follows that we must admit the possibility of alternative, and equally legitimate, conceptions of the HCI discipline – and therein, of its theory and practice. A conception of the HCI discipline offers a unitary view; its value lies in the coherence and completeness with which it enables understanding of the discipline, how the discipline operates, and its effectiveness. So for example, a conception of HCI might be either of a scientific or of an engineering discipline; its view of the theory and practice of the discipline would be different in the two cases. Its view of how the discipline might operate, and its expectations for the effectiveness of the discipline, would also be different in the two cases. This paper identifies alternative conceptions of HCI, and attempts a comparative assessment of the (potential) effectiveness of the discipline which each views. The requirement for identifying the different conceptions is both prompted and required by the development of the Conference theme.

To advance alternative conceptions of HCI, however, it is necessary first to formulate some form of analytic structure to ensure that conceptions supposed as alternatives are both complete and of the same subject, rather than being conceptions of complementary, or simply different, subjects. A suitable structure for this purpose would be a framework identifying the essential characteristics of the HCI discipline. By such a framework, instances of conceptions of the HCI discipline – claimed to be substantively different, but equivalent – might be established, ordered, and related. And hence, so might their views of its theories and practices.

The aims of this paper follow from the need to identify alternative conceptions of HCI as a discipline. The aims are described in the next section.

1.3. Aims

To address and develop the Conference theme of ‘the theory and practice of HCI’ – and so to advance the goals of HCI ’89 – the aims of this paper are as follows:

(i) to propose a framework for conceptions of the HCI discipline

(ii) to identify and exemplify alternative conceptions of the HCI discipline in terms of the framework

(iii) to evaluate the effectiveness of the discipline as viewed by each of the conceptions, and to indicate the possible relationships between the conceptions in establishing a more effective discipline.

2. A Framework for Conceptions of the HCI Discipline

Two prerequisites of a framework for conceptions of the HCI discipline are assumed. The first is a definition of disciplines appropriate for the expression of HCI. The second is a definition of the province of concern of the HCI discipline which, whilst broad enough to include all disparate aspects, enables the discipline’s boundaries to be identified. Each of these prerequisites will be addressed in turn (Sections 2.1. and 2.2.). From them is derived a framework for conceptions of the HCI discipline (Section 2.3.). Source material for the framework is to be found in (Dowell & Long [1988]; Dowell & Long [manuscript submitted for publication]; and Long [1989]).

2.1. On the Nature of Disciplines

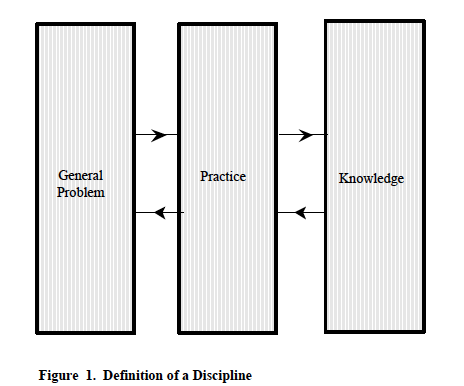

Most definitions assume three primary characteristics of disciplines: knowledge; practice; and a general problem.

All definitions of disciplines make reference to discipline knowledge as the product of research or more generally of a field of study. Knowledge can be public (ultimately formal) or private (ultimately experiential). It may assume a number of forms; for example, it may be tacit, formal, experiential, codified – as in theories, laws and principles etc. It may also be maintained in a number of ways; for example, it may be expressed in journals, or learning systems, or it may only be embodied in procedures and tools. All disciplines would appear to have knowledge as a component (for example, scientific discipline knowledge, engineering discipline knowledge, medical discipline knowledge, etc). Knowledge, therefore, is a necessary characteristic of a discipline.

Consideration of different disciplines suggests that practice is also a necessary characteristic of a discipline. Further, a discipline’s knowledge is used by its practices to solve a general (discipline) problem. For example, the discipline of science includes the scientific practice addressing the general (scientific) problem of explanation and prediction. The discipline of engineering includes the engineering practice addressing the general (engineering) problem of design. The discipline of medicine includes the medical practice addressing the general (medical) problem of supporting health. Practice, therefore, and the general (discipline) problem which it uses knowledge to solve, are also necessary characteristics of a discipline.

Clearly, disciplines are here being distinguished by the general (discipline) problem they address. The scientific discipline addresses the general (scientific) problem of explanation and prediction, the engineering discipline addresses the general (engineering) problem of design, and so on. Yet consideration also suggests those general (discipline) problems each have the necessary property of a scope. Decomposition of a general (discipline) problem with regard to its scope exposes (subsumed) general problems of particular scopes. ((Notwithstanding the so-called ‘hierarchy theory ‘ which assumes a phenomenon to occur at a particular level of complexity and to subsume others at a lower level (eg, Pattee, 1973).)) This decomposition allows the further division of disciplines into sub-disciplines.

For example, the scientific discipline includes the disciplines of physics, biology, psychology, etc., each distinguished by the particular scope of the general problem it addresses. The discipline of psychology addresses a general (scientific) problem whose particular scope is the mental and physical behaviours of humans and animals. It attempts to explain and predict those behaviours. It is distinguished from the discipline of biology which addresses a general problem whose particular scope includes anatomy, physiology, etc. Similarly, the discipline of engineering includes the disciplines of civil, mechanical, electrical engineering, etc. Electrical engineering is distinguished by the particular scope of the general (engineering) problem it addresses, i.e., the scope of electrical artefacts. And similarly, the discipline of medicine includes the disciplines of dermatology, neurology etc., each distinguished by the particular scope of the general problem it addresses.

Two basic properties of disciplines are therefore concluded. One is the property of the scope of a general discipline problem. The other is the possibility of division of a discipline into sub-disciplines by decomposition of its general discipline problem.

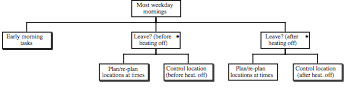

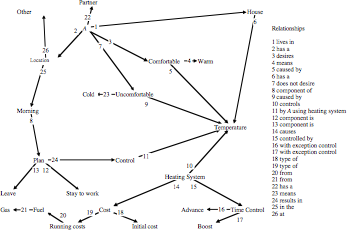

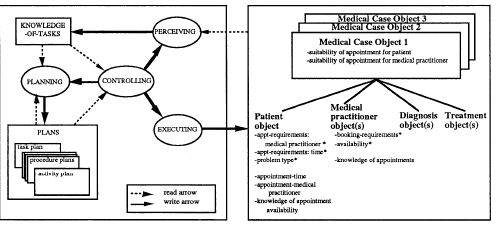

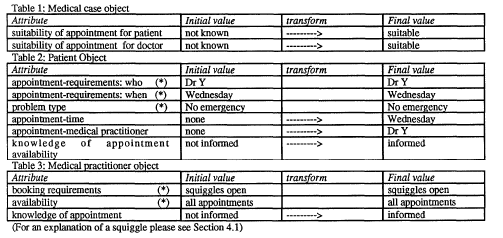

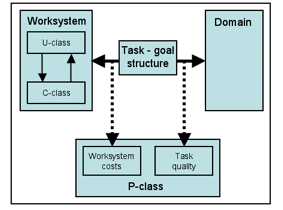

Taken together, the three necessary characteristics of a discipline (and the two basic properties additionally concluded), suggest the definition of a discipline as: ‘the use of knowledge to support practices seeking solutions to a general problem having a particular scope’. It is represented schematically in Figure 1. This definition will be used subsequently to express HCI.

2.2. Of Humans Interacting with Computers

The second prerequisite of a framework for conceptions of the HCI discipline is a definition of the scope of the general problem addressed by the discipline. In delimiting the province of concern of the HCI discipline, such a definition might assure the completeness of any one conception (see Section 1.2.).

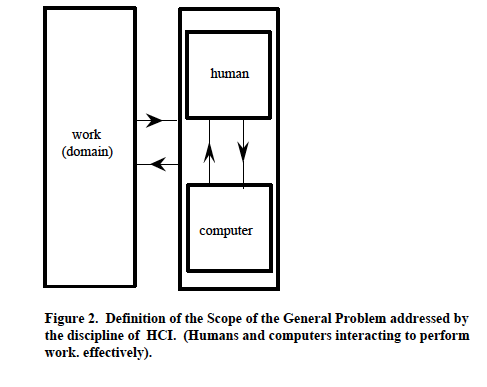

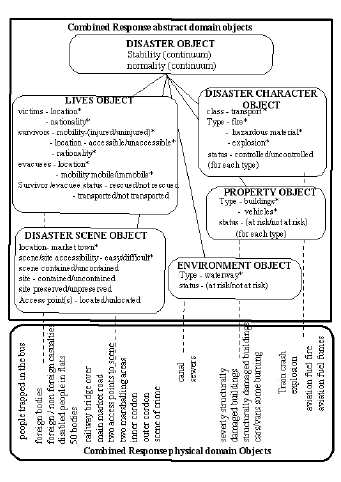

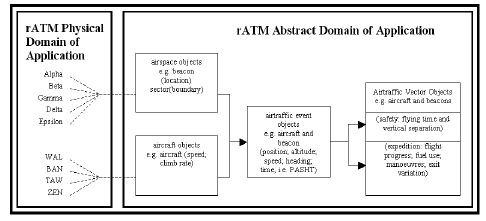

HCI concerns humans and computers interacting to perform work. It implicates: humans, both individually and in organisations; computers, both as programmable machines and functionally embedded devices within machines (stand alone or networked); and work performed by humans and computers within organisational contexts. It implicates both behaviours and structures of humans and computers. It implicates the interactions between humans and computers in performing both physical work (ie, transforming energy) and abstract work (ie, transforming information). Further, since both organisations and individuals have requirements for the effectiveness with which work is performed, also implicated is the optimisation of all aspects of the interactions supporting effectiveness.

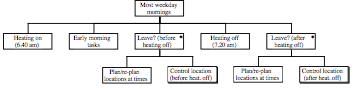

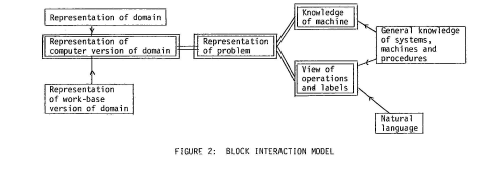

Taken together, these implications suggest a definition of the scope of the general (discipline) problem of HCI. It is expressed, in summary, as ‘humans and computers interacting to perform work effectively’; it is represented schematically in Figure 2. This definition, in conjunction with the general definition of disciplines, will now enable expression of a framework for conceptions of the HCI discipline.

2.3. The Framework for Conceptions of the HCI Discipline

The possibility of alternative, and equally legitimate, conceptions of the discipline of HCI was earlier postulated. This section proposes a framework within which different conceptions may be established, ordered, and related.

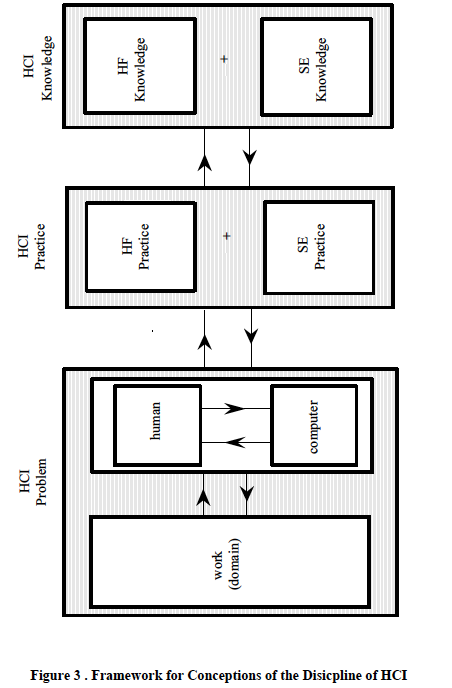

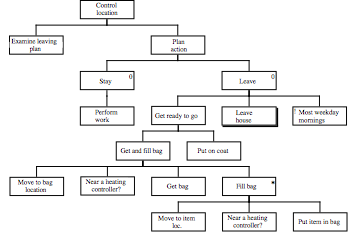

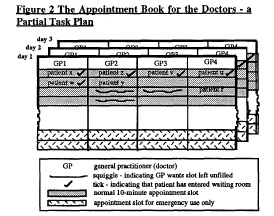

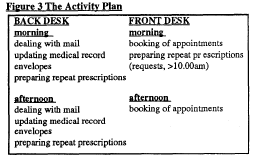

Given the definition of its scope (above), and the preceding definition of disciplines, the general problem addressed by the discipline of HCI is asserted as: ‘the design of humans and computers interacting to perform work effectively’. It is a general (discipline) problem of design : its ultimate product is designs. The practices of the HCI discipline seek solutions to this general problem, for example: in the construction of computer hardware and software; in the selection and training of humans to use computers; in aspects of the management of work, etc. HCI discipline knowledge supports the practices that provide such solutions.

The general problem of HCI can be decomposed (with regard to its scope) into two general problems, each having a particular scope. Whilst subsumed within the general problem of HCI, these two general problems are expressed as: ‘the design of humans interacting with computers’; and ‘the design of computers interacting with humans’. Each problem can be associated with a different sub-discipline of HCI. Human Factors (HF), or Ergonomics, addresses the problem of designing the human as they interact with a computer. Software Engineering (SE) addresses the problem of designing the computer as it interacts with a human. With different – though complementary – aims, both sub-disciplines address the problem of designing humans and computers which interact to perform work effectively. However, the HF discipline concerns the physical and mental aspects of the human and is supported by HF discipline knowledge. The SE discipline concerns the physical and software aspects of the computer and is supported by SE discipline knowledge.

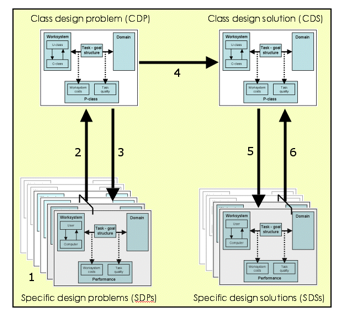

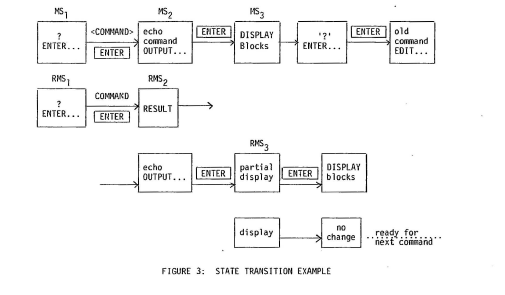

Hence, we may express a framework for conceptions of the discipline of HCI as:

‘the use of HCI knowledge to support practices seeking solutions to the general problem of HCI of designing humans and computers interacting to perform work effectively. HCI knowledge is constituted of HF knowledge and SE knowledge, respectively supporting HF practices and SE practices. Those practices respectively address the HF general problem of the design of humans interacting with computers, and the SE general problem of the design of computers interacting with humans’. The framework is represented schematically in Figure 3.

Importantly, the framework supposes the nature of effectiveness of the HCI discipline itself. There are two apparent components of this effectiveness. The first is the success with which its practices solve the general problem of designing humans and computers interacting to perform work effectively. It may be understood to be synonymous with ‘product quality’. The second component of effectiveness of the discipline is the resource costs incurred in solving the general problem to a given degree of success – costs incurred by both the acquisition and application of knowledge. It may be understood to be synonymous with ‘production costs’.

The framework will be used in Section 3 to establish, order, and relate alternative conceptions of HCI. It supports comparative assessment of the effectiveness of the discipline as supposed by each conception.

3. Three Conceptions of the Discipline of HCI

A review of the literature was undertaken to identify alternative conceptions of HCI, that is, conceptions of the use of knowledge to support practices solving the general problem of the design of humans and computers interacting to perform work effectively. The review identified three such conceptions. They are HCI as a craft discipline; as an applied scientific discipline; and as an engineering discipline. Each conception will be described and exemplified in terms of the framework.

3.1. Conception of HCI as a Craft Discipline

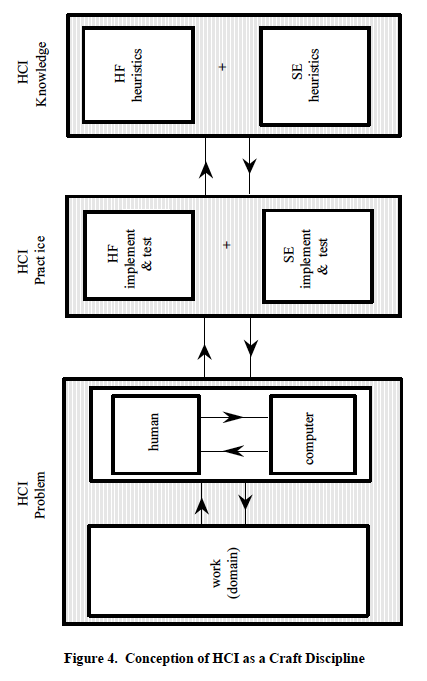

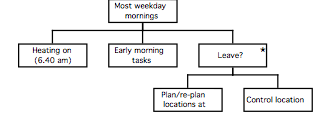

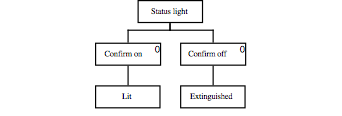

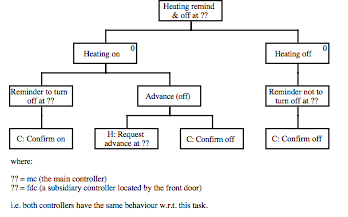

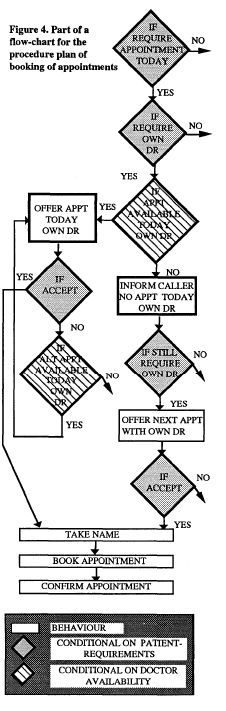

Craft disciplines solve the general problems they address by practices of implementation and evaluation. Their practices are supported by knowledge typically in the form of heuristics; heuristics are implicit (as in the procedures of good practice) and informal (as in the advice provided by one craftsperson to another). Craft knowledge is acquired by practice and example, and so is experiential; it is neither explicit nor formal. Conception of HCI as a craft discipline is represented schematically in Figure 4.

HCI as a craft discipline addresses the general problem of designing humans and computers interacting to perform work effectively. For example, Prestel uses Videotex technology to provide a public information service which also includes remote electronic shopping and banking facilities (Gilligan & Long [1984]). The practice of HCI to solve the general problem of Prestel interaction design is by implementation, evaluation and iteration (Buckley [1989]). For example, Videotex screen designers try out new solutions – for assigning colours to displays, for selecting formats to express user instructions, etc. Successful forms of interaction are integrated into accepted good practice – for example, clearly distinguishing references to domain ‘objects’ (goods on sale) from references to interface ‘objects’ (forms to order the goods) and so reducing user difficulties and errors. Screen designs successful in supporting interactions are copied by other designers. Unsuccessful interactions are excluded from subsequent implementations – for example, the repetition of large scale logos on all the screens (because the screens are written top-to-bottom and the interaction is slowed unacceptably).

HCI craft knowledge, supporting practice, is maintained by practice itself. For example, in the case of Videotex shopping, users often fail to cite on the order form the reference number of the goods they wish to purchase. A useful design heuristic is to try prompting users with the relevant information, for example, by reminding them on the screen displaying the goods that the associated reference number is required for ordering and should be noted. An alternative heuristic is to try re-labelling the reference number of the goods, for example to ‘ordering’ rather than reference number. Heuristics such as these are formulated and tried out on new implementations and are retained if associated with successful interactions. To illustrate HCI as a craft discipline more completely, there follows a detailed example taken from a case history reporting the design of a text editor (Bornat & Thimbleby [1989]).

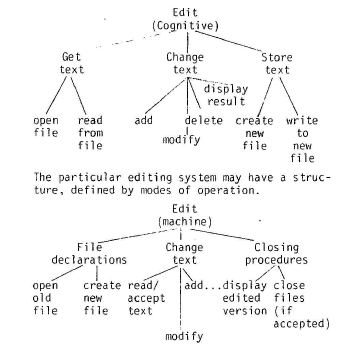

Bornat and Thimbleby are computer scientists who, in the 1970s, designed a novel text display editor called ‘Ded’. The general problem of HCI for them was to design a text editor which would enable the user to enter text, review it, add to it, to reorganise its structure and to print it. In addition, the editor was to be easy to use. They characterise their practice as ‘production’ (implementation as used here) suffused by design activity. Indeed, their view is that Ded was not designed but evolved. There was always a fully working version of the text editor to be discussed, even from the very early days.

The evolution, however, was informed by ‘user interface principles’ (which they sometimes call theories and at other times call design ideas) which they invented themselves, tried out on Ded, retained if successful and reformulated if unsuccessful. The status of the principles at the time of their use would be termed here craft discipline knowledge or heuristics. (Subsequent validation of the heuristics as other than craft knowledge would of course be possible, and so change this status.) For example, ‘to indicate to users exactly what they are doing, try providing rapid feedback for every keypress’. Most feedback was embodied in changes to the display (cursor movements, characters added or deleted, etc.) which were visible to the user. However, if the effect of a keypress was not visible, there was no effect, but a bell rang to let the user know. In this way, the craft heuristic supporting the SE craft practice – by informing the design of the computer interacting with the human – can be expressed as: ‘if key depression and no display change, then ring bell’. The heuristic also supported HF craft practice – by informing the design of the human interacting with the computer. It may be expressed as: ‘if key pressed and no display change seen, and bell heard, then understand no effect of keypress (other than bell ring)’.

Another example of a craft heuristic used by Bornat and Thimbleby (and one introduced to them by a colleague) is ‘to ensure that information in the computer is what the user thinks it is, try using only one mode’. The heuristic supported SE practice, informing the design of the computer interacting with the human – ‘if text displayed, and cursor under a character, and key depression, then insert character before cursor position’. The heuristic also supported HF practice, informing the design of the human interacting with the computer – ‘if text seen, and cursor located under a character, and key has been pressed, then only the insertion of a character before the cursor position can be seen to be effected (but nothing else)’.

In summary, the design of Ded by Bornat and Thimbleby illustrates the critical features of HCI as a craft discipline. They addressed the specific form of the general problem (general because their colleague suggested part of the solution – one ‘mode’ – and because their heuristics were made available to others practising the craft discipline). Their practices involved the iterative implementation and evaluation of the computer interacting with the human, and of the human interacting with the computer. They were supported by craft discipline heuristics – for example: ‘simple operations should be simple, and the complex possible’. Such craft knowledge was either implicit or informal; the concepts of ‘simple’ and ‘complex’ remaining undefined, together with their associated operations (the only definitions being those implicit in Ded and in the expertise of Bornat and Thimbleby, or informal in their report). And finally, the heuristics were generated for a purpose, tried out for their adequacy (in the case of Ded) and then retained or discarded (for further application to Ded). This too is characteristic of a craft discipline. Accepting that Ded met its requirements for both functionality (enter text, review text, etc.) and for usability (use straight away, etc) – as claimed by Bornat and Thimbleby – it can be accepted as an example of good HCI craft practice.

To conclude this characterisation of HCI as a craft discipline, let us consider its potential for effectiveness. As earlier proposed (Section 2.3), an effective discipline is one whose practices successfully solve its general problem, whilst incurring acceptable costs in acquiring and applying the knowledge supporting those practices (see Dowell & Long [1988]). HCI as a craft discipline will be evaluated in general for its effectiveness in solving the general problem of designing humans and computers interacting, as exemplified by Bornat and Thimbleby’s development of Ded in particular.

Consideration of HCI as a craft discipline suggests that it fails to be effective (Dowell & Long [manuscript submitted for publication]). The first explanation of this – and one that may at first appear paradoxical – is that the (public) knowledge possessed by HCI as a craft discipline is not operational. That is to say, because it is either implicit or informal, it cannot be directly applied by those who are not associated with the generation of the heuristics or exposed to their use. If the heuristics are implicit in practice, they can be applied by others only by means of example practice. If the heuristics are informal, they can be applied only with the help of guidance from a successful practitioner (or by additional, but unvalidated, reasoning by the user). For example, the heuristic ”simple operations should be simple, and the complex possible’ could not be implemented without the help of Bornat and Thimbleby or extensive interpretation by the designer. The heuristic provides insufficient information for its operationalisation. In addition, since craft heuristics cannot be directly applied to practice, practice cannot be easily planned and coordinated. Further, when HF and SE design practice are allocated to different people or groups, practice cannot easily be integrated. (Bornat was responsible for both HF and SE design practice and was also final arbiter of design solutions.) Thus, with respect to the requirement for its knowledge to be operational, the HCI craft discipline fails to be effective.

If craft knowledge is not operational, then it is unlikely to be testable – for example, whether the ‘simple’ operations when implemented are indeed ‘simple’, and whether the ‘complex’ operations when implemented are indeed ‘possible’. Hence, the second reason why HCI as a craft discipline fails to be effective is because there is no guarantee that practice applying HCI craft knowledge will have the consequences intended (guarantees cannot be provided if testing is precluded). There is no guarantee that its application to designing humans and computers interacting will result in their performing work effectively. For example, the heuristic of providing rapid feedback in Ded does not guarantee that users know what they are doing, because they might not understand the contingencies of the feedback. (However, it would be expected to help understanding, at least to some extent, and more often than not). Thus, with respect to the guarantee that knowledge applied by practice will solve the general HCI problem, the HCI craft discipline fails to be effective.

If craft knowledge is not testable, then neither is it likely to be generalisable – for example, whether ‘simple’ operations that are simple when implemented in Ded are also ‘simple’ when implemented in a different text editor. Hence, the third explanation of the failure of HCI as a craft discipline to be effective arises from the absence of generality of its knowledge. To be clear, if being operational demands that (public) discipline knowledge can be directly applied by others than those who generated the knowledge, then being general demands that the knowledge be guaranteed to be appropriate in instances other than those in which it was generated. Yet, the knowledge possessed by HCI as a craft discipline applies only to those problems already addressed by its practice, that is, in the instances in which it was generated. Bornat and Thimbleby’s heuristics for solving the design problem of Ded may have succeeded in this instance, but the ability of the heuristics to support the solution of other design problems is unknown and, until a solution is attempted, unknowable. The suitability of the heuristics ‘ignore deficiencies of the terminal hardware’ and ‘undo one keystroke at a time’ for a system controlling the processes of a nuclear power plant could only be established by implementation and evaluation in the context of the power plant. In the absence of a well defined general scope for the problems to be addressed by the knowledge supporting HCI craft practice, each problem of designing humans and computers interacting has to be solved anew. Thus, with respect to the generality of its knowledge, the HCI craft discipline fails to be effective.

Further consideration of HCI as a craft discipline suggests that the costs incurred in generating, and so in acquiring craft knowledge, are few and acceptable. For example, Bornat and Thimbleby generated their design heuristics as required, that is – as evaluation showed the implementation of one heuristic to fail. Further, heuristics can be easily communicated (if not applied) and applied now (if applicable). Thus, with respect to the costs of acquiring its knowledge, HCI as a craft discipline would seem to be effective.

In summary, although the costs of acquiring its knowledge would appear acceptable, and although its knowledge when applied by practice sometimes successfully solves the general problem of designing humans and computers interacting to perform work effectively, the craft discipline of HCI is ineffective because it is generally unable to solve the general problem. It is ineffective because its knowledge is neither operational (except in practice itself), nor generalisable, nor guaranteed to achieve its intended effect – except as the continued success of its practice and its continued use by successful craftspeople.

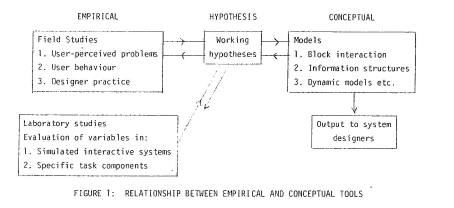

3.2. Conception of HCI as an Applied Science Discipline

The discipline of science uses scientific knowledge (in the form of theories, models, laws, truth propositions, hypotheses, etc.) to support the scientific practice (analytic, empirical, etc.) of solving the general problem of explaining and predicting the phenomena within its scope (structural, behavioural, etc.) (see Section 3.1). Science solves its general problem by hypothesis and test. Hypotheses may be based on deduction from theory or induction from regularities of structure or behaviour associated with the phenomena. Scientific knowledge is explicit and formal, operational, testable and generalisable. It is therefore refutable (if not proveable; Popper [1959]).

Scientific disciplines can be associated with both HF – for example, psychology, linguistics, artificial intelligence, etc. and SE – for example, computer science, artificial intelligence, etc. Psychology explains and predicts the phenomena of the mental life and behaviour of humans (for example, the acquisition of cognitive skill (Anderson [1983])); computer science explains, and predicts the phenomena of the computability of computers as Turing-compatible machines (for example, as concerns abstract data types (Scott [1976])).

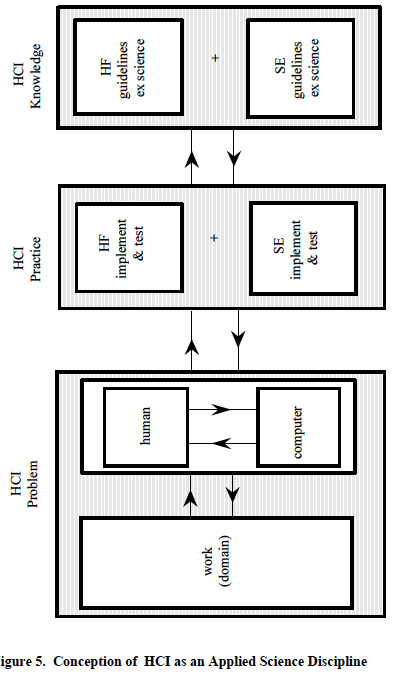

An applied science discipline is one which recruits scientific knowledge to the practice of solving its general problem – a design problem. HCI as an applied science discipline uses scientific knowledge as an aid to addressing the general problem of designing humans and computers interacting to perform work effectively. HCI as an applied science is represented schematically in Figure 5.

An example of psychological science knowledge which might be recruited to support the HF practice concerns the effect of feedback on sequences of behaviour, for example, noise and touch on keyboard operation, and confirmatory feedback on the sending of electronic messages (Hammond [1987]). (Feedback is chosen here because it was also used to exemplify craft discipline knowledge (see Section 3.1) and the contrast is informative.) Psychology provides the following predictive truth proposition concerning feedback: ‘controlled sequences need confirmatory feedback (both required and redundant); automated sequences only need required feedback during the automated sequence’. (The research supporting this predictive (but also explanatory proposition) would be expected to have defined and operationalised the terms – ‘feedback’, ‘controlled’, etc. and to have reported the empirical data on which the proposition is based.)

However, as it stands, the proposition cannot contribute to the solution of the HF design problem such as that posed by the development of the text-editor Ded (Bornat & Thimbleby [1989] – see Section 3.1). The proposition only predicts the modifications of behaviour sequences by feedback under a given set of conditions. It does not prescribe the feedback required by Ded to achieve effective performance of work (enter text, review it, etc.; to be usable straight away etc.).

Predictive psychological knowledge can be made prescriptive. For example Hammond transforms the predictive truth proposition concerning feedback into the following prescriptive proposition (or ‘guideline’): “When a procedure, task or sequence is not automatic to users (either because they are novice users or because the task is particularly complex or difficult), provide feedback in a number of complementary forms. Feedback should be provided both during the task sequence, to inform the user that things are progressing satisfactorily or otherwise, and at completion, to inform the user that the task sequence has been brought to a close satisfactorily or otherwise”.

However, although prescriptive, it is so with respect to the modifiability of sequences of behaviour and not with respect to the effective performance of work. Although application of the guideline might be expected to modify behaviour (for example, decrease errors and increase speed), there is no indication of how the modification (either in absolute terms, or relative to other forms of feedback or its absence) would ensure any particular desired effective performance of work. Nor can there be, since its prescriptive form has not been characterised, operationalised, tested, and generalised with respect to design for effective performance (but only the knowledge on which it is based with respect to behavioural phenomena).

As a result, the design of a system involving feedback, configured in the manner prescribed by the guideline, would still necessarily proceed by implementation, evaluation, and iteration. For example, although Bornat and Thimbleby appear not to have provided complementary feedback for the novice users of Ded, but only feedback by keypress (and not in addition on sequence completion – for example, at the end of editing a command), their users appear to have achieved the desired effective performance of work of entering text, using Ded straight away etc.

Computer science knowledge might similarly be recruited to support SE practice in solving the problem of designing computers interacting with humans to perform work effectively. For example, explanatory and predictive propositions concerning computability, complexity, etc. might be transformed into prescriptive propositions informing system implementation, perhaps in ways similar to the attempt to achieve ‘effective computability’ (Kapur & Srivs [1988]). Alternatively, predictive computer science propositions might support general prescriptive SE principles, such as modularity, abstraction, hiding, localization, uniformity, completeness, confirmability, etc. (Charette [1986]). These general principles might in turn be used to support specific principles to solve the SE design problem of computers interacting with humans.

However, as in the case of psychology, for as long as the general problem of computer science is the explanation and prediction of computability, and not the design of computers interacting with humans to perform work effectively, computer science knowledge cannot be prescriptive with respect to the latter. Whatever computer science knowledge (for example, use of abstract data types) or general SE principles (for example, modularity) informed or could have informed Bornat and Thimbleby’s development of Ded, the design would still have had to proceed by implementation, evaluation and iteration, because neither the computer science knowledge nor the SE principles address the problem of designing for the effective performance of work – entering text, using Ded straight away, etc.

To illustrate HCI as an applied science discipline more completely, there follows a detailed example taken from a case history reporting the design of a computer-aided learning system to induct new undergraduates into their field of study – cognitive psychology (Hammond & Allinson [1988]).

Hammond and Allinson called upon three areas of psychological knowledge, concerned with understanding and learning, to support the design of their system. These were ‘encoding specificity’ theory (Tulving [1972]), ‘schema’ theory (Mandler [1979]), and ‘depth of processing’ theory (Craik & Lockhart [1972]). Only the first will be used as an example here. ‘Encoding specificity’ and ‘encoding variability’ explain and predict peoples’ memory behaviours. ‘Encoding specificity’ asserts that material can be recalled if it contains distinctive retrieval cues that can be generated at the time of recall. ‘Encoding variability’ asserts that multiple exposure to the same material in different contexts results in easier recall, since the varied contexts will result in a greater number of potential retrieval cues.

On the basis of this psychological knowledge, Hammond and Allinson construct the guideline or principle: ‘provide distinctive and multiple forms of representation.’ They followed this prescription in their learning system by using the graphical and dynamic presentation of materials, working demonstrations and varied perspectives of the same information. However, although the guideline might have been expected to modify learning behaviour towards that of the easier recall of materials, the system design would have had to proceed by implementation, evaluation, and iteration. The theory of encoding specificity does not address the problem of the design of effective learning, in this case – new undergraduate induction, and the guideline has not been defined, operationalised, tested or generalised with respect to effective learning. Effective induction learning might follow from application of the guideline, but equally it might not (in spite of materials being recalled).

Although Hammond and Allinson do not report whether computer science knowledge was recruited to support the solution of the SE problem of designing the computer interacting with the undergraduates, nor whether general SE principles were recruited, the same conclusion would follow as for the use of psychological knowledge. Effective induction learning performance might follow from the application of notions such as effective computability, or of principles such as modularity, but equally it might not (in spite of the computer’s program being more computably effective and better structured).

In summary, the design of the undergraduate induction system by Hammond and Allinson illustrates the critical features of HCI as an applied science discipline. They addressed the specific form of the general problem (general because the knowledge and guidelines employed were intended to support a wide range of designs). Their practice involved the application of guidelines, the iterative implementation of the interacting computer and interacting human, and their evaluation. The implementation was supported by the use of psychological knowledge which formed the basis for the guidelines. The psychological knowledge (encoding specificity) was defined, operationalised, tested and generalised. The guideline ‘provide distinctive and multiple forms of representation’ was neither defined, operationalised, tested nor generalised with respect to effective learning performance.

Finally, consider the effectiveness of HCI as an applied science discipline. An evaluation suggests that many of the conclusions concerning HCI as a craft discipline also hold for HCI as an applied science discipline. First, its science knowledge cannot be applied directly, not – as in the case of craft knowledge – because it is implicit or informal, but because the knowledge is not prescriptive; it is only explanatory and predictive. Its scope is not that of the general problem of design. The theory of encoding specificity is not directly applicable.

Second, the guidelines based on the science knowledge, which are not predictive but prescriptive, are not defined, operationalised, tested or generalised with respect to desired effective performance. Their selection and application in any system would be a matter of heuristics (and so paradoxically of good practice). Even if the guideline of providing distinctive and multiple forms of representation worked in the case of undergraduate induction, it could not be generalised on the basis of this good practice alone.

Third, the application of guidelines based on science knowledge does not guarantee the consequences intended, that is effective performance. The provision of distinctive and multiple forms of representation may enhance learning behaviours, but not necessarily such as to achieve the effective undergraduate induction desired.

HCI as an applied science discipline, however, differs in two important respects from HCI as a craft discipline. Science knowledge is explicit and formal, and so supports reasoning about the derivation of guidelines, their solution and application (although one might have to be a discipline specialist so to do). Second, science knowledge (of encoding specificity, for example) would be expected to be more correct, coherent and complete than common sense knowledge concerning learning and memory behaviours.

Further, consideration of HCI as an applied science discipline suggests that the costs incurred in generating, and so in acquiring applied science knowledge, are both high (in acquiring science knowledge) and low (in generating guidelines). Whether the costs are acceptable depends on the extent to which the guidelines are effective. However, as indicated earlier, they are neither generalisable nor offer guarantees of effective performance.

In summary, although its knowledge when applied by practice in the form of guidelines sometimes solves the general problem of designing humans and computers interacting to perform work effectively, the applied science discipline is ultimately ineffective because it is generally unsuccessful in solving the general problem and its costs may be unacceptable. It fails to be effective principally because its knowledge is not directly applicable and because the guidelines based on its knowledge are neither generalisable, nor guaranteed to achieve their intended effect.

3.3. Conception of HCI as an Engineering Discipline

The discipline of engineering may characteristically solve its general problem (of design) by the specification of designs before their implementation. It is able to do so because of the prescriptive nature of its discipline knowledge supporting those practices – knowledge formulated as engineering principles. Further, its practices are characterised by their aim of ‘design for performance’. Engineering principles may enable designs to be prescriptively specified for artefacts, or systems which when implemented, demonstrate a prescribed and assured performance. And further, engineering disciplines may solve their general problem by exploiting a decompositional approach to design. Designs specified at a general level of description may be systematically decomposed until their specification is possible at a level of description of their complete implementation. Engineering principles may assure each level of specification as a representation of the previous level.

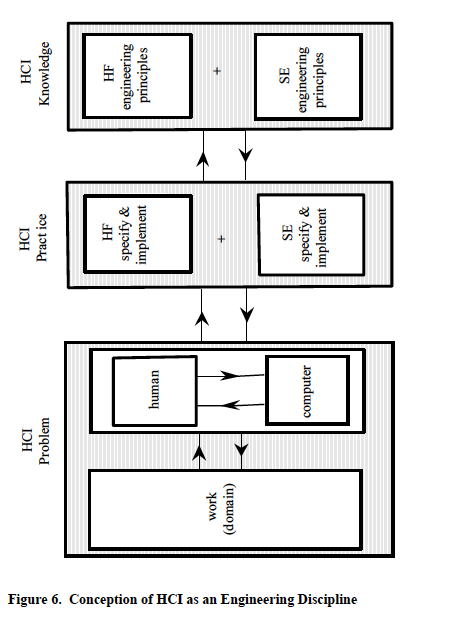

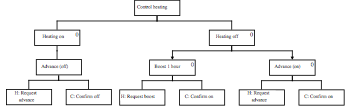

A conception of HCI as an engineering discipline is also apparent (for example: Dix & Harrison [1987]; Dowell & Long [manuscript submitted for publication]). It is a conception of HCI discipline knowledge as (ideally) constituted of (HF and SE) engineering principles, and its practices (HF and SE practices) as (ideally) specifying then implementing designs. This Section summarises the conception (schematically represented in Figure 6) and attempts to indicate the effectiveness of such a discipline.

The conception of HCI engineering principles assumes the possibility of a codified, general and testable formulation of HCI discipline knowledge which might be prescriptively applied to designing humans and computers interacting to perform work effectively. Such principles would be unequivocally formal and operational. Indeed their operational capability would derive directly from their formality, including the formality of their concepts – for example, the concepts of ‘simple’ and ‘complex’ would have an explicit and consistent definition (see Section 3.1).

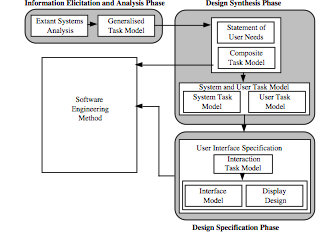

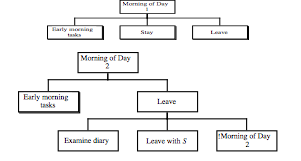

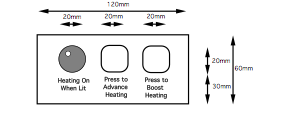

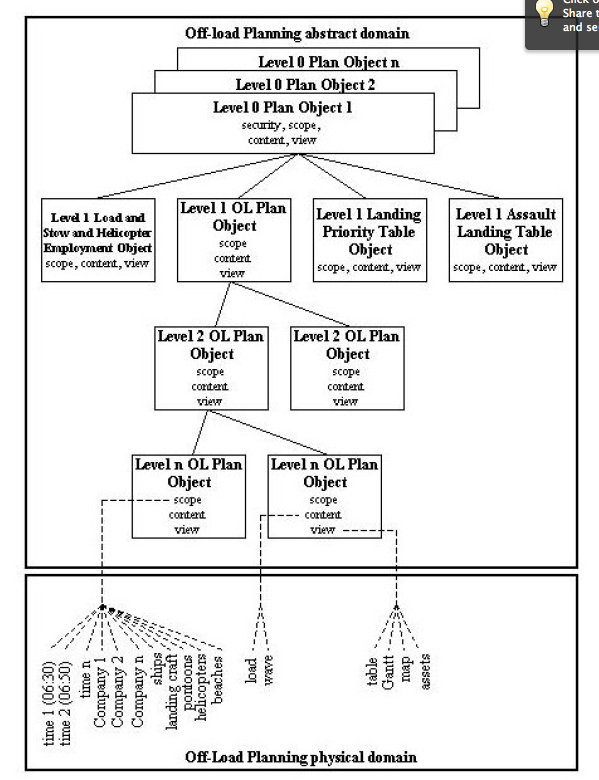

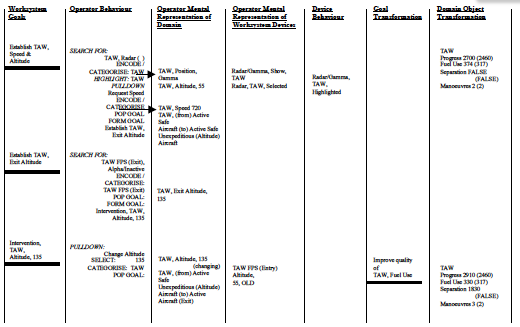

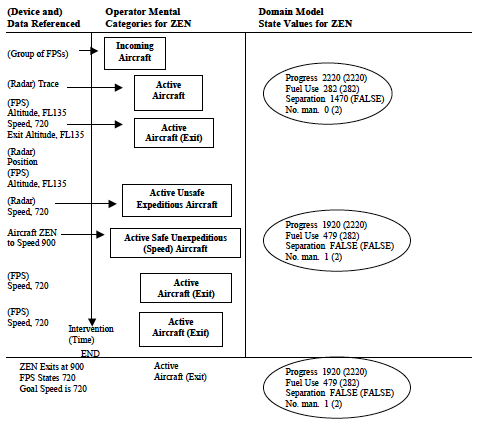

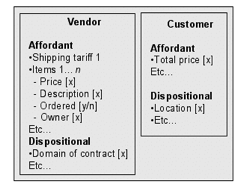

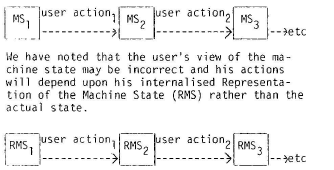

The complete and coherent definition of concepts, as necessary for the formulation of HCI engineering principles, would occur within a public and consensus conception of the general problem of HCI. A proposal for the form of such a conception (Dowell & Long [manuscript submitted for publication]), intended to promote the formulation of HCI engineering principles, can be summarised here. It dichotomises ‘interactive worksystems’ which perform work, and ‘domains of application’ in which work originates, is performed, and has its consequences. An interactive worksystem is conceptualised as the interacting behaviours of a human (the ‘user’) and a computer: it is a behavioural system. The user and computer constitute behavioural systems in their own right, and therefore sub-systems of the interactive worksystem. Behaviours are the trajectory of states of humans and computers in their execution of work. The behaviours of the interactive worksystem are reflexive with two independent structures, a human structure of the user and a hardware and software structure of the computer. The behaviours of the interactive worksystem are both physical and informational, and so also are its structures. Further, behaviour incurs a resource cost, distinguished as the ‘structural’ resource cost of establishing and maintaining the structure able to support behaviour, and the ‘behavioural’ resource cost of recruiting the structure to express behaviour.

The behaviours of an interactive worksystem intentionally effect, and so correspond with, transformations of objects. Objects are physical and abstract and exhibit the affordance for transformations arising from the state potential of their attributes. A domain of application is a class of transformation afforded by a class of objects. An organisations` requirements for specific transformations of objects are expressed as product goals; they motivate the behaviours of an interactive worksystem.

The effectiveness of an interactive worksystem is expressed in the concept of performance. Performance assimilates concepts expressing the transformation of objects with regard to its satisfying a product goal, and concepts expressing the resource costs incurred in realising that transformation. Hence, performance relates an interactive worksystem with a domain of application. A desired performance may be specified for any worksystem attempting to satisfy a particular product goal.

The concepts described enable the expression of the general problem addressed by an engineering discipline of HCI as: specify then implement user behaviour {U} and computer behaviour {C}, such that {U} interacting with {C} constitutes an interactive worksystem exhibiting desired performance (PD). It is implicit in this expression that the specification of behaviour supposes and enables specification of the structure supporting that behaviour. HCI engineering principles are conceptualised as supporting the practices of an engineering HCI discipline in specifying implementable designs for the interacting behaviours of both the user and computer that would achieve PD.

This conception of the general problem of an engineering discipline of HCI supposes its further decomposition into two related general problems of different particular scopes. One problem engenders the discipline of HF, the other the discipline of SE; both disciplines being incorporated in HCI. The problem engendering the discipline of SE is expressed as: specify then implement {C}, such that {C} interacting with {U} constitutes an interactive worksystem exhibiting PD. The problem engendering the discipline of HF is expressed as: specify then implement {U}, such that {U} interacting with {C} constitutes an interactive worksystem exhibiting PD.

The disciplines of SE and HF might each possess their own principles. The abstracted form of those principles is visible. An HF engineering principle would take as input a performance requirement of the interactive worksystem, and a specified behaviour of the computer, and prescribe the necessary interacting behaviour of the user. An SE engineering principle would take as input the performance requirement of the interactive worksystem, and a specified behaviour of the user, and prescribe the necessary interacting behaviour of the computer.

Given the independence of their principles, the engineering disciplines of SE and HF might each pursue their own practices, having commensurate and integrated roles in the development of interactive worksystems. Whilst SE specified and implemented the interacting behaviours of computers, HF would specify and implement the interacting behaviours of users. Together, the practices of SE and HF would aim to produce interactive worksystems which achieved PD.

It is the case, however, that the contemporary discipline of HF does not possess engineering principles of this idealised form. Dowell & Long [manuscript submitted for publication) have postulated the form of potential HF engineering principles for application to the training of designers interacting with particular visualisation techniques of CAD systems. A visualisation technique is a graphical representational form within which images of artefacts are displayed; for example, the 21/2 D wireframe representational form of the Necker cube. The supposed principle would prescribe the visual search strategy {u} of the designer interacting with a specified display behaviour {c} of the computer (supported by a specified visualisation technique) to achieve a desired performance in the ‘benchmark’ evaluation of a design.

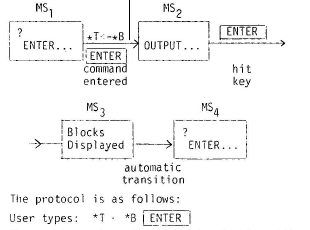

Neither does the contemporary discipline of SE possess engineering principles of the idealised form discussed. However, formal models of the interaction of display editors proposed by Dix and Harrison [1987] may show potential for development in this respect. For example, Dix and Harrison model the (behavioural) property of a command that is ‘passive’, a command having no effect on the ‘data’ component of the computer’s state. Defining a projection from state into result as r: SR, a passive command c has the property that r(s) = r(c(s)). Although the model has a formal expression, the user behaviour interacting with the (passive) computer behaviour is only implied, and the model makes no reference to desired performance.

It is likely the case, however, that some would claim the (idealised) conception of HCI as an engineering discipline to be unrealiseable. They might justify their objection by claiming the general problem of HCI to be ‘too soft’ to allow the development of engineering principles – that human behaviour is too indeterministic (too unspecifiable) to be subject to such principles. Yet human behaviour can be usefully deterministic to some degree – as demonstrated, for example, by the response of driver behaviour to traffic system protocols. There may well be at least a commensurate potential for the development of HCI engineering principles.

To conclude this summary description of the conception of an engineering discipline of HCI, we might consider the potential effectiveness of such a discipline. As before, effectiveness is evaluated as the success with which the discipline might solve its general problem, and the costs incurred with regard to both the acquisition and application of knowledge.

First, HCI engineering principles would be a generaliseable knowledge. Hence, application of principles to solving each new design problem could be direct and efficient with regard to costs incurred. The discipline would be effective. Second, engineering HCI principles would be operational, and so their application would be specifiable. The further consequence of this would be that the roles of HF and SE in Systems Development could be specified and integrated, providing better planned and executed development programmes. The minimisation of application costs would result in an effective discipline. Third, engineering principles would have a guaranteed efficacy. Because they would be operational, they would be testable and their reliability and generality could be specified. Their consequent assurance of product quality would render effective an engineering discipline of HCI.

Finally, consideration of HCI as an engineering discipline suggests that the costs of formulating engineering principles would be severe. A research programme committed to formulating even a basic corpus of HCI engineering principles might only be conceived as a long-term endeavour of extreme scale.

In summary, although the costs of their formulation would be severe, the potential of a corpus of engineering principles for improving product quality is large, and so also might be the potential for effectiveness of an engineering discipline of HCI.

4. Summary and Conclusions

This paper has developed the Conference theme of ‘the theory and practice of HCI’. Generalisation of the theme, in terms of a framework for conceptions of the HCI discipline, has shown that in addition to theory and practice, the theme needs to explicitly reference the general problem addressed by the discipline of HCI and the scope of the general problem.

The proposal made here is that the general problem of HCI is the design of humans and computers interacting to perform work effectively. The qualification of the general problem as ‘design’, and the addition to the scope of that problem of ‘…. to perform work effectively’, has important consequences for the different conceptions of HCI (see Section 3). For example, since design is not the general problem of science, scientific knowledge (for example, psychology or computer science) cannot be recruited directly to the practice of solving the general problem of design (see Barnard, Grudin & Maclean [1989]). Further, certain attempts to develop complete engineering principles for HCI fail to qualify as such, because they make no reference to ‘…. to perform work effectively’ (Dix & Harrison [1987]; Thimbleby [1984]).

Development of the theme indicated there might be no singular conception of the discipline of HCI. Although all conceptions of HCI as a discipline necessarily include the notion of practice (albeit of different types), the concept of theory is more readily associated with HCI as an applied science discipline, because scientific knowledge in its most correct, coherent and complete form is typically expressed as theories. Craft knowledge is more typically expressed as heuristics. Engineering knowledge is more typically expressed as principles. If HCI knowledge is limited to theory, and theory is presumed to be that of science, then other conceptions of HCI as a discipline are excluded (for example, Dowell & Long [manuscript submitted for publication]).

Finally, generalisation of the Conference theme has identified two conceptions of HCI as a discipline as alternatives to the applied science conception implied by the theme. The other two conceptions are HCI as a craft discipline and HCI as an engineering discipline. Although all three conceptions address the general problem of HCI, they differ concerning the knowledge recruited to solve the problem. Craft recruits heuristics; applied science recruits theories expressed as guidelines; and engineering recruits principles. They also differ in the practice they espouse to solve the general problem. Craft typically implements, evaluates and iterates (Bornat & Thimbleby [1989]); applied science typically selects guidelines to inform implementation, evaluation and iteration (although guidelines may also be generated on the basis of extant knowledge, e.g. – Hammond & Allinson [1988]); and engineering typically would specify and then implement (Dowell & Long [1988]).

The different types of knowledge and the different types of practice have important consequences for the effectiveness of any discipline of HCI. Heuristics are easy to generate, but offer no guarantee that the design solution will exhibit the properties of performance desired. Scientific theories are difficult and costly to generate, and the guidelines derived from them (like heuristics) offer no final guarantee concerning performance. Engineering principles would offer guarantees, but are predicted to be difficult, costly and slow to develop.

The development of the theme and the expression of the conceptions of HCI as a discipline – as craft, applied science and engineering – can usefully be employed to explicate issues raised by, and of concern to, the HCI community. Thus, Landauer’s complaint (Landauer [1987a]) that psychologists have not brought to HCI an impressive tool kit of design methods or principles can be understood as resulting from the disjunction between psychological principles explaining and predicting phenomena, and prescriptive design principles required to guarantee effective performance of work (see Section 3.2). Since research has primarily been directed at establishing the psychological principles, and not at validating the design guidelines, then the absence of an impressive tool kit of design methods or principles is perhaps not so surprising.

A further issue which can be explained concerns the relationship between HF and SE during system development. In particular, there is a complaint by SE that the contributions of HF to system development are ‘too little’, too late’ and unemployable (Walsh, Lim, Long, & Carver [1988]). Assuming HCI to be an applied science discipline, HF contributions are too little because psychology does not address the general problem of design and so fails to provide a set of principles for the solution of that problem. HF contributions are too late, because they consist largely of evaluations of designs already implemented, but without the benefit of HF. They are unemployable, because they were never specified, and because implemented designs can be difficult, if not impossible, and costly to modify. Within an HCI engineering discipline, HF contributions would be adequate (because within the scope of the discipline’s problem); on time (because specifiable); and implementable (because specified). Landauer’s plea (Landauer [1987b]) that HF should extend its practice from implementation evaluation to user requirements identification and the creation of designs to satisfy those requirements can be similarly explicated.

Lastly, Carroll and Campbell’s claim (Carroll & Campbell [1988]) that HCI research has been more successful at developing methodology than theory can be explicated by the need for guidelines to express psychological knowledge and the need to validate those guidelines formally, and the absence of engineering principles, plus the importation of psychology research methods into HCI and the simulation of good (craft) practice. The methodologies, however, are not methodological principles which guarantee the solution of the design problem (Dowell & Long [manuscript submitted for publication]), but procedures to be tailored anew in the manner of a craft discipline. Thus, relating the conceptions of HCI as a set of possible disciplines provides insight into whether HCI research has been more successful at developing methodologies than theories.

In addition to explicating issues already formulated, the development of the Conference theme and the expression of the conceptions of HCI as a discipline raise two novel issues. The first concerns reflexivity both with respect to the general design problem and with respect to the creation of discipline knowledge. It is often assumed that only HCI as an applied scientific discipline (by means of guidelines) and as an engineering discipline (by means of principles) are reflexive with respect to the general design problem. The conception of HCI as a craft discipline, however, has shown that it is similarly reflexive – by means of heuristics. Concerning the creation of discipline knowledge, it is often assumed that only the solution of the general discipline problem requires the reflexive cognitive act – of reason and intuition concerning the objects of activity (Kant [1781]). However, the conceptions of HCI as a craft discipline, as an applied science discipline, and as an engineering discipline suggest that the intial creation of discipline knowledge, whether heuristics, guidelines or principles, in all cases requires a reflexive cognitive act involving intuition and reason. Thus, contrary to common assumption, the craft, applied science, and engineering conceptions of the discipline of HCI are similarly reflexive with regard to the general design problem. The intial generation of albeit different discipline knowledges requires in each case the reflexive cognitive act of reason and intuition.

The second novel issue raised by the development of the Conference theme and the conceptions of HCI as a discipline is the relationship between the different conceptions. For example, the different conceptions of HCI and their associated paradigm activities might be considered to be mutually exclusive and uninformative, one with respect to the other. Alternatively, one conception and its associated activities might be considered to be mutually supportive with respect to another. For example, engineering principles might be developed bottom-up on the basis of inductions from good craft practice. Alternatively, engineering principles might be developed top-down on the basis of deductions from scientific theory – both from psychology and from computer science. It would be possible to advance a rationale justifying either mutual exclusion of conceptions or mutual support. The case for mutual exclusion would be based on the fact that the form of their knowledge and practice differs, and so one conception would be unable directly to inform another. For example, craft practice will not develop a theory which can be directly assimilated to science; science will not develop design principles which can be directly recruited to engineering. Thus, the case for mutual exclusion is strong.

However, there is a case for mutual support of conceptions and it is presented here as a final conclusion. The case is based on the claim made earlier that the creation of discipline knowledge of each conception of HCI requires a reflexive cognitive act of reason and intuition. If the claim is accepted, the reflexive cognitive act of one conception might be usefully but indirectly informed by the discipline knowledge of another. For example, the design ideas, or heuristics, which formed part of the craft practice of Bornat and Thimbleby in the 1970s (Bornat & Thimbleby [1989]), undoubtedly contributed to Thimbleby’s more systematic formulation (Thimbleby [1984]) and the formal expression by Dix and Harrison (Dix & Harrison [1987]). Although the principles fail to address the effectiveness of work and so fail to qualify as HCI engineering principles, their development towards that end might be encouraged by mutual support from engineering conceptions of HCI. Likewise, scientific concepts such as compatibility (Long [1987]) may indirectly inform the development of principles relating users’ mental structures to the analytic structure of a domain of application (Long [1989]), and even provide an indirect rationalisation for the concepts themselves and their relations with other associated concepts. Mutual support of conceptions, as opposed to mutual exclusion, has two further advantages. First, it maximises the exploitation of what is known and practised in HCI. The current success of HCI is not such that it can afford to ignore potential contributions to its own advancement. Second, it encourages the notion of a community of HCI superordinate to that of any single discipline conception. The novelty and complexity of the enterprise of developing knowledge to support the solution of the general problem of designing humans and computers interacting to perform work effectively requires every encouragement for the establishment and maintenance of such a community. Thus, the mutual support of different conceptions of HCI as a discipline is recommended.

References

J R Anderson [1983], The Architecture of Cognition, Harvard

University, Cambridge MA.

P Barnard, J Grudin & A Maclean [1989], “Developing a Science Base for the Naming of Computer Commands”, in Cognitive Ergonomics and Human Computer Interaction, J B Long & A D Whitefield, eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

R Bornat & H Thimbleby [1989], “The Life and Times of Ded, Text Display editor”, in Cognitive Ergonomics and Human Computer Interaction, J B Long & A D Whitefield, eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

P Buckley [1989], “Expressing Research Findings to have a Practical Influence on Design”, in Cognitive Ergonomics and Human Computer Interaction, J B Long & A D Whitefield, eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

J M Carroll & R L Campbell [1988], “Artifacts as Psychological Theories: the Case of Human Computer Interaction”, IBM research report, RC 13454(60225) 1/26/88, T.J. Watson Research Division Center, Yorktown Heights, NY. 10598.

R N Charette [1986], Software Engineering Environments, Intertexts Publishers/McGraw Hill, New York.

F I M Craik & R S Lockhart [1972], “Levels of Processing: A Framework for Memory Research”, Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behaviour, 11, 671-684.

A J Dix & M D Harrison [1987], “Formalising Models of Interaction in the Design of a Display Editor”, in Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT’87, H J Bullinger & B Shackel, (ed.s), North-Holland, Amsterdam, 409-414.

J Dowell & J B Long [1988], “Human-Computer Interaction Engineering”, in Designing End-User Interfaces, N Heaton & M Sinclair, eds., Pergamon Infotech, Oxford.

J Dowell & J B Long, “Towards a Conception for an Engineering Discipline of Human Factors”, (manuscript submitted for publication).

P Gilligan & J B Long [1984], “Videotext Technology: an Overview with Special Reference to Transaction Processing as an Interactive Service”, Behaviour and Information Technology, 3, 41-47.

N Hammond & L Allinson [1988], “Development and Evaluation of a CAL System for Non-Formal Domains: the Hitchhiker`s Guide to Cognition”, Computer Education, 12, 215-220.

N Hammond [1987], “Principles from the Psychology of Skill Acquisition”, in Applying Cognitive Psychology to User-Interface Design, M Gardiner & B Christie, eds., John Wiley and Sons, Chichester.

I Kant [1781], The Critique of Pure Reason, Second Edition, translated by Max Muller, Macmillan, London.

D Kapur & M Srivas [1988], “Computability and Implementability: Issues in Abstract Data Types,” Science of Computer Programming, Vol. 10.

T K Landauer [1987a], “Relations Between Cognitive Psychology and Computer System Design”, in Interfacing Thought: Cognitive Aspects of Human-Computer Interaction, J M Carroll, (ed.), MIT Press, Cambridge MA. 23

T K Landauer [1987b], “Psychology as Mother of Invention”, CHI SI. ACM-0-89791-213-6/84/0004/0333

J B Long [1989], “Cognitive Ergonomics and Human Computer Interaction: an Introduction”, in Cognitive Ergonomics and Human Computer Interaction, J B Long & A D Whitefield, eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

J Long [1987], “Cognitive Ergonomics and Human Computer Interaction”, in Psychology at Work, P Warr, eds., Penguin, England.

J M Mandler [1979], “Categorical and Schematic Organisation in Memory”, in Memory Organisation and Structure, C R Puff, ed., Academic Press, New York.

H H Pattee [1973], Hierarchy Theory: the Challenge of Complex Systems, Braziller, New York.

K R Popper [1959], The Logic of Scientific Discovery, Hutchinson, London.

D Scott [1976], “Logic and Programming”, Communications of ACM, 20, 634-641.

H Thimbleby [1984], “Generative User Engineering Principles for User Interface Design”, in Proceedings of the First IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT’84. Vol.2, B Shackel, ed., Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, 102-107.

E Tulving [1972], “Episodic and Semantic Memory”, in Organisation of Memory, E Tulving & N Donaldson, eds., Academic Press, New York.

P Walsh, K Y Lim, J B Long & M K Carver [1988], “Integrating Human Factors with System Development”, in Designing End-User Interfaces, N Heaton & M Sinclair, eds., Pergamon Infotech, Oxford.

Acknowledgement. This paper has greatly benefited from discussion with others and from their criticisms. In particular, we would like to thank: Andy Whitefield and Andrew Life, colleagues at the Ergonomics Unit, University College London; Charles Brennan of Cambridge University, and Michael Harrison of York University; and also those who attended a seminar presentation of many of these ideas at the MRC Applied Psychology Unit, Cambridge. The views expressed in the paper, however, are those of the authors.